The right-to-work principle protects employee freedom not to subsidize unwanted unions.

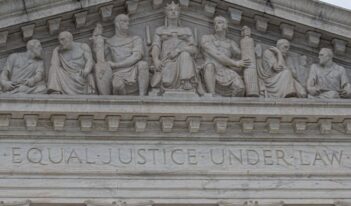

Thomas Jefferson famously said that it is “sinful and tyrannical” for government “to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhors.” That principle is consistent with the guarantees of freedom of speech and association enshrined in the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment. Yet, some federal and state labor laws in this country have long authorized requirements that workers pay union dues as a condition of employment, requirements known as the “union shop” or “agency shop.” Increasingly, however, legislatures and courts are recognizing that workers have a constitutional right to work without being forced to subsidize a union.

Recognizing the inconsistency between forced union fee requirements and worker free choice, in the 1940s state legislatures began enacting what are popularly called right-to-work laws. These statutes simply prohibit requirements that workers pay union dues or fees as a condition of employment. In 1949, in Algoma Plywood & Veneer v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the original National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) did not abrogate the states’ inherent power to enact right-to-work laws. Moreover, in 1947, the U.S. Congress passed the Taft Hartley Act as an amendment to the NLRA, explicitly authorizing state right-to-work laws.

Not surprisingly, unions sued to challenge the constitutionality of right-to-work laws. In 1949, however, the Supreme Court, in Lincoln Federal Labor Union v. Northwestern Iron & Metal, held that state right-to-work laws do not infringe on the freedoms of speech or assembly, deny the right to petition government for a redress of grievances, impair the obligations of pre-existing contracts, or deny equal protection or due process. The Court later reaffirmed those holdings in 2007 in Davenport v. Washington Education Association, citing Lincoln Federal Union when it noted that the state of Washington could eliminate agency fees entirely because “unions have no constitutional entitlement to the fees of nonmember-employees.”

By 2001, 22 states had adopted right-to-work laws. Right-to-work provisions also had been included in the Federal Service Labor-Management Relations Act of 1978 and Postal Reorganization Act of 1970, protecting federal and postal service employees.

Beginning in 2012, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, West Virginia, and Kentucky each adopted right-to-work laws over the course of five years. Kentucky became the 27th right-to-work state at the beginning of 2017, when Governor Matthew Bevin (R) signed a right-to-work bill passed by the Kentucky General Assembly. The General Assembly passed the bill using its emergency powers, declaring the legislation “critical to the economy and citizens of Kentucky to attract new business and investment into the Commonwealth as soon as possible.”

Despite the Supreme Court precedents in Lincoln Federal Labor Union and Davenport, unions have challenged each of the new state right-to-work laws. In these suits, the courts have considered two new legal arguments that right-to-work laws might be unconstitutional: namely, that those laws are preempted by the NLRA and thus violate the Supremacy Clause if they prohibit the forced collection of fees for collective bargaining and contract administration, and that those laws deprive unions of property, in the form of the costs of representing nonmembers when the unions become “exclusive representatives,” without just compensation in violation of the Constitution’s Takings Clause.

Appellate courts have rejected these two arguments every time challengers have raised them. The preemption argument has failed because Algoma Plywood and the NLRA leave the states free to enact laws prohibiting all forced union fees. Courts have rejected the takings argument because unions volunteer for the privilege and power of exclusive bargaining and benefit from that extraordinary status, which deprives workers of the right to deal themselves with their employer concerning their conditions of employment.

In contrast to the 27 right-to-work states, other states have enacted legislation requiring workers to pay union fees, either as a condition of public employment or to receive state funding for working as home-or child-care providers. Forced fees for public employees were challenged as violating the First Amendment in the 1977 Supreme Court case Abood v. Detroit Board of Education. The Court held that contributions could constitutionally be compelled for “collective bargaining activities” but not for political and ideological purposes.

But when the issue of forced fees again reached the Supreme Court in 2014, this time in a case concerning home-care providers, the Court criticized the Abood Court’s analysis as “questionable on several grounds” and refused to apply Abood to home-care providers who are not public employees. Instead, the Court applied “the bedrock principle” that “no person in this country may be compelled to subsidize speech by a third party that he or she does not wish to support.” Applying this right-to-work principle, the Court found that forcing home-care providers to pay union fees violated the First Amendment.

The issue reached the Supreme Court again in Janus v. American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, decided in 2018. This time the plaintiffs were public employees forced to pay union fees as a condition of employment. The decision recognized that when a union deals with a government employer their actions are inherently political, because they affect the use of public resources and may demand public policy decisions. For this reason, the Court held “that public-sector agency-shop arrangements violate the First Amendment, and Abood erred in concluding otherwise.”

In Janus, the Court overruled Abood and held that “states and public-sector unions may no longer extract agency fees from non-consenting employees.” Janus recognized the First Amendment as a right-to-work provision built into the Constitution for all public employees.

Janus also supports the constitutionality of state right-to-work laws. Kentucky’s highest court upheld that state’s right-to-work law after Janus was decided. Significantly, the Kentucky court reasoned that Janus “conclusively refutes” unions’ Takings Clause “claim that they will be compelled to provide services without compensation.”

After Janus then, all public employees nationwide have right-to-work protections for the foreseeable future as a matter of federal constitutional law. Whether additional states enact right-to-work laws for private-sector employees is a political question, depending on election results in each of the states that do not have such laws today. However, as the uniform appellate court precedents, including Janus, demonstrate, future union legal challenges to those laws are unlikely to succeed.

This essay is part of a nine-part series, entitled The Future of Workplace Regulation.