Decades-long efforts in Vietnam to improve local governance have kept recorded coronavirus cases low.

Vietnam, the fifteenth-most populous country in the world, with 96 million people, has reported a mere 328 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and zero deaths.

Commentators have attributed Vietnam’s effective response to a host of factors, including the government’s early actions to close schools and borders, extensive contact tracing and mass quarantine, and past experience with SARS. A puzzle, however, still remains: What enables compliance with these restrictive measures in a single-party state that is otherwise notorious for struggling to enforce rules? Giving credit mainly to Vietnam’s authoritarian toolkit risks missing a more salient narrative about Vietnam’s decades-long effort to improve governance and responsiveness at local levels.

In this essay, I highlight two particular features of Vietnam’s regulatory narrative: mass mobilization of civil society, and an upward trend in transparency of Vietnam’s party-state. Enabled by improving governance and effective local-central coordination, these two features play critical roles in the implementation of strong-armed, controversial measures at local levels. I then turn to the question of whether the low numbers for reported coronavirus cases and fatalities are credible. Although information flows are generally more robust in democracies than in non-democratic regimes, transparency efforts have mitigated skepticism toward the party-state’s COVID-19 reporting.

Vietnam’s Regulatory Responses. On January 28, 2020—six days after Vietnam’s first reported case of COVID-19—Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc issued a directive declaring that “fighting the epidemic is fighting the enemy” (“chống dịch như chống giặc”). Vietnam was the second country after China affected by SARS in 2003. This made Vietnam wary of developments in Wuhan, especially as the Lunar New Year triggered waves of cross-border travel by migrant workers and tourists. Referred to as the “Tet Offensive of 2020,” the call to arms against COVID-19 evoked an ethos of patriotism and sacrifice that characterized the country’s long decades of warfare. Without South Korea’s widespread testing or Taiwan’s highly developed contact tracing system, Vietnam’s so-called “low-cost” method hinged on the party-state’s ability to track and quarantine potentially infectious individuals before COVID-19’s spread could overwhelm the country’s already-crowded hospitals.

In praising Vietnam’s actions, the World Economic Forum noted the government’s “proactive efforts,” including early school closures, mass quarantines, and border closings. Vietnam was the second country after China to implement forced quarantine at both the local and national level. Provincial authorities were allowed to seal off whole geographic areas and quarantine travelers from other provinces. Officials could send international and domestic travelers, suspected of carrying the virus, to government-run military camps overseen by army personnel and provided free of charge. By the end of March, the government had quarantined nearly 50,000 people, half of whom were held at state-run facilities.

The government recently issued a 15-day nationwide social distancing order and imposed fines on those who ventured outside without masks. A recent Supreme People’s Court guidance letter interpreted the 2015 Penal Code to include violations of quarantine regulations and business suspension orders. The Court also deemed the spreading of misinformation related to the pandemic a criminal offense. The Ministry of Public Security’s local police offices have started prosecuting cases on allegations of fake new dissemination and quarantine violations. In anticipation of looming economic effects, Prime Minister Phúc reiterated that Vietnam must accept “economic sacrifice” to save lives.

Vietnam’s regulatory response to COVID-19 centers around a mobilization campaign reminiscent of wartime exigency. Similar to China’s response, Vietnam encouraged individuals and households to actively monitor quarantine violations. Neighborhood committees (tổ dân phố)—a staple of socialist grassroots administration—act as a combination of state agents and community organizers. Composed usually of local Communist Party bureaucrats and retired army personnel, these committees have their members knock on doors to relay official policies, explain social distancing, collect households’ health and travel history, and take people’s temperatures.

Mass civic organizations, once suffering from declining budgets, have regained new purposes through anti-coronavirus fundraising campaigns and community outreach. Notably, the Vietnamese leadership has called for unity and support from overseas Vietnamese immigrants—signaling the government’s view that the protection of national health should transcend political and ideological differences.

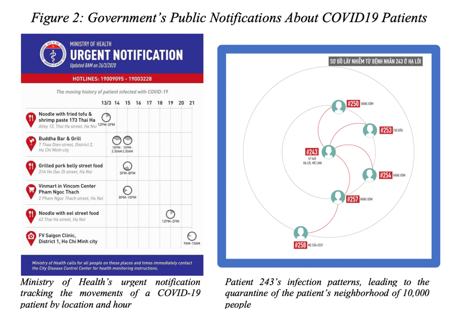

A second critical aspect of Vietnam’s response to COVID-19 is an upward trend in transparency enabled by decades-long engagement in better governance. The Vietnamese leadership appears to have learned from China’s cover-up debacle by taking a more open approach. Notwithstanding its record of internet censoring, the government has leaned heavily on social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter to keep citizens up to date on rapidly changing regulations and social programs related to the pandemic. The Office of the Government’s Facebook portal, for example, regularly publishes information about individual COVID-19 patients, including their initials, general locations, detailed timelines of their travels and whereabouts, actions taken to keep them isolated, and updates on their health.

When news broke in early March about “Patient 17”—a positive case after over two weeks with no new infections nationwide—news outlets blasted videos and images of government trucks spraying disinfectants and closing down the patient’s neighborhood. These information campaigns help facilitate contact tracing and boost public confidence in the party-state’s capacity. Vietnamese citizens, however, have expressed divided opinions and concerns about privacy violations, bullying, and discrimination, especially when patients belong to vulnerable groups.

The Politics of Numbers. How credible is Vietnam’s astonishingly low number of coronavirus cases? Scholars have long documented the politics of information and indicators, especially concerning data manipulation in authoritarian regimes. Undercounts of COVID-19 cases—due to testing unavailability, the difficulty in detecting asymptomatic carriers, and challenges to identifying non-hospitalized deaths—is a global concern spanning continents and political regimes. In general, information suppression is more difficult in democracies, especially those with a functioning and vibrant press. For skeptical watchers, Vietnam’s measures to stifle freedom of speech in recent years, the latest being a controversial cybersecurity law, have cast a shadow on its credibility in an otherwise impressive and admirable effort to combat the epidemic.

Transparency efforts have mitigated skepticism toward the party-state’s COVID-