According to experts on a recent panel, identifying, measuring, and tackling capture should be a top priority for government.

Regulations are supposed to ensure that our drinking water is potable, our workplaces are safe, and our financial transactions are secure. In short, regulations are meant to protect us. But what happens when regulated industries exert so much influence on regulators that the regulations skew toward protecting industries’ interests rather than the public’s? That scenario is called regulatory capture, and it appears to occur more often than we might like, according to a dialogue held earlier this spring at the Administrative Conference of the United States (ACUS), an independent agency that acts as a good-government think-tank.

Regulatory capture is a particularly vexing problem in the rulemaking context, where regulations may be created that are out of sync with the public interest. This is not a new concern, but because it occurs in the shadows, hidden from public scrutiny, it is a difficult problem to tackle. So how can we identify and measure, let alone cure, the problem of regulatory capture in the rulemaking process?

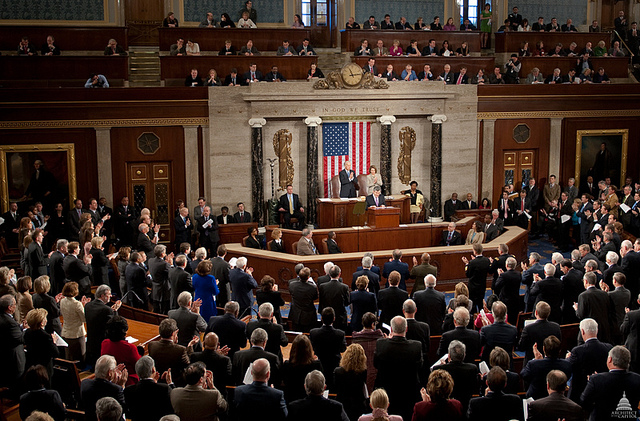

To explore these questions, this spring, the ACUS convened a panel discussion of leading scholars who study regulatory capture.

Steve Croley, the ACUS vice-chair and the U.S. Department of Energy’s General Counsel, moderated the panel’s discussion. Croley honed in on four key issues for the panelists to consider: defining capture, describing an “uncaptured” regime, assessing the costs and benefits of various solutions, and determining whether the solution should be preventative or an after-the-fact remedy.

The discussion of defining capture—and, in particular, how to distinguish it from mere influence—began with panelist Dan Carpenter, a Harvard University professor. He referenced the definition from his recent book, co-edited with David Moss of the Harvard Business School, Preventing Regulatory Capture. Carpenter and Moss define capture as a state in which regulation “is consistently or repeatedly directed away from the public interest and toward the interests of the regulated industry, by the intent and action of the industry itself.”

Another panel member, Sidney Shapiro, a professor at Wake Forest University School of Law, argued that when agencies frequently adopt regulations favoring the regulated entities, it “raises at least an inference of capture.”

Capture, though, is “not a binary situation,” Carpenter argued. It “can be weak or strong.”

Another panelist, Mark Calabria of the Cato Institute, alluded to a similar spectrum of capture. In the “easy” cases, capture is obvious, he claimed, and the answer is simple—“just don’t do it.” He gave as an example licensing requirements for hairdressers, where he claims little to no public benefits result from them, but which tend to raise restrict consumer prices. He claims these regulatory schemes are “pure rent seeking capture.”

In the harder cases, Calabria noted, regulatory schemes will offer clearer public benefits, but will also provide opportunities for private gains too.

So what would an “uncaptured” regime look like? Carpenter argued that one good marker would be the absence of industry advantages in the notice and comment rulemaking process.

Panelist Neomi Rao, a professor at George Mason University’s recently renamed Antonin Scalia Law School, asserted though, that it is difficult to envision an uncaptured regulatory regime because the public interest is hard to pinpoint. Because of this, she emphasized the importance of a fair lawmaking process.

Rao drew attention to the frequency of Congress’ delegations of authority to agencies, often made in the interest of accomplishing policy ends in a gridlocked legislature. But when these delegations occur, she argued, the constitutional processes meant to safeguard the public interest are subverted. Instead, Rao noted that it may create another type of regulatory capture—this time by the legislators who can often get more done by working with the agencies than through legislation.

Calabria reasoned that much of the problem boiled down to simplicity. “Complexity,” he argued, “is the friend of industry.” According to Calabria, the more complex regulation is, the easier it is for industry to influence the policy outcome and the harder it is for the public to monitor in a meaningful way. Additionally, he noted that for agencies that regulate a small number of entities, and sometimes even depend on those same entities for funding, the susceptibility for capture is high.

Calabria also pointed to outsized reliance on lawyers in the rulemaking process as a problem, because lawyers tend not to understand the economics well. Instead, Calabria – himself an economist – called for a multidisciplinary approach that would give various professions a seat at the table in the rulemaking process.

Possible remedies for addressing capture also have costs and benefits. One example Carpenter discussed was agency reliance on universities for research and expertise. Universities are often seen as preferable source of expertise compared with industry, but they are not above the fray of regulatory capture. Given the many corporate partnerships involved in university research, Carpenter contended, universities are “sometimes as much the problem as the solution.”

In closing, the panelists probed Croley’s question of whether the cure for regulatory capture should focus more on “prophylactic” or “ex post” solutions, each positing potential steps to help check regulatory capture. Carpenter suggested that dispatching inspectors general, dedicated to the task of rooting out capture would be a good start.

Shapiro, on the other hand, advocated for thorough study of the effects of decreased agency funding as well as for consideration of ways to improve the transparency of meetings within the agencies and for the creation of useful metrics to assess regulatory progress.

Meanwhile, some appeared to agree that Rao’s suggestion hit perhaps closest to the source of capture, admonishing Congress to stop delegating so much of its authority to agencies in the first place.

The panel obviously did not solve the problem of regulatory capture in the course of the morning’s discussion, but the panel members’ conversation elucidated key areas where ACUS, other agencies, and Congress can focus their energies on remedying defects in the regulatory process.

This essay is part of The Regulatory Review’s sixteen-part series, Rooting Out Regulatory Capture.