The President’s one-in, two-out executive order may be difficult to implement, but it is not unconstitutional.

In their recent essay appearing in The Regulatory Review, Scott Slesinger and Robert Weissman declared that Executive Order 13,771, which directs agencies to repeal two existing regulations for every new regulation they seek to promulgate, is unconstitutional. The constitutionality of regulatory reform appears to be an emerging theme in 2017, as at least one other group has argued separately that another tool for regulatory reform—the Congressional Review Act, passed by both houses of Congress and signed by President Bill Clinton in 1996—is also unconstitutional. Although Slesinger and Weissman might have legitimate policy objections to Executive Order 13,771 and its application of regulatory budgeting, claims of that order’s unconstitutionality are premature.

Can anyone point to one instance when the Trump Administration rescinded a regulatory standard to satisfy the one-in, two-out order? According to the American Action Forum (AAF), the Administration has not finalized a single major regulatory action that would trigger the need for two or more deregulatory actions under the executive order. It is hard to see how anyone can have standing in court to challenge an executive order that has yet to lead to any changes in regulations.

Slesinger and Weissman’s argument explaining the lawsuit filed by their organizations—the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Public Citizen, respectively—is filled with speculative language that shows that any constitutional suit against the executive order is far from ripe for judicial review. Words and phrases such as “potentially,” “will make,” “would inflict,” and “will have,” can be found throughout their essay. Are not courts more interested in actual harms that result in victims from agency action? What harm can Public Citizen or the NRDC claim from the executive order, which has yet to lead to a repeal of a regulation about which they are concerned?

Furthermore, Slesinger and Weissman, along with other critics of regulatory budgeting, seem to forget crucial language contained in EO 13,771: “unless prohibited by law,” a phrase that appears four times in the executive order. In rhetoric, strawmen are erected and burned that seem to depict an alternate reality where the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) must choose between clean air and clean water. Because there are statutes directing EPA to preserve both, the Agency will not have to abandon particulate matter standards if it seeks to implement a clean water rule. If it did, the Agency would surely lose in court.

The dictates of existing statutory law still remain; Executive Order 13,771 does not change the law, just the priorities. This executive order, as countless previous executive orders have done, merely moves the margins of regulation. There were no cries of unconstitutionality when President Barack Obama issued Executive Order 13,563 directing agencies to conduct retrospective review to see if they should “modify, streamline, expand, or repeal” existing regulations. Although progressives had policy objections when President Obama repealed or significantly modified rules, there were no constitutional lawsuits racing toward the courts. Indeed, President Obama cut costs from final rules more than 100 times during his Administration. Would President Trump be prohibited from replicating and building on those successes?

Marcus Peacock, who led the “landing team” at the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs during the first few months of 2017, offered some hints about how the one-in, two-out budget might work at a recent Resources for the Future event. He cited both Canada and the United Kingdom, which have operated regulatory budgets without abandoning clean air or water standards. In those countries, reducing paperwork—through recordkeeping and reporting requirements—dominates the deregulatory actions. Peacock predicted similar actions for the United States. He stated, “I’m guessing we’re going to find something similar. And a lot of the deregulatory actions that people will focus on first are those that simply make it easier for people to fill out paperwork or just fill out less paperwork, probably.” From that remark, it is hard to spot the fundamental constitutional conflict between Executive Order 13,771 and existing law.

Indeed, with every administration, regulators trim paperwork and reduce regulatory costs without flouting the intent of Congress or their statutory directives. For example, during the Obama Administration, the U.S. Department of Transportation revised its rule on driver vehicle inspection reports. This rulemaking relieved truck drivers from having to file “no defect” reports. Essentially, they no longer had to report that their trips from one city to another occurred without incident. According to the Obama Administration, this saved $1.7 billion annually by cutting 46.6 million paperwork burden hours.

This is not to say that implementation of the executive order will be a walk in the park. On the contrary, it will be difficult. Fulfilling the executive order’s requirements will demand a robust retrospective review and program evaluation initiative from agencies. Perhaps this effort might give rise to new agencies that will aid in the effort.

Following Executive Order 13,771 might prove difficult for some agencies, but the action itself is hardly unconstitutional. If the Administration starts uprooting particulate matter and carbon monoxide standards as a prerequisite for issuing new major rules, perhaps there will be a case. If instead, the margins of existing regulations are reworked to decrease costs—which, in some cases, is no easy task—then the executive order will remain in place for the foreseeable future.

This essay is part of a four-part series, entitled A Debate Over President Trump’s “One-In-Two-Out” Executive Order.

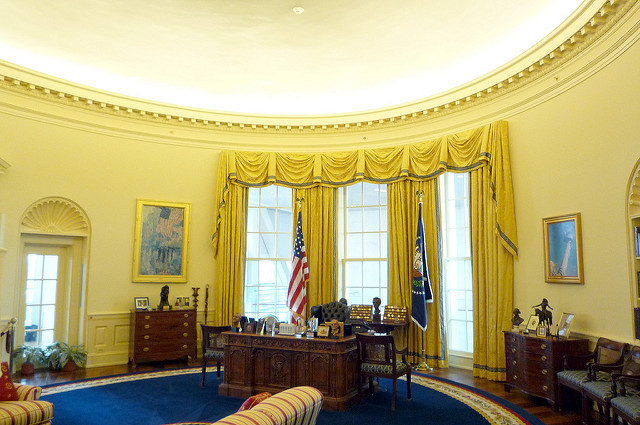

The image of the White House’s Oval Office is used unaltered under a Creative Commons license.