The Court applies the Chevron test more often than one influential study suggests.

Ten years ago, William Eskridge and Lauren Baer revolutionized the legal discourse surrounding the U.S. Supreme Court’s application of Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council. According to Eskridge and Baer’s empirical study, Chevron’s famous two-step framework—with its reigning status as one of the most cited Supreme Court opinions of all time—is not nearly as influential in the Court’s decision-making process as one might expect. Rather, Eskridge and Baer reported that in over two decades’ worth of cases, the Court failed to apply Chevron in almost 75 percent of cases that were eligible for Chevron deference.

In light of these implications, we decided to take another look at Eskridge and Baer’s prominent finding—but this time using a different methodology. In a forthcoming study in the International Review of Law and Economics, we find that in the majority of cases that Eskridge and Baer examined, Chevron was likely inapplicable. Moreover, even in cases that may have been Chevron-eligible, the Court often did not need to reach the question, or it did apply Chevron in one form or another.

How did we arrive at this contrary result? We applied a different and, we believe, more reliable method. Eskridge and Baer personally coded the Court’s opinions, which required them to make their own judgment as to whether the agency’s interpretation of a statute was eligible for Chevron deference and whether this mattered in the case at hand—a laudable but highly difficult and error-prone task. Instead, we analyzed the litigants’ and Solicitor General’s briefs, “outsourcing” the question of Chevron eligibility to those best positioned, best informed, and best motivated to reach the correct answer.

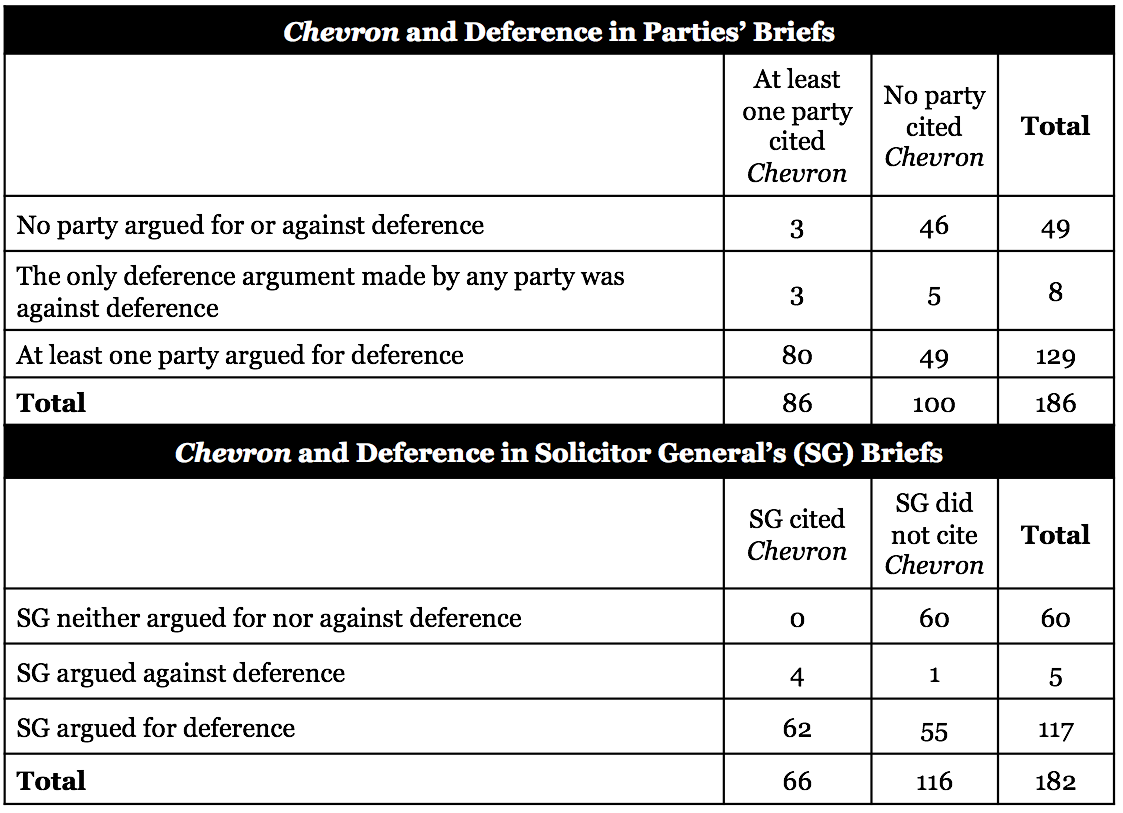

To start, we narrowed in on the 191 “critical cases” where Eskridge and Baer thought the Court should have applied Chevron but failed to do so. We were able to find briefs for 186 of these cases, with the Solicitor General appearing as amicus or on behalf of the petitioner or respondent in 182 of them. We then coded each party’s brief—including the Solicitor General’s amicus brief, where applicable—for two variables: whether the brief cited Chevron, and whether it argued for or against any form of deference to the agency’s interpretation—Chevron, Skidmore, or some other deference regime.

As the tables below illustrate, in over 50 percent of the critical cases, not a single party cited Chevron. Indeed, in 26 percent of critical cases, no party argued for or against deference of any kind. What is more, the Solicitor General did not cite Chevron in 64 percent of its briefs, let alone argue for or against deference in 33 percent of them. To us, this gives rise to a strong inference that over 100 of the “critical cases” were presumptively not Chevron cases. We confirmed this inference through spot-checks involving the careful reading of a handful of the critical cases.

Source: Natalie Salmanowitz & Holger Spamann, Does the Supreme Court Really Not Apply Chevron When It Should? 12 (2018), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3243095.

We then examined a sample of the Court’s opinions in the remaining sets of cases: those where both parties and the Solicitor General as amicus cited Chevron and asked for deference; those without an amicus brief by the Solicitor General in which both parties cited Chevron and asked for deference; and those where at least one party or the Solicitor General as amicus cited Chevron and asked for deference.

We found that in most of these cases, Chevron was either inapplicable to the situation at hand, or the Court decided the case on other grounds, without needing to reach the Chevron question. Plus, if one takes a broad view of what it means to “apply” Chevron—for instance, by deciding the case at Step Two of the Chevron framework without addressing Step One, or addressing the crux of Chevron’s inquiry without explicitly citing the test—the Court can be said to have “applied” Chevron in many of the sampled cases as well.

Our conclusion is that the Supreme Court failed to apply Chevron in only approximately 20 percent of cases where it should have been applied, not the 75 percent that Eskridge and Baer reported. That is to say, the Court does apply Chevron in the majority of cases where it appears that it should.

To be sure, Eskridge and Baer’s study is still a highly important academic feat, especially for its other findings and analyses not discussed here or in our paper. But at the very least, our study casts a different light on the Supreme Court’s application of the Chevron framework, and it suggests that no matter what one thinks of the substantive value of Chevron, it is not a precedent that the Supreme Court consistently ignores or overlooks.