Republican legislation would require Congress to approve major rules passed by federal agencies.

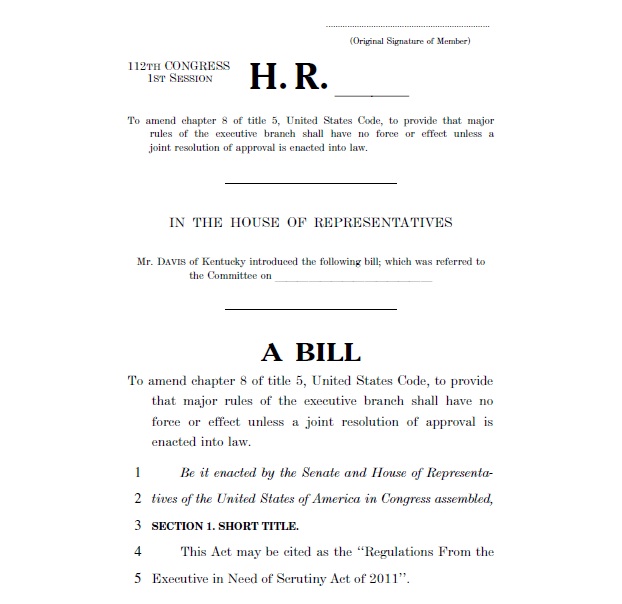

As part of Congressional Republicans’ agenda outlined in their Pledge to America, Representative Geoff Davis (R-KY) has reintroduced the REINS Act (H.R. 10).

Under the REINS Act – which stands for Regulations from the Executiver In Need of Scrutiny — federal agencies would need to submit their final rules to each House of Congress and to the Comptroller General before they could take effect. These transmittals to Congress would need to be accompanied by a report containing a copy of the rule, a concise general statement relating to the rule, any agency cost-benefit analysis of the rule, an analysis of any related regulatory actions, and a classification of the rule as “major” or “non-major.” Major rules would include those that would have an economic effect of over $100 million per year.

In order for a major rule to take legal effect, Congress would need to act explicitly to approve it by joint resolution within 70 session days of the rule’s submission. By contrast, non-major rules would be deemed final simply upon their transmittal to Congress, although the bill allows for Congress to disapprove of these rules within 60 days.

To assist Congress in considering major rules in a timely manner, the REINS Act would require House and Senate leaders to introduce a joint resolution of approval within 3 days of a federal agency’s rule submission. Legislative committees would then have 15 days to consider the resolution before it would be automatically discharged to the floor for consideration. Debates would be limited to no more than two hours; motions to postpone and amendments to the rule would be prohibited. Each House would then need to vote on final passage of the resolution within 15 days of the committees’ report or discharge.

The REINS Act purports to address concerns that federal regulations impose significant costs on society without sufficient congressional oversight. The U.S. Small Business Administration estimates that regulations impose more than $1.1 trillion in annual costs on businesses. Supporters of the REINS Act claim that the bill will promote transparency and accountability by requiring Congress to take greater responsibility for regulatory costs.

Critics of the bill argue that regulations also deliver substantial offsetting benefits and that the REINS Act would hamper agencies’ ability to implement beneficial regulations. Considering that agencies promulgated 94 “major” rules in 2010, critics also doubt whether Congress will have the time to review these regulations and vote for their approval.

According to Sally Katzen of the Podesta Group, a government relations firm, the REINS Act may also violate constitutional principles of separation of powers. In testimony before the House Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Courts, Commercial and Administrative Law, Katzen has argued that by requiring both houses to approve a regulation, the bill would contravene INS v. Chadha, which prohibits a one-house legislative veto of agency actions. She also argued that, under Morrison v. Olson, a statute “is suspect if it ‘involves an attempt by Congress to increase its own powers at the expense of the executive branch.’”

Writing in a blog, The Volokh Conspiracy, Professor Jonathan Adler of Case Western Reserve University School of Law has responded that constitutional attacks on the REINS Act stem from a “fundamental confusion about the nature of executive power.” Adler argues that the core function of the executive branch is to prosecute and investigate, not to legislate. Thus, when Congress restrains the executive’s power to legislate, it is merely taking back power it has delegated, not constraining the executive’s fundamental powers.

Adler also suggests that the REINS Act may help promote exactly the kind of bicameral congressional responsibility that the Chadha Court wanted to cultivate. The bill would ensure that consequential federal rules would take legal effect not merely if an agency says they should, but rather only if bicameralism and presentment procedures are followed.

The REINS Act currently has 127 co-sponsors in the House. Senator Paul Rand (R-KY) has introduced a companion bill in the Senate which currently has 25 cosponsors. In the months ahead, the REINS Act seems certain to generate considerable debate among the members of the 112th Congress.