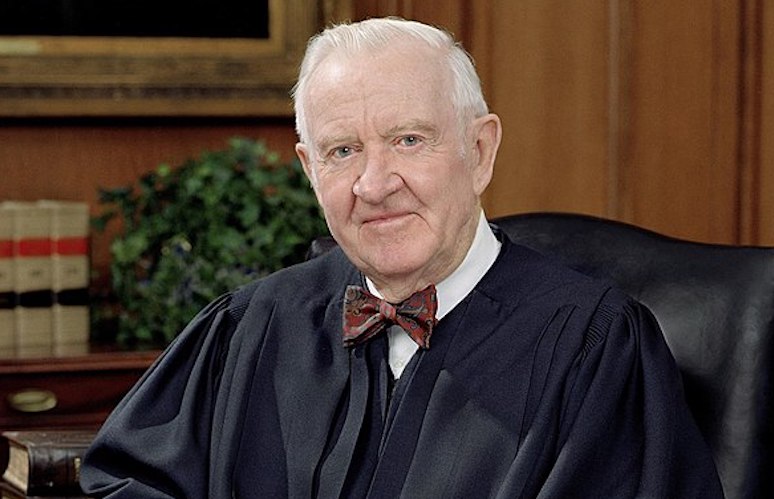

The late justice’s opinion in Chevron v. NRDC has greatly shaped judicial reasoning about administrative law.

Justice Stevens’s 1984 opinion in Chevron v. NRDC may be completely unknown to most members of the public. But that opinion has had an enormous impact for the last thirty-five years in terms of how courts reason about their role in overseeing government. Indeed, in an interview while he was still on the bench, Justice Stevens himself referred to his approach to statutory interpretation, presumably including Chevron, as among his most significant judicial achievements. I think he was right.

In Chevron, the key issue centered on a provision in the Clean Air Act authorizing the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate sources of pollution. But the statute did not define what constitutes a “source.” EPA originally considered each and every smokestack or pipe at an industrial facility to be a “source,” and it regulated each of them separately. But during the Reagan Administration, EPA (then headed by Justice Neil Gorsuch’s mother) decided to interpret “source” more flexibly so as to encompass an entire facility with all its individual smokestacks and pipes—and then essentially to apply an overall facility-wide limit on air pollution, rather than a set of individual, pipe-by-pipe standards.

Justice Stevens’s unanimous decision framed the legal question in terms of the comparative roles for the courts versus agencies: When a federal agency adopts an interpretation of a statutory term such as “source,” what weight, if any, ought courts give to a considered judgment made by the agency, another duly authorized governmental body? Stevens’s opinion answered that question by articulating a two-step framework that nearly every judge now invokes when approaching the task of statutory interpretation in the context of an administrative law dispute.

Chevron held that courts should first ask if the statutory language at issue is clear, and, if it is, the court must apply that clear meaning regardless of the agency’s position. But when a statute is ambiguous, the courts may proceed to imply that Congress has delegated to the agency the authority to resolve the ambiguity and then must accept the agency’s interpretation as long as it is not unreasonable. EPA prevailed in Chevron because the Clean Air Act never made it clear whether a “source” meant an individual smokestack or an entire facility, and the Court held that it was proper to defer to the agency’s reasonable facility-wide interpretation.

Since 1984, lower courts, the Supreme Court, and virtually every administrative law scholar in the country has grappled with the meaning, scope, and application of the Chevron doctrine. To understand Chevron’s significance, consider that it has garnered more than 11,000 citations, over five times the number of citations that some of the most significant, salient, and consequential constitutional law decisions have had, including Marbury v. Madison, Brown v. Board of Education, and Roe v. Wade.

Americans now live and work under administrative government, where most law is governed by statutes and implemented by administrative agencies. Justice Stevens’s opinion in Chevron has provided what is probably the most important framework by which lawyers and judges understand what the rule of law means in the administrative state. Justice Stevens did not think his opinion’s framework was at all original, viewing it modestly as a distillation of prevailing law reflected in many prior decisions of the Supreme Court. I think he was right about that. But what Justice Stevens could rightly claim credit for was his opinion’s elegance and clarity, which is undoubtedly the major reason that Chevron has been so widely cited and discussed.

Today, thirty-five years later, Justice Stevens’ Chevron opinion remains the authoritative statement on statutory interpretation in the administrative state. But Chevron is also seen as increasingly controversial, especially because several current members of the Court (including Justice Gorsuch) have questioned its call for judicial deference to administrative agencies. As a result, if the general public has not heard of Chevron yet, it may well hear more about it in the coming years, should the Court decide to revisit its approach to statutory interpretation.

Whatever Chevron’s precise future, Justice Stevens was almost certainly right to suggest that this decision was among his most significant judicial accomplishments. As I have written elsewhere, “for as long as Congress continues to give agencies discretion in how they administer statutes, and as long as courts continue to review agency actions for compliance with law, judges will continue to confront the same questions presented by Chevron’s two steps.” In one masterfully written opinion, with two beguiling steps, Justice Stevens encapsulated and clarified, and also set the terms of debate for, much of administrative law.

I salute Justice Stevens’ service and mourn his passing, and I also am confident in predicting that the nation’s judiciary and academy will remain engaged with and inspired by his legal craftsmanship long into the future.