Allegations in complaints befit a conspiracy novel – one that Apple argues is completely fictional.

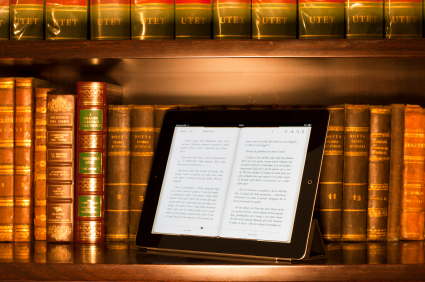

The Department of Justice Antitrust Division’s recent complaint against Apple Inc. and five major domestic book publishers is so compelling that you could easily imagine it becoming a bestselling e-book itself.

As reported widely, the Justice Department has charged Apple and the publishers with unlawfully conspiring to raise the price of e-books. The government’s complaint reads somewhat like a Scott Turow novel involving several allegedly conspiratorial dinner meetings between publisher CEOs at exclusive Manhattan restaurants. This is not without irony since Turow, in his capacity as president of the Authors Guild, recently wrote an open letter calling the government’s antitrust action “grim news for everyone who cherishes a rich literary culture.”

Be that as it may, the federal government’s 36-page complaint, along with separate complaints by state attorneys general and private class action litigants, alleges a conspiracy worthy of Turow. According to the federal government, starting in late 2009 Apple served as the hub, and the publishers as the spokes, in a plot to thwart competition from Amazon – which at the time sold 9 out of every 10 e-books on the market and was known to price aggressively – and to raise prices to e-book consumers overall. Apparently the plot was successful. The state attorneys general allege that the resulting e-book consumer overcharge amounted to “substantially more than one hundred million dollars.”

According to the Justice Department complaint, the terms of the alleged conspiracy were negotiated between the publishers and Apple during the lead up to the Apple iPad launch in early 2010. The complaint alleges that the conspiracy is documented in the e-book distribution agreements between Apple and the publishers, the terms of which are worth summarizing here. First, Apple allegedly agreed to hand over control of e-book retail pricing to the publishers by allowing the publishers to appoint Apple as a mere agent; in return Apple would receive a 30 percent commission from the publishers for every e-book sold. Prior to this agency arrangement, publishers sold e-books through Amazon and others using a wholesale model that allowed retailers control of pricing, including discounts off the retail price.

Second, the Justice Department claims that the agreements effectively mandated that the publishers force Apple’s competitors – principally Amazon – to adopt the agency model, allowing the publishers to end price competition among all e-book retailers. Finally, the publishers apparently agreed to an unusual “most favored nation” clause in the agency agreements, under which the publishers guaranteed to Apple that they would lower the retail price of each e-book in Apple’s catalog to match the lowest price offered by any other retailer, even if the publisher did not actually control that retailer’s pricing.

According to the Justice Department complaint, the net effect of the agency agreements was that “Apple and Publisher defendants reached an agreement whereby retail price competition would cease (which all conspirators desired), retail e-book prices would increase significantly (which the Publisher Defendants desired), and Apple would be guaranteed a 30 percent ‘commission’ on each e-book it sold (which Apple desired).”

Facing these conspiracy allegations, it is perhaps unsurprising that three of the five publishers – Hachette, Harper Collins, and Simon & Schuster – have chosen to settle with the Department of Justice rather than to fight protracted antitrust litigation. The proposed settlements – which will need to be approved by a federal district court judge – require the publishers to terminate their agency agreement with Apple and to refrain from entering into similar agreements with any e-book retailer for two years.

So why have Apple and the remaining publishers – MacMillan and Penguin – elected to fight on? Both MacMillan and Penguin have responded quickly and publicly to the Justice complaint. In an open letter, the MacMillan CEO acknowledged that his company had “been in [settlement] discussions with the [Department of Justice] for months” but had chosen not to settle because “the terms the DOJ demanded were too onerous.” According to MacMillan, a settlement “could have allowed Amazon to recover the monopoly position it had been building before our switch to the agency model.”

Apple’s response to the Justice Department was more pointed still. According to its spokesperson Tom Neumayr “[t]he DOJ’s accusation of collusion against Apple is simply not true” and the “launch of the [Apple] iBookstore in 2010 fostered innovation and competition, breaking Amazon’s monopolistic grip on the publishing industry.” In other words, not only were Apple’s actions not anticompetitive they were, in fact, procompetitive.

Ultimately, the real reason that Apple, in particular, did not settle may well be antitrust law itself. To explain: while the Justice Department’s complaint may read like a Scott Turow novel, proving the allegations in it under existing antitrust laws could prove an uphill struggle for the government, particularly with respect to Apple. The contours of Apple’s likely defense are already discernible from its motion to dismiss the class action law complaints filed last year. In particular, Apple relies on two recent antitrust opinions handed down by the Roberts Court to make its argument. In 2007, the Supreme Court reversed longstanding antitrust law banning resale price maintenance, and held that manufacturers – in this case, the book publishers – could, in fact, mandate a minimum resale price to retailers.

Additionally, even if the e-book agency agreements suggest parallel conduct between Apple and the publishers, the company argues that recent antitrust law is still on its side. This is because in the other significant antitrust decision handed down by the Robert’s Court in 2007, the Court significantly increased the standard needed to plead a conspiracy beyond summary judgment. Under Twombly, in order to successfully plead a conspiracy, “allegations of parallel conduct” must “be placed in a context that raises a suggestion of a preceding agreement, not merely parallel conduct that could just as well be independent action.” According to Apple, the allegations against it “do not plausibly suggest Apple’s participation in a conspiracy” since it was not a horizontal competitor to the book publishers and had “no motive to protect” book publishing in general.

Consistent with its initial public reaction to the DOJ complaint, Apple also makes the argument in its motion to dismiss that its e-books launch should in fact be viewed as a procompetitive move. According to the company “[i]t would be a perverse use of antitrust law to condemn Apple for successfully entering a market with an innovative new product” that was expected to spur demand for e-books. Unfortunately for Apple, in so doing, e-book prices apparently increased overall. Such price changes will undoubtedly figure into the next chapter of the e-books saga, when the judge needs to reach a decision. You won’t want to put the book down.