FDA issues new guidelines to medical device manufacturers to mitigate cybersecurity concerns.

Consider a typical scenario in which a hospital patient receives regular doses of intravenous medication through an infusion pump. Today, that infusion pump is also connected to the hospital’s Internet network. Now, consider what would happen if an outsider hacked into both the patient’s device and the network on which it operates, accessing private medical records while posing a direct threat to the patient.

This scenario is all too plausible, according an article written about “white hat hacker” Billy Rios. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has taken note, recently acknowledging that existing security evaluations and controls of medical devices cannot sufficiently protect against hacks.

The FDA recently released a set of draft guidelines urging medical device manufacturers to strengthen cybersecurity protections. This guidance responds to security concerns voiced through Executive Order 13636 and Presidential Policy Directive 21, as well as warnings from security professionals.

The guidelines apply to medical devices that contain software or software used as a medical device. The agency’s draft outlines six points for post-market assessment and remediation of cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Specifically, the FDA recommends that device manufacturers define and document mitigation processes around both the exploitability of the cybersecurity risk, and the severity of the health impact to patients if the vulnerability in a device is exploited.

The FDA’s interest in medical device security is not completely new. In 2013, the agency released a guidance on manufacturers’ management of pre-market cybersecurity issues in medical devices. In 2015, it alerted the public about apparent vulnerabilities in a Hospira infusion device along the lines of what white-hat hacker Rios described in the article about him. Yet, according to one agency representative, the Hospira alert was the first time a product was called out for cybersecurity issues.

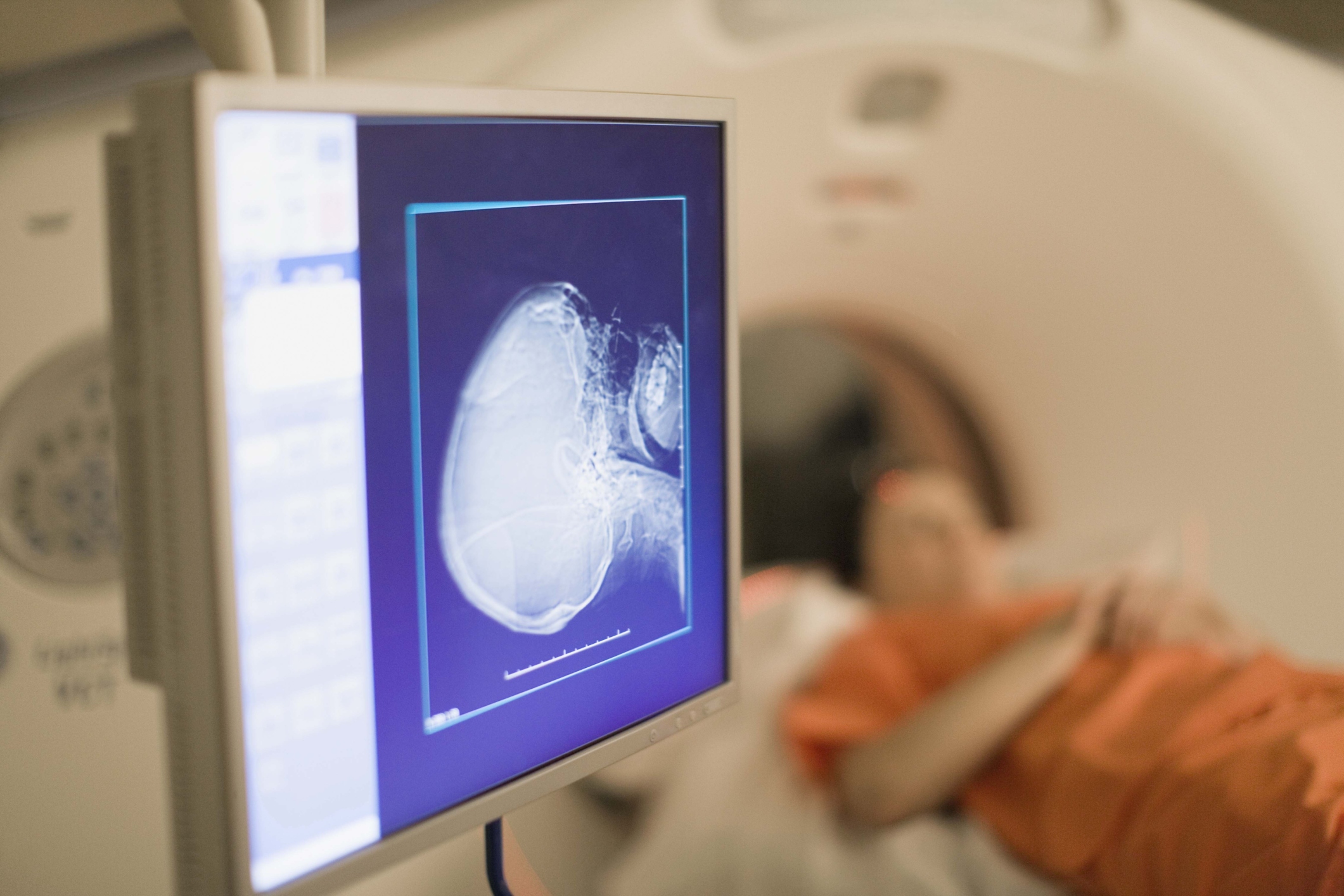

But other devices have vulnerabilities too. Researchers describe security flaws of medical devices such as MRI scanners and x-ray machines, in addition to infusion pumps. At last year’s DerbyCon, a conference for security professionals, experts Scott Erven and Mark Collao explained that vulnerabilities in medical devices allow for any willing hacker to intrude. Such flawed security does not align with patient safety needs.

Consumers knowledgeable about patient health record security might question why the FDA’s current guidance has significance, given preexisting data security and privacy laws such as HIPAA and the HITECH Act. However, these laws govern and limit the transfer of patient information between health care providers. They do not instruct manufacturers to create safeguards for devices that collect such patient data.

In spite of security warnings, some legal professionals claim that the harm caused by medical device hacking remains speculative. Government responses to device vulnerabilities may lead manufacturers to overreact and install security solutions that impede useful functions of devices.

However, according to security experts, the threat of medical device breaches has not waned. Rather, proliferation of networked medical devices has increased the potential scope of this security issue, and has amplified the concerns signaled by privacy experts.

Nevertheless, Steven Bornian, partner at Reed Smith, argues that despite limitations to any potential threat, the FDA cannot take any other approach than what it is currently taking. For Bornian, risks associated with medical devices can never be extinguished completely.

For now, the FDA’s current risk-based approach recommends that device manufacturers provide users with work-arounds and temporary fixes in the event of a data breach. The FDA’s approach evaluates threats on a spectrum of risk defined by two poles: controlled risk and uncontrolled risk. The level of risk identified on this spectrum depends on how a cyberthreat might affect the essential clinical performance of a device.

With this open strategy, the FDA intends to collect comments and make future modifications, given the constantly evolving nature of cybersecurity risks.