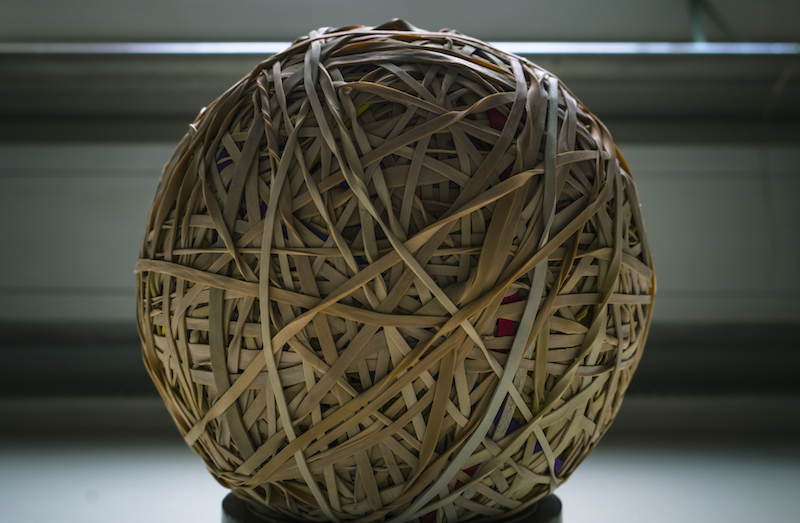

Net neutrality has “bounced” from regulation to repeal under an often-used administrative law doctrine.

For the old timers reading this, you may recall Bobby Vee’s 1960 hit song, “Rubber Ball,” with the sticky refrain: “Rubber Ball, I come bouncin’ back to you.”

Well, a bouncing ball comes to mind—and the Chevron doctrine—when I think of the U.S. Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) long saga dealing with “net neutrality” regulation. Most recently, in December 2017 in its Restoring Internet Freedom Order, the FCC, for the most part, repealed the net neutrality regulations adopted by the Obama Administration’s FCC in 2015. Both the 2015 and 2017 decisions were adopted on 3-2 party-line votes, with the Democrats prevailing in 2015 and the Republicans in 2017.

I acknowledge up front—as I did when I last wrote for The Regulatory Review—that I have long opposed net neutrality regulation in its more stringent forms. So, I am supportive of the Commission’s December 2017 order repealing the public utility-like regulations adopted in 2015. But aside from one’s views regarding the wisdom of net neutrality regulation as a matter of policy, for administrative law scholars, the net neutrality saga promises to be of continuing interest.

Here is the short version—but long enough, I hope, to provoke some thinking about the way forward.

In 2002, confronted with the question of how it should classify the then-emerging broadband Internet access services under the Communications Act of 1934, the FCC determined that Internet access services are “information services,” rather than “telecommunications services.” This decision was consequential because it meant that Internet service providers would be lightly regulated rather than regulated as “telecommunications carriers,” that is, as common carriers under Title II of the Communications Act.

In the 2005 U.S. Supreme Court case, National Cable & Telecommunications Association v. Brand X Internet Services, the Court, in a 5-4 decision, affirmed the FCC’s determination that Internet access services are information services. For present purposes, the main point is that any fair reading of Brand X reveals that Chevron deference, which compels courts to defer to agency actions, so long as they are reasonable, was largely determinative. Under the Chevron doctrine, the Court found the Communications Act’s definitions of “information services” and “telecommunications services” to be ambiguous, and it held that the agency’s interpretation was permissible. Ergo, Chevron deference was granted, and the Commission won.

Now fast forward to 2015. The FCC reverses course, determining that Internet access services are “telecommunications services,” not “information services.” In United States Telecom Association v. FCC, decided in June 2016, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit affirmed the FCC’s changed position, relying largely on Chevron deference and Brand X.

Now fast forward once more, this time to December 2017. The FCC reverts to its original position that Internet access services are information services. This has the effect of repealing the common carrier regime imposed in 2015. Not surprisingly, the FCC did more than nod towards Chevron and Brand X.

This is not to say that the FCC did not also explain in considerable detail why, in its view, a proper interpretation of the Communications Act dictates that Internet access services are information services. It did, and I think the FCC’s current interpretation—the one it defended all the way up to the Supreme Court in Brand X—is the better reading of the statute. But, in any event, the Court has already held that the provisions are ambiguous.

So, it is quite likely that, upon review, the FCC’s most recent interpretation will receive Chevron deference yet again, even if it takes another trip to the Supreme Court. No wonder the “bouncin’ ball” image is stuck in my mind.

I understand, of course, that in Chevron’s domain the “incumbent administration” may change its mind about the interpretation of a statutory provision as long as the construction is permissible. But, is there a point at which courts will say “enough” before stopping the bouncing ball?

There is little doubt in most observers’ minds that if the partisan makeup of the FCC should change after the next election, the “new” FCC would reverse the regulatory classification again to re-impose common carrier regulation on Internet providers. The ball would bounce again.

Despite rumblings of a willingness among some Justices to revisit Chevron, there is nothing in the Supreme Court’s current jurisprudence that leads to a conclusion that yet another reversal—or two—would not be sustained under Chevron. Is there any limit to this back-and-forth?

To be sure, to avoid running afoul of the Administrative Procedure Act’s (APA) reasoned decision-making requirement, the FCC must show that its reversal is not arbitrary and capricious. But the Supreme Court made clear in 2009 in FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc. that the APA makes no distinction “between initial agency action and subsequent action undoing or revising that action.” In short, according to the Court, when changing course, “the agency need not always provide a more detailed justification than what would suffice for a new policy created on a blank slate.”

In other words, the courts are unlikely to stop the net neutrality bouncing ball.

Although I favor the latest FCC decision, it is difficult to argue that this unstable regulatory policy is good for consumers, Internet service providers, or the entire Internet ecosystem. Chevron only comes into play when Congress legislates in an ambiguous way. I say it is time for Congress to end the FCC’s net neutrality saga and legislate unambiguously.