PPR seminar focuses on the failure of private action to improve factory working conditions.

More than four hundred garment workers died last year when the Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, Bangladesh collapsed, despite recent efforts by multinational corporations to increase worker safety around the world.

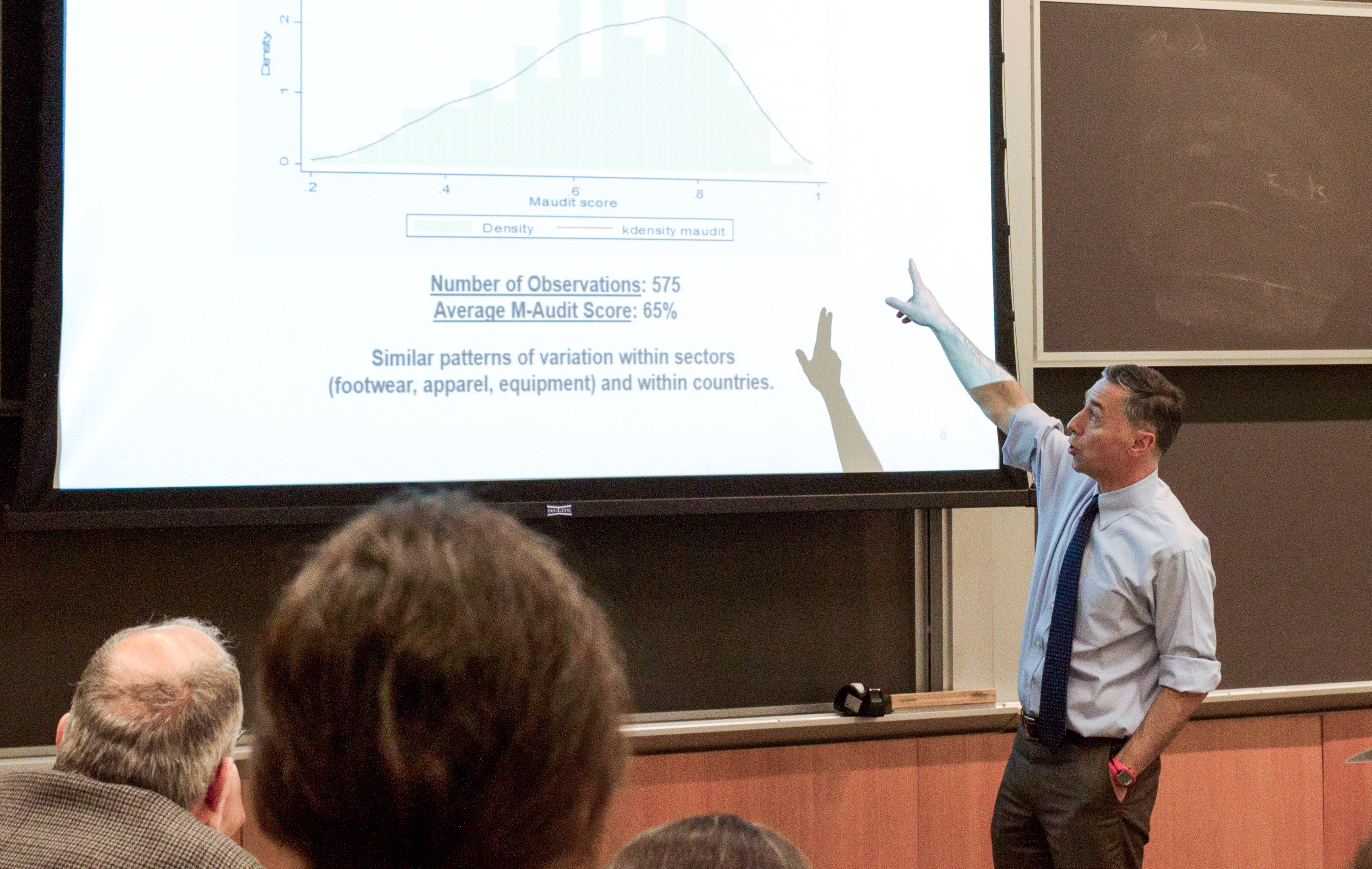

According to Richard M. Locke, a political science professor at Brown University, private regulation has not significantly improved workplace safety despite good faith efforts by corporations to enforce private labor standards on their suppliers. At a seminar sponsored by the Penn Program on Regulation, Locke described the results of an extensive, multi-year research project revealing that traditional corporate-sponsored audit programs have had a limited effect on worker conditions, but he also showed that there are new approaches to private regulation that are more promising.

