Law and policy experts dissect the challenges created by divergent federal and state laws on marijuana.

“Don’t break out the Cheetos or gold fish too quickly.”

That is what Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper said in 2012 following passage of his state’s voter initiative legalizing recreational use of marijuana. In the intervening years, eight other states and the District of Columbia have legalized cannabis for both recreational and medical use, and a majority of others have legalized it for purely medical use. But as Hickenlooper acknowledged, the federal government still classifies cannabis as a controlled substance, making possession of marijuana for either recreational or medical purposes a federal crime.

At the University of Pennsylvania Law School, a panel of law and policy experts gathered earlier this year to discuss the practical and ethical dilemmas lawyers and other professionals face due to the divergent approaches taken by the federal and state governments on marijuana.

Are duffel bags filled with thousands of dollars in cash really the best way for state-authorized marijuana dispensaries to pay taxes? Are lawyers complicit in federal crimes when helping to set up a client’s state-authorized dispensary? Do doctors risk losing their certification by recommending cannabis to their patients in states where medical use is permitted?

Mark Kleiman, a professor of public policy at New York University’s Marron Institute on Urban Managment, opened the discussion by arguing that, rather than maintaining divergent state and federal policies, federal legalization would probably prove better from the standpoint of reducing the extent of drug abuse. He noted the daunting challenge the federal government faces in enforcing its criminal prohibition on marijuana in the face of relaxed state control. Compared with effectively 50,000 state and local police officers dedicated to drug enforcement, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration employs only 4,000 agents worldwide, he said.

Prof. Mark Kleiman opened the panel discussion about U.S. regulation of marijuana.

Moreover, Kleiman noted that if states continue to drive cannabis policy, it may prove exceedingly difficult for government to collect taxes on these products. A pack of cigarettes—which amounts to about an ounce of tobacco—can cost as much as $10, while an ounce of cannabis typically sells for about $300. Absent a federal decision to tax marijuana uniformly throughout the nation as a legal but regulated product, competitive pressure from interstate smuggling will press the states into a race to the bottom to impose the least restrictive taxes. Already, individuals smuggling tobacco cigarettes from Virginia to New York can profit up to $5.55 a pack due to the tax differential, and one-third to one-half of the New York City market consists of smuggled product.

As long as the federal government maintains its criminal prohibition, businesses that engage in state-authorized marijuana sales will continue to face challenges in complying with banking laws, noted panel member, Peter Conti-Brown, a professor at the Wharton School.

The United States operates under a dual banking system in which there exist both federal- and state- chartered banks. Although federal banks are generally not subject to state supervision, the same cannot be said of state-chartered banks and federal supervision. Since the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913, state-chartered banks have increasingly been required to comply with federal bank regulators and supervisors.

Judge James G. Colins

This dynamic poses challenges for state banks that do business with cannabis companies. The Federal Reserve oversees the process for granting master accounts, which are essential for businesses seeking to provide banking services.

Last year, however, a federal appeals court let stand a lower court’s decision allowing the Federal Reserve to deny a master account request by a credit union dedicated to providing financial services to cannabis businesses—even though the credit union was lawfully chartered by the state of Colorado. The decision only contributed to the overarching confusion about how businesses should navigate the disparate state and federal policies because the three-judge court issued three different opinions in the case, noted Conti-Brown.

Conti-Brown argued that real state experimentation in cannabis policy will only begin once businesses are given banking access—something that has yet to happen.

The Honorable James G. Colins, Senior Judge of the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania, noted that states seeking to experiment will also face questions based on traditional administrative and constitutional law principles, some of which arise under state law.

For example, litigation has erupted over the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s processing of permits to marijuana growers and dispensaries. In a recent lawsuit, businesses that had their permit applications denied by the state claimed that they were deprived of their constitutional due process rights because they were given no opportunity to challenge the denial of their permit application through administrative review.

Collins emphasized that although administrative law principles typically afford deference to agency interpretations, the structuring of regulated marijuana supply networks will necessarily create conflicts that find their way into court.

Overall, the panelists seemed to agree that current trends project indefinite uncertainty for professionals in law, business, and medicine. The changing—and diverging—approaches that state and federal governments have taken seem only to indicate that the contours of cannabis policy will remain murky for some time.

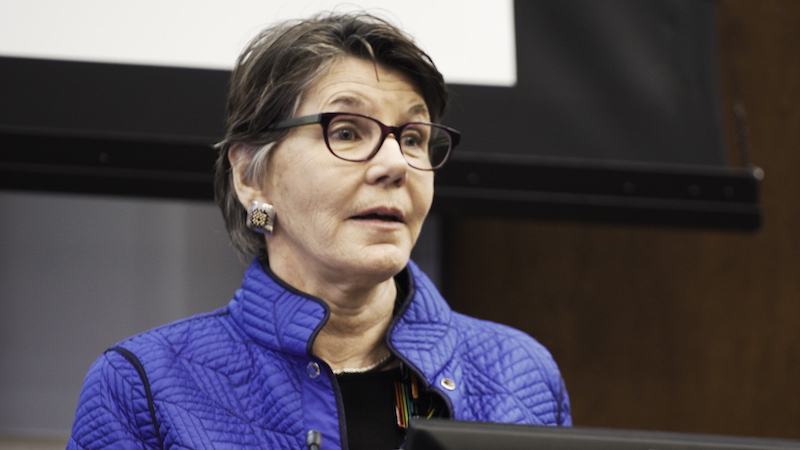

The panel was organized and moderated by Nancy Nord, a former Commissioner of the Consumer Product Safety Commission and a 2017-2018 Distinguished Policy Fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. The event was co-sponsored by the Leo Model Foundation Government Service and Public Affairs Initiative and the Penn Program on Regulation.

Harrison Gunn is a student at University of Pennsylvania Law School and a research assistant for the Penn Program on Regulation.