Scholars discuss how to best regulate addictive online platforms.

Nearly one-third of U.S. adults report being online “almost constantly.” Some consumer advocates argue that this behavior may be more of a compulsion than a choice. They also allege that this compulsion is by design: Big Tech companies profit from capturing and selling consumer attention, commentators point out.

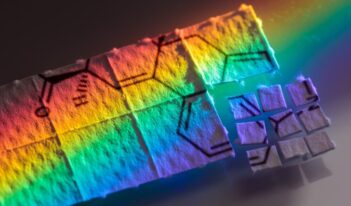

Health experts warn that manipulative technology—technology designed to capture and profit from human attention—can affect brain chemistry in ways similar to drug use and gambling addiction.

Addiction specialists explain that when individuals get a dopamine jolt—for example, after seeing a notification on their phones—their brains respond by releasing serotonin, a hormone that makes them feel happy. The more dopamine individuals get, however, the more they want it.

Eventually, going without the dopamine trigger leads to a rise in the stress hormone cortisol, experts explain. The addicted user feels as if the only way to ease this stress is to continue checking their device for more notifications.

Consumer advocates argue that Big Tech companies, including Meta, Alphabet, and Amazon, construct their platforms to exploit these chemical processes in the brain. These advocates emphasize that companies design their products to hook users with addictive features such as infinite scroll, algorithmic personalization, and push notifications. The longer a user engages with the platform, the more data a company collects about that user, which it can then sell to advertisers, advocates explain.

Commentators emphasize that the stakes of technology addiction are high, affecting mental health, attention span, and even political radicalization.

Much of the debate around manipulative technology has centered on youth. In 2023, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy released an advisory cautioning that social media poses risks of harm to children’s mental health. Later that year, 41 states and the District of Columbia sued Meta—the parent company of Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp—claiming that the company designed its platforms to addict children.

Federal lawmakers have proposed bills aimed at protecting young consumers from manipulative technology. In the absence of federal protections, some states have begun legislating to protect youth.

Democratic lawmakers in New York, for example, have proposed laws that would bar social media companies from employing addictive algorithms on youth accounts without parental consent. Utah passed and amended similar laws this year. Florida passed a social media age-restriction law recently that the state’s House Speaker reportedly said would limit “the addictive features that are at the heart of why children stay on these platforms for hours and hours on end.”

Opponents of such regulations argue that requiring identity verification and parental consent restricts the ability of marginalized young people—including immigrants and LGBTQ youth—to access information. Critics also argue that these laws may violate the First Amendment rights of users to access lawful speech online. Some federal courts have agreed, blocking similar laws in Arkansas and California on free speech grounds.

In this week’s Saturday Seminar, scholars discuss how best to regulate addictive technology.

- Lawmakers should apply financial sector regulation principles to Big Tech, Caleb N. Griffin of the University of Arkansas School of Law proposes in an article in Cornell Law Review. Griffin argues that regulators should designate addictive online technology as “systematically important platforms.” The proposed designation would be similar to “SIFIs” in the financial sector, which are financial institutions subject to strict regulations by virtue of their importance to society. Such a designation would permit regulators to impose special rules on tech companies with the goal of limiting manipulative practices, Griffin suggests. He argues that companies with this designation would be required to provide users with options to disable or consent to manipulative features.

- In an article in the North Carolina Law Review, James Niels Rosenquist of Massachusetts General Hospital, Fiona M. Scott Morton of the Yale School of Management, and Samuel N. Weinstein of Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law argue that the addictive features of tech platforms should raise concerns for antitrust enforcers. Rosenquist, Morton, and Weinstein contend that large tech platforms do not face adequate competitive pressure to encourage the minimization of unsafe practices. They suggest that if consumers had more choice in which platforms to use, platforms would be compelled to increase the safety of their products to attract users. To facilitate competition, the Morton team argues that antitrust enforcers should consider the addictiveness of goods in their enforcement priorities.

- In an article in the Journal of Free Speech Law, Matthew B. Lawrence of Emory University School of Law examines the intersection of “addictive design” by social media companies and the legislative efforts to regulate them. Lawrence notes the legal challenges posed by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act and the First Amendment and explores this tension from two paradigms: the public health regulatory paradigm and the internet regulatory paradigm. He argues that although broad federal preemption and free speech concerns may make courts skeptical of state efforts to regulate addictive design, they should not allow these platforms to become zones free from public health law. Lawrence suggests that courts find a middle ground that allows some state regulation of addictive design without completely barring content moderation or free expression.

- Regulators should use product liability principles to prioritize user safety from the harms posed by social media platforms, argues Matthew P. Bergman of Lewis & Clark Law School in an article in the Lewis & Clark Law Review. Accountability under product liability law, he suggests, could force social media platforms to internalize the costs of safety, leading to healthier design choices. Bergman contends that the “deliberate design decisions” of these platforms, aimed at maximizing user engagement, have a negative impact on youth mental health. Through a product liability approach, Bergman recommends amending Section 230 to better reflect the realities of widespread social media use and its effects on public health and safety.

- In an article in the Roger Williams University Law Review, John J. Chung of Roger Williams University School of Law argues that gaming laws should not apply to “loot boxes” that video gamers may purchase to enhance their outcomes. Critics claim that loot boxes induce gambling behaviors because the contents of the boxes are unknown at the time of purchase. Nevertheless, Chung maintains that loot boxes cannot be governed by gaming laws because they only have value in the virtual world of video games. He argues that loot boxes do not contain a prize of real, monetary value—a required element in the definition of “unlawful gambling.” Instead, Chung suggests that a solution to their addictive qualities might be found in consumer protection law.

- In a Wisconsin Law Review article, Gaia Bernstein of Seton Hall Law School contends that the COVID-19 pandemic increased awareness of the harms of overusing technology. Bernstein identifies factors that can influence windows of opportunity to regulate new technologies, such as the historical tendency of federal regulators not to intervene early when new technologies emerge. She also highlights the “technological invisibility” of product designs that prevent users from understanding their screen time fully. Bernstein concludes that although the COVID-19 pandemic compelled people to mediate nearly every aspect of their lives through screens, the pandemic also created a new window of opportunity to seek a better balance between online and offline pursuits.