Locke, the Howard R. Swearer Director of the Watson Institute for International Studies at Brown University, said the motivation for his research on worker safety issues stems not only from his interest in the effects of globalization on the market for retail goods, but from a genuine concern for the conditions under which people work. Child labor, excessive work hours, hazardous work conditions, and poor wages are rampant in factories in developing countries. Locke’s ultimate hope is that corporations who source their goods and materials from these factories can find more effective ways to reduce or eliminate harsh conditions for workers who create their products.

Locke began his research by studying the suppliers for Nike. His research methodology involved reviewing thousands of audit reports, visiting one hundred and twenty factories in fourteen different countries, and conducting more than seven hundred interviews with company managers, factory directors, NGO representatives, and government labor inspectors. He later expanded his research to review the audit practices of Hewlett-Packard, Apple, and a large clothing retailer.

The traditional method of private regulation of factory conditions consists of requiring suppliers to sign onto buyer-created codes of conduct and then conducting audits and inspections of factories to assess compliance with these codes. When suppliers are found to be out of compliance, the buyer may reduce its orders or even end its relationship with a supplier altogether, depending on the severity of the failure.

Most of the buyer audits Locke reviewed revealed the need for some improvements in factories, but none of the violations were so extreme that the buyers penalized the non-complying suppliers in a manner that would lead to long-lasting changes. Locke’s research showed that over time and across several audits, this traditional method did almost nothing to improve overall factory conditions.

Locke observed that the discrepancy behind the corporate rhetoric that touts dedication to worker safety, and the reality of the actual conditions, results not from a lack of will, moral fiber, interest or dedication of resources. In fact, he said, corporations spend millions of dollars on private regulation with hopes to see changes.

“I thought I would find [a company] who does it right, but I didn’t,” Locke said. He went on to say that he believes the reason is that flaws are within the traditional compliance model itself, and have little to do with efforts and intentions of companies.

Locke believes the traditional compliance model fails to work well due to complicated power dynamics between the buyers and suppliers as well as the inability to generate accurate information about the actual conditions of a factory. Often suppliers know when an audit will occur, so they prepare the factory for the audit and then let conditions deteriorate until the next audit. Furthermore, some of these factories are supplying huge percentages of products for many different global brands, and corporations are not willing to reduce inventory and profits in a given year or season just because of a bad audit report.

According to Locke, a better approach to improving working conditions seems to be for buyers to engage in “capability building.” This approach is based in “root cause analysis” of problems where buyers observe an issue in a particular factory and provide the factory managers with organizational skills and technical assistance so they can fix the problems. By providing suppliers with know-how to run their businesses in a more effective manner, they are able to invest in higher wages and better working conditions.

However, capability building has also had mixed results, which Locke perceives to be correlated with the amount of interaction between the buyer and supplier. The buyers who were committed to long-term relationships with suppliers showed better results than those who interacted with suppliers in a limited manner.

New trends in consumption are also to blame for poor worker conditions, Locke said. His prime example was in the consumer electronics industry, where the life cycle of many products is less than a year. With shorter life cycles, buyers are asking suppliers to create smaller shipments of more customized products so retailers do not have to hold large, out-of-date inventories. Such practices put strains on suppliers, as their customers pressure them to work harder and longer to meet such demands.

In the end, Locke does not reject the role for private regulation of labor conditions, but he argued at the talk that private efforts need to be used to complement or enhance government enforcement of labor laws. He also said that in order for private regulation to be successful, there must be “collaboration among key actors within and across firms, … built through repeated interactions and mutual understanding that all parties must share the benefits and costs.”

Locke’s talk, held at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania as a part of the risk regulation seminar series jointly organized by the Penn Program on Regulation and the Wharton Risk Center, drew on his new book, The Promise & Limits of Private Power: Promoting Labor Standards in a Global Economy, recently published by Cambridge University Press.