It remains to be seen whether industry efforts to fight hydraulic fracturing regulation will succeed.

Hydraulic fracturing, more commonly known as fracking, has generated significant controversy and elicited starkly contrasting political responses. Some state and local governments actively encourage fracking, citing economic benefits of the domestic natural gas boom. Others have limited or even banned its practice due to environmental concerns.

The fracking industry has responded to state and local regulations and prohibitions with two primary types of lawsuits: preemption challenges, which argue that federal law prevents state governments from passing fracking restrictions (and that state law prevents local governments from doing the same); and Takings Clause challenges, which argue that the federal constitution entitles a company to compensation when a fracking ban or limitation renders that company’s land useless.

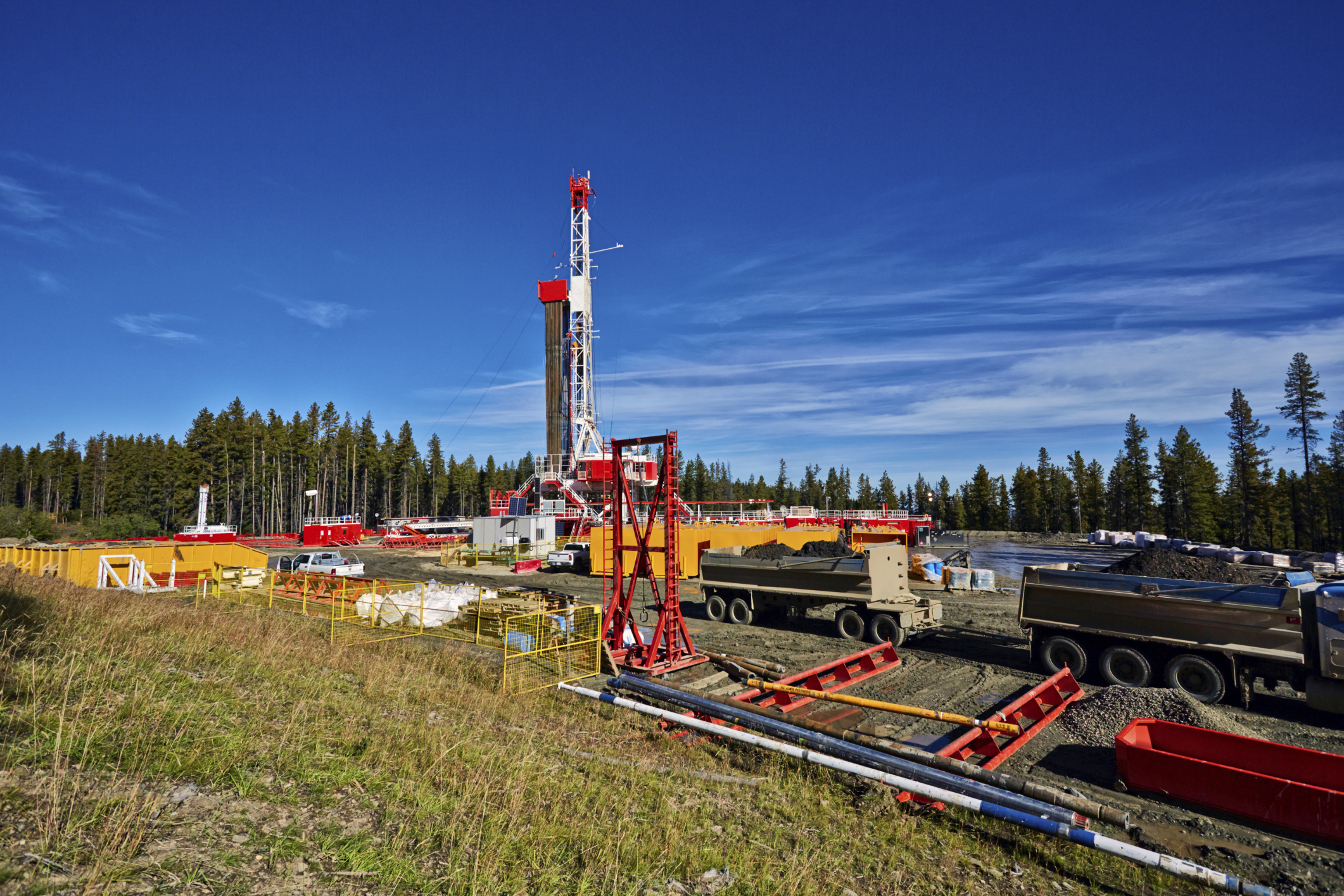

Fracking is an advanced drilling process where water, sand, and chemicals are pumped, under pressure, into a well bore to release previously inaccessible oil and gas from an underground rock formation. Industry officials point to lower consumer gas bills, job growth, and energy independence as major benefits of fracking. But environmentalists express concerns. Fracking wastewater may induce earthquakes, contaminate groundwater and surface water, and create health risks. The noisy operations often irritate neighbors and reduce property values.

These risks have persuaded a handful of state governments to regulate site location, design, and chemical use. In June, after a four-year temporary fracking ban, New York finalized its prohibition, becoming the only state with significant gas resources to forbid fracking entirely. Maryland recently banned fracking for two and a half years. Several municipalities have also regulated fracking through strict zoning regulations or outright bans.

Given the significant investment needed to acquire property rights and start a fracking operation, industry groups and energy companies have not been reluctant to take forceful legal action, filing claims which seek to force municipalities adopting restrictions to pay millions of dollars in compensation. Industry officials state that such lawsuits are necessary to prevent loss, but communities characterize them as little more than a “scare tactic.”

What kinds of claims exactly do these lawsuits raise? One approach a fracking company might take is to file a preemption challenge. When a state law and local law explicitly or implicitly conflict, the more localized law is said to be “preempted” and is thrown out.

Preemption lawsuits challenging local fracking bans have produced mixed results. The Pennsylvania Supreme court upheld a local fracking ban in 2013, and a New York court did the same in 2014, each finding that state law did not override municipal power. And yet in 2014, a Colorado trial court judge disposed of a local ban because it conflicted with the state’s fracking regulations and the state’s overall interest in efficient oil and gas development.

Similarly, a company might argue that a federal law preempts a state or local fracking ban. Although no such lawsuit has yet been heard involving a statewide ban, a New Mexico court recently found that federal law preempts a local ban.

When a company cannot prevail in a preemption lawsuit, it might next file suit under the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. In such a case, the company would demand “just compensation” by asserting that the state or local fracking ban makes its property less useful.

The outcome of a takings lawsuit is not readily predictable: given that fracking bans have only recently taken effect, no relevant takings challenge has been fully litigated. Furthermore, takings cases are notoriously complex and inconsistent. No court has ruled on the issue, but takings suits have been filed in state courts and are likely to be filed to challenge the New York ban.

To win a takings case, a company would first attempt to prove a “total taking,” arguing that the fracking ban leaves its property with no value. If the company successfully proves a total taking, then the government would be more limited in the evidence it could introduce to defend the ban.

The University of Denver’s Kevin Lynch, who has defended fracking bans in Colorado, contends that industry groups and energy companies will be unable to prove a total taking. He points to the so-called denominator problem as their primary obstacle: a fracking company will have a difficult time defining the scope of its property so narrowly that a ban renders the property valueless. Even if state law allows the mineral estate to be considered separately from the surface property, Lynch argues, a total takings claim cannot proceed if the mineral estate in question has any remaining value or might one day produce oil and gas without fracking.

Industry leaders disagree. Attorneys at the firm of Sidley Austin, which represents natural gas companies, argue that a company leasing mineral rights has a particularly strong basis for a takings claim, as a fracking ban is likely to deplete a given mineral estate of all of its economically beneficial use. Whether this argument will succeed, they concede, depends on the mineral composition of the given property and the broadness of the particular ban.

Even if a total taking has not occurred, though, a company might allege a “partial taking.” Faced with such a claim, a court is supposed to make an “ad hoc, factual inquiry,” taking into account the government’s purpose in enacting the fracking ban, whether a fracking profit was probable given industry and regulatory conditions, and the economic impact on the company.

Given that the government can introduce public health and safety evidence when defending partial takings claims, Lynch argues that partial takings claims, too, are unlikely to succeed.

Nonetheless, industry leaders and attorneys remain optimistic that they can demonstrate partial takings. For example, Sidley Austin attorneys note that during partial takings cases, judges may consider significant economic difficulties created by fracking bans as well as the adequacy of the government’s scientific basis for implementing the ban.

In addition to preemption and takings claims, yet another, albeit untested, type of legal challenge recently emerged when a New York landowner filed suit, claiming that no scientific research exists to back up New York’s fracking ban.

As natural-gas trade groups weigh whether to file suit as well, the industry also considers alternatives to litigation. In early July, for example, an energy company applied to drill a natural-gas well using a waterless method that would purportedly circumvent New York’s fracking ban.

Only with the passage of more time will we know how well fracking regulations will fare in court.