Peter Schuck’s book illustrates how the law is an important, though imperfect, tool in preserving natural phenomenon.

Peter Schuck’s magisterial reflection on Why Government Fails So Often is worthy of the attention it is receiving. In chapter nine of his book, Schuck notes that “law’s strengths are formidable and essential,” but he also draws attention to how “its inherent limits…seriously diminish law’s performance and reputation.” He thoughtfully examines seven of these limits: law’s ubiquity; the simplicity-complexity trade-off; ambiguity; discretion; procedural apparatus; inertia; and the effects of crowding-out on spontaneous, low-cost cooperation.

In a book filled with so many examples and powerful arguments, I find myself drawn to one reference – made in passing – to the Grand Canyon. “The law designating parts of the Grand Canyon as a national park,” Schuck writes, “transformed it from an awesome natural panorama into an object of administration.”

Two aspects of that statement intrigue me. The first is that it skips a step. Actually, the law transformed the Grand Canyon “from an awesome natural panorama” into private property to be exploited for private gain, and then “into an object of administration.”

The Grand Canyon did not become a national park until 1919, nearly fifty years after Yellowstone. It was in fact the eleventh national park, established after less memorable places such as Wind Cave in South Dakota and Lassen Volcanic in northern California.

The Grand Canyon area was functionally lawless until the late nineteenth century. That began to change when explorers encountered the Grand Canyon and began to extol its scenic virtues. Indiana Senator Benjamin Harrison introduced the first bill to establish the Grand Canyon as a national park in 1882, but when that failed, he unilaterally transformed the area into a forest reserve in his last days in office as a lame-duck president in 1893. Teddy Roosevelt took up the cause as well – but he, too, failed to turn the Grand Canyon into a national park during his presidency.

The delay in establishing the Grand Canyon as a national park resulted from the determined use and abuse of the law by one man: Ralph Cameron, who moved to Arizona in 1882 and soon began charging tourists for the use of an old Havasupai trail that led down into the Grand Canyon. Cameron staked a mining claim to the area based on the Mining Law of 1872 – then only 11 years old, but still in nearly total effect today – and asserted that his claim entitled him to charge visitors for entrance and egress across public land. He held onto that Mining Law claim until the Supreme Court invalidated it in 1920, one year after Congress established the Grand Canyon National Park. In the end, Cameron was able to exploit a wrongful use of the Mining Act for 38 years – long after the law suggested otherwise – to serve his private benefit.

The saga of the Grand Canyon, in short, offers a much richer story of law than the seemingly simple transformation from scenic splendor to object of administration than Schuck’s statement suggests.

The second intriguing aspect of Professor Schuck’s casual reference to the story of the Grand Canyon involves what it means to be “an object of administration.” Law is indeed ubiquitous in that process, as Professor Schuck observes. The operative provision of the Organic Act, which has governed the National Park Service (NPS) for 98 years, simply states that national parks are to be managed “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” That’s it. The Organic Act is decidedly on the simplicity side of “the simplicity-complexity trade-off” that Professor Schuck describes, especially compared to modern environmental laws like the Clean Air Act.

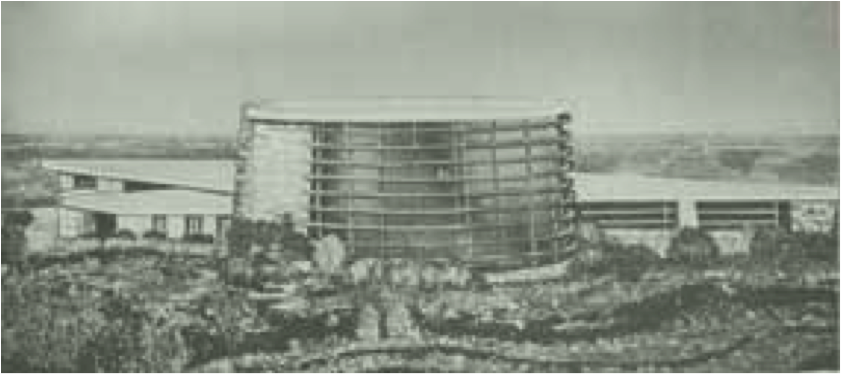

It is surprising how little law actually guides NPS management decisions, especially given the deference that the courts afford to NPS applications of the Organic Act. For example, the “Shrine of the Ages,” proposed during the 1950s as a place for worship services near the rim of the Grand Canyon, was never built, in part because people could not tell whether it looked like a native American kiva (as was intended) or a spaceship. You can decide for yourself:

Consider another example: the NPS recently prepared a Bison Management Plan for Grand Canyon National Park as a result of the failed efforts of an early twentieth century entrepreneur who brought bison to northern Arizona and bred them with cattle in an attempt to create a superior, more robust breed of livestock, the “cattalo.” The descendants of the bison migrated into the national park less than twenty years ago, threatening other park resources such as soils, vegetation, archeological sites, and water resources.

More recently, elk harassment of people was the unintended consequence of the NPS pursuing environmental sustainability goals by eliminating sale of bottled water in the national park. The NPS installed water fountains for thirsty tourists, but the elk quickly learned how to turn on the spigots and then asserted a proprietary claim to their new source of desert water.

The NPS makes management decisions like these with only a modest amount of law to guide it. Of course, Congress may intervene if those decisions are unpopular. That is what has happened with motorized rafting within the Canyon and scenic flights over the Canyon, which are both regulated by additional laws. Even so, disputes over those activities persist, just as Schuck would have predicted.

The Grand Canyon is a powerful illustration of the limits of the law that Schuck describes in his book. It is an object of administration, to be sure, but the Grand Canyon also remains an awesome natural panorama. The law, as usual, is a valuable but imperfect tool for pursuing society’s vision of both public administration and the preservation of the nation’s natural wonders.

This essay is part of The Regulatory Review’s seven-part series, Is Government Prone to Fail?

The above conception picture of the Shrine of Ages is provided courtesy of the National Park Service.