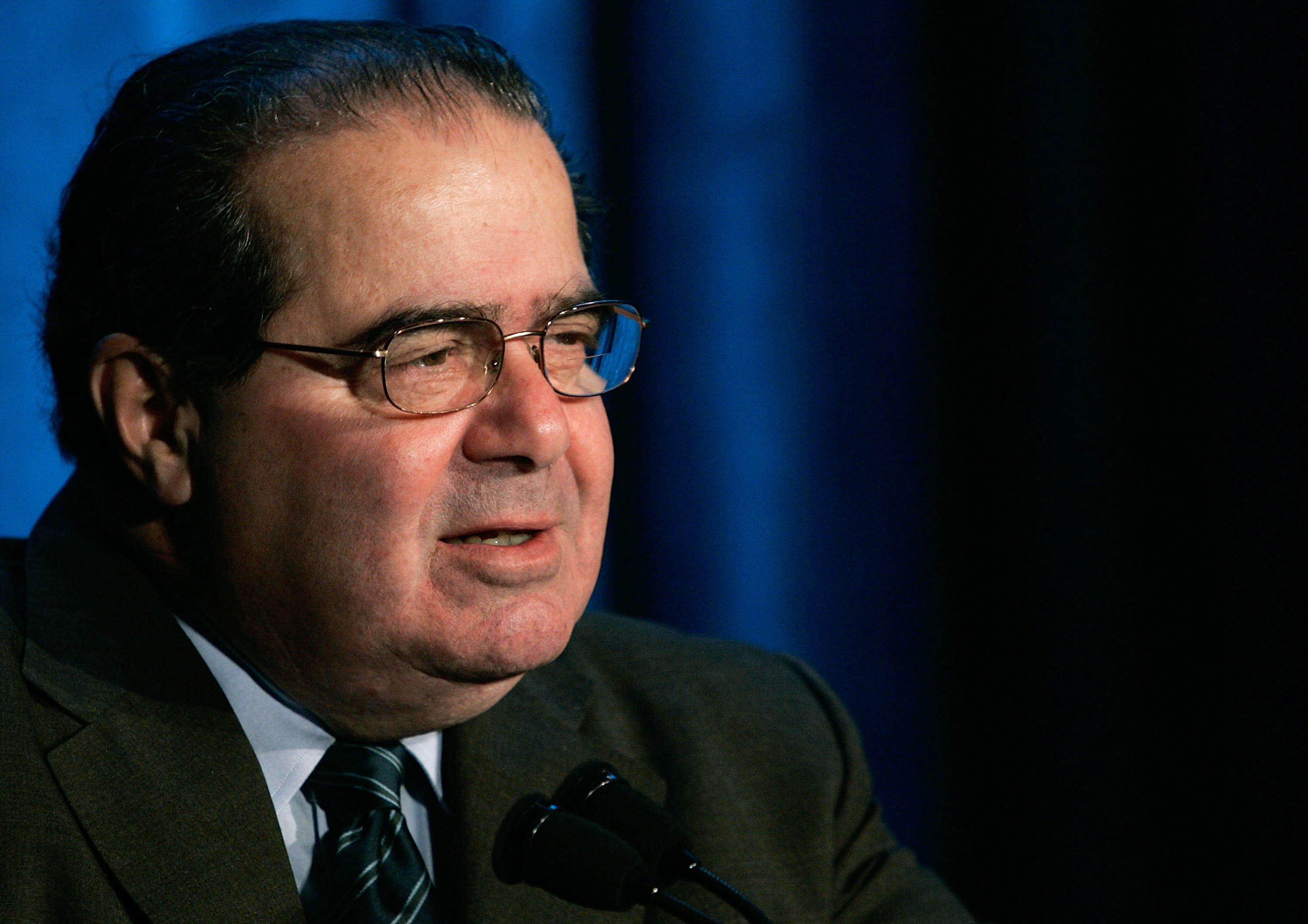

The Regulatory Review reflects on the late Justice Scalia’s most consequential—and colorful—opinions in administrative law.

In the days following Justice Scalia’s sudden passing, he has been celebrated for the intellectual rigor that he brought to the Supreme Court, for his unwavering commitment to originalism and textualism, and for the witty, colorful, and at times blistering language of his judicial opinions. All of these qualities infused the many opinions that he authored concerning executive discretion, regulatory procedures, and other foundational administrative law matters. In commemoration of Justice Scalia’s distinguished, thirty-year career on the United States’ highest court, The Regulatory Review presents excerpts from some of his most prominent administrative law opinions.

That is what this suit is about. Power. The allocation of power among Congress, the President, and the courts in such fashion as to preserve the equilibrium the Constitution sought to establish—so that “a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department,” can effectively be resisted. Frequently an issue of this sort will come before the Court clad, so to speak, in sheep’s clothing: the potential of the asserted principle to effect important change in the equilibrium of power is not immediately evident, and must be discerned by a careful and perceptive analysis. But this wolf comes as a wolf.

– Dissenting in Morrison v. Olson (1988)

The question presented here is whether the public interest in proper administration of the laws (specifically, in agencies’ observance of a particular, statutorily prescribed procedure) can be converted into an individual right by a statute that denominates it as such, and that permits all citizens (or, for that matter, a subclass of citizens who suffer no distinctive concrete harm) to sue. If the concrete injury requirement has the separation-of-powers significance we have always said, the answer must be obvious: To permit Congress to convert the undifferentiated public interest in executive officers’ compliance with the law into an “individual right” vindicable in the courts is to permit Congress to transfer from the President to the courts the Chief Executive’s most important constitutional duty, to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

– Writing for the Court in Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife (1992)

In support of their position, petitioners cite dictionary definitions contained in, or derived from, a single source, Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, which includes among the meanings of “modify,” “to make a basic or important change in” . . . . If that is what the peculiar Webster’s Third definition means to suggest has happened—and what petitioners suggest by appealing to Webster’s Third—we simply disagree. “Modify,” in our view, connotes moderate change. It might be good English to say that the French Revolution “modified” the status of the French nobility—but only because there is a figure of speech called understatement and a literary device known as sarcasm. And it might be unsurprising to discover a 1972 White House press release saying that “the Administration is modifying its position with regard to prosecution of the war in Vietnam”—but only because press agents tend to impart what is nowadays called “spin.” Such intentional distortions, or simply careless or ignorant misuse, must have formed the basis for the usage that Webster’s Third, and Webster’s Third alone, reported.

– Writing for the Court in MCI Telecommunications Corp. v. American Telephone & Telegraph Co. (1994)

Generally speaking, the term “inferior officer” connotes a relationship with some higher ranking officer or officers below the President: Whether one is an “inferior” officer depends on whether he has a superior. It is not enough that other officers may be identified who formally maintain a higher rank, or possess responsibilities of a greater magnitude. If that were the intention, the Constitution might have used the phrase “lesser officer.” Rather, in the context of a Clause designed to preserve political accountability relative to important Government assignments, we think it evident that “inferior officers” are officers whose work is directed and supervised at some level by others who were appointed by Presidential nomination with the advice and consent of the Senate.

– Writing for a unanimous Court in Edmond v. United States (1997)

Justice Stevens thinks it is enough that respondent will be gratified by seeing petitioner punished for its infractions and that the punishment will deter the risk of future harm. . . . Obviously, such a principle would make the redressability requirement vanish. By the mere bringing of his suit, every plaintiff demonstrates his belief that a favorable judgment will make him happier. But although a suitor may derive great comfort and joy from the fact that the United States Treasury is not cheated, that a wrongdoer gets his just deserts, or that the Nation’s laws are faithfully enforced, that psychic satisfaction is not an acceptable Article III remedy because it does not redress a cognizable Article III injury. Relief that does not remedy the injury suffered cannot bootstrap a plaintiff into federal court; that is the very essence of the redressability requirement.

– Writing for a unanimous Court in Steel Co. v. Citizens for a Better Environment (1998)

Congress, we have held, does not alter the fundamental details of a regulatory scheme in vague terms or ancillary provisions—it does not, one might say, hide elephants in mouseholes. Respondents’ textual arguments ultimately founder upon this principle.

– Writing for a unanimous Court in Whitman v. American Trucking Associations (2001)

[I]t might be more accurate to say the Commission has attempted to establish a whole new regime of non-regulation, which will make for more or less free-market competition, depending upon whose experts are believed. The important fact, however, is that the Commission has chosen to achieve this through an implausible reading of the statute, and has thus exceeded the authority given it by Congress.

– Dissenting in National Cable & Telecommunications Association v. Brand X Internet Services (2005)

In setting the Phase II national performance standards and providing for site-specific cost-benefit variances, the EPA relied on its view that § 1326(b)’s “best technology available” standard permits consideration of the technology’s costs, and of the relationship between those costs and the environmental benefits produced. That view governs if it is a reasonable interpretation of the statute—not necessarily the only possible interpretation, nor even the interpretation deemed most reasonable by the courts.

– Writing for the Court in Entergy Corp. v. Riverkeeper, Inc. (2009)

[T]he requirement that an agency provide reasoned explanation for its action would ordinarily demand that it display awareness that it is changing position. An agency may not, for example, depart from a prior policy sub silentio or simply disregard rules that are still on the books. And of course the agency must show that there are good reasons for the new policy. But it need not demonstrate to a court’s satisfaction that the reasons for the new policy are better than the reasons for the old one; it suffices that the new policy is permissible under the statute, that there are good reasons for it, and that the agency believes it to be better, which the conscious change of course adequately indicates. This means that the agency need not always provide a more detailed justification than what would suffice for a new policy created on a blank slate.

– Writing for the Court in FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc. (2009)

The question here is whether a court must defer under Chevron to an agency’s interpretation of a statutory ambiguity that concerns the scope of the agency’s statutory authority (that is, its jurisdiction). The argument against deference rests on the premise that there exist two distinct classes of agency interpretations: Some interpretations—the big, important ones, presumably—define the agency’s “jurisdiction.” Others—humdrum, run-of-the-mill stuff—are simply applications of jurisdiction the agency plainly has. That premise is false, because the distinction between “jurisdictional” and “nonjurisdictional” interpretations is a mirage. No matter how it is framed, the question a court faces when confronted with an agency’s interpretation of a statute it administers is always, simply, whether the agency has stayed within the bounds of its statutory authority.

– Writing for the Court in City of Arlington v. FCC (2013)

The Court’s decision transforms the recess-appointment power from a tool carefully designed to fill a narrow and specific need into a weapon to be wielded by future Presidents against future Senates. To reach that result, the majority casts aside the plain, original meaning of the constitutional text in deference to late-arising historical practices that are ambiguous at best. The majority’s insistence on deferring to the Executive’s untenably broad interpretation of the power is in clear conflict with our precedent and forebodes a diminution of this Court’s role in controversies involving the separation of powers and the structure of government. I concur in the judgment only.

– Concurring in the Court’s judgment in NLRB v. Noel Canning (2014)