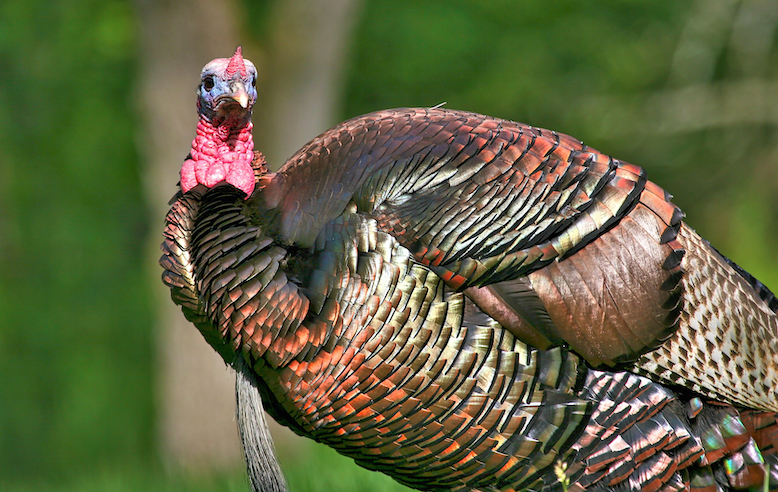

Regulation, combined with other efforts, has successfully repopulated wild turkeys in the United States.

Each November, families gather across the United States for the Thanksgiving holiday and collectively they consume about 45 million turkeys. At the same time, another approximately 7 million wild turkeys roam free across the nation. Some of these wild turkeys have appeared to adapt to the humans that surround them, at times befriending local mail carriers and even learning to knock on neighbors’ front doors in search of a snack.

But just a century ago, the fate of the wild turkey was dire and its future uncertain.

By the 1930s, the wild turkey population had plummeted to its lowest levels ever—about just 30,000 birds in total—a dramatic decline from the 10 million or more turkeys that roamed North America prior to the arrival of Europeans.

The wild turkey population started its decline when early settlers to North America began to hunt them and started to clear forest land for agriculture. The decline only accelerated with Europeans’ westward expansion, the growing agricultural industry, and the construction of railroads. By 1920, 18 of the 39 states that had constituted the wild turkey’s historical habitat had completely lost their wild turkey populations.

Attempts to recoup the wild turkey population began in some states in the 1930s, largely under pressure from hunting and sporting groups. As early as 1929, the Virginia Game Commission—now the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries—began a program in which a total of 22,000 turkeys were raised on game farms and then released into the wild. Similarly, in Pennsylvania, from 1930 to 1980 the state’s Game Commission released more than 200,000 game-farm turkeys into the wild.

But in these states and others, the game-farm method failed because a turkey’s ability to survive in the wild is largely learned from its mother.

During the 1950s, a discovery made by South Carolina’s Herman “Duff” Holbrook would have a profound impact on the conservation of wild turkeys. When Holbrook used a net cannon—previously used only on waterfowl—to trap wild turkeys and later release them in new natural habitat, he experienced success. Soon, other states began “trap and transfer” programs with great success.

From West Virginia, to New York, and Missouri, trap and transfer efforts have helped reintroduce over 200,000 turkeys into habitats in 48 states. Many of these reestablishment efforts have been coordinated by the National Wild Turkey Federation—a non-profit organization that focuses on wild turkey conservation efforts across North America.

In addition to trap and transfer initiatives, land management efforts have helped reestablish wild turkey populations. The U.S. Department of Agriculture recommends specific regional plants that can be grown to maintain current levels of turkey populations. State agencies provide seed and planting equipment to those who will propagate turkey habitat.

Hunting regulations have also helped maintain current populations of wild turkeys. Although the birds are considered to be “valuable game species,” hunters looking to put a turkey on the table are subject to state and federal regulations.

Most states have established a general regulatory framework and a corresponding government agency to oversee hunting. State regulations typically require hunters to be licensed and obtain permits. States have also established bag limits to restrict the number of birds a single person can hunt, and they have created specific “turkey seasons” when the birds can be hunted––typically in the fall and spring.

Although regulations have been effective at helping to rebuild the turkey population, not everyone is happy to have the birds roaming free. Wild turkeys have been known to destroy agricultural crops and can cause damage to private property when they enter suburban areas. Wild turkeys can also be aggressive, especially during their mating seasons. The media have reported numerous incidents of turkeys attacking people in recent years. Turkeys have also caused fatal car accidents when they wander into the streets.

The restoration of the wild turkey population does bring certain challenges to those who live near their habitat, but it also represents one of the United States’ notable conservation success stories. Public and private reestablishment efforts have helped assure that wild turkeys still have a home this Thanksgiving—just not on most families’ dinner table.