FDA’s approval of an Ebola vaccine can serve as a framework for drug development during other epidemics.

The world’s second largest Ebola outbreak is currently affecting the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In the 17 months since the outbreak started, over 3,400 people have contracted the disease and 66 percent of those infected have died.

But the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved a vaccine that could contain the current outbreak and be used as a model for approving drugs during a future public health emergency.

In December, FDA announced its approval of Ervebo—a vaccine used to prevent one of the most common strains of the Ebola virus disease. The drug was approved as a single injection for adults over the age of 18 years old. FDA made the announcement one month after the European Commission authorized the vaccine to be marketed in the European Union.

In a press release announcing FDA approval, the director of the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Peter Marks, explained that the research methods were “precedent-setting” and can help the agency and public health officials create a new framework for future epidemics. The agency relied on studies conducted during prior Ebola outbreaks, cooperation with the private sector, and special approval pathways to approve the vaccine.

Although Ebola is very rare in the United States, FDA approval will allow military personnel and public health workers to be vaccinated before traveling to areas commonly affected by the disease. The vaccine will also likely be stockpiled to prevent a future outbreak or bioterrorism threat within the United States.

Scholars have suggested that FDA’s approval also holds international significance. Regulators in countries affected by Ebola outbreaks may decide to expedite their approval processes for the vaccine because they know that data have already been reviewed and approved by FDA.

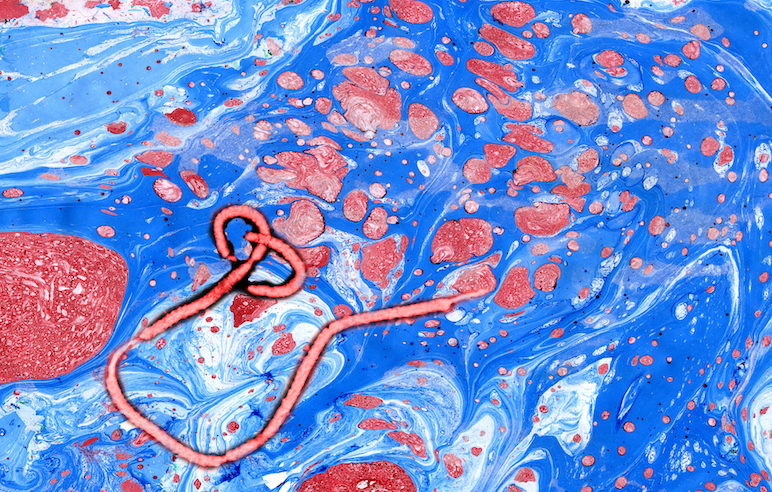

Quick approval and access to the vaccine can be key to stopping Ebola epidemics. The disease spreads rapidly after contact with blood or other bodily fluids from an infected individual. Once a patient contracts the disease, it is often deadly. Ebola has an average mortality rate of 50 percent and presently there exists no FDA-approved treatment—although there are investigational therapeutics under development.

In 2014, Ebola spread throughout Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, creating the largest and most deadly outbreak of the disease. The epidemic, however, prompted FDA to cooperate with the pharmaceutical industry. The agency used incentives to entice manufacturers to develop a vaccine even though it was less profitable than other drugs.

FDA awarded the manufacturer of Ervebo a tropical disease priority review voucher, allowing the pharmaceutical company to accelerate approval for another drug that would not otherwise qualify for priority review. When the company decides to use the voucher, the drug of its choice will be reviewed in about six months instead of the typical ten months, allowing the chosen product to get to the market faster. Alternatively, the company can sell the voucher to another manufacturer—an approach which has proven to be lucrative. Vouchers can reportedly sell for over $300 million.

FDA also gave Ervebo priority review and breakthrough therapy designation to expedite the drug development and approval process for the Ebola vaccine itself. These classifications allowed the vaccine to be studied quickly so it could become available during the ongoing Ebola outbreak.

Many of the studies FDA reviewed involved coordination with international agencies and research conducted outside of the United States. For example, FDA stated that the agency relied on a study conducted in Guinea during the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Researchers gave the vaccine to people who may have been exposed to Ebola to determine the effectiveness of the drug. FDA said the study showed that the vaccine was up to 100 percent effective when it was administered soon after the suspected exposure.

The safety of Ervebo was also tested in Africa, Europe, and North America, according to FDA. These studies involved cooperation between FDA, international regulators, and the World Health Organization (WHO).

WHO also played a key role in handling ethical concerns about testing the vaccine on human subjects during a public health emergency. During the 2014 epidemic, potential vaccines and investigational treatments started to show promise in animal studies, although most had not yet been shown to be effective or safe for humans. But WHO’s advisory panel unanimously concluded that, given the public health emergency, it was ethical to use investigational drugs and conduct clinical trials in areas affected by the outbreak.

FDA recognized the importance that these clinical studies played and cited two of the trials as direct evidence supporting the vaccine’s approval.

Alex Azar, the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, acknowledged the significance of FDA’s approval and suggested that the vaccine is already being used in Democratic Republic of the Congo to curb the current outbreak. Azar stated that the U.S. government will continue cooperating with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, WHO, and governments in other regions affected by Ebola.

FDA has also indicated that it will continue to use innovative techniques to accelerate the approval pathway for products that can help prevent, diagnose, and treat future Ebola outbreaks. FDA recognizes that the vaccine approval is “a critical milestone in public health preparedness and response,” but also seeks to continue preparing for and responding to public health emergencies both within the United States and abroad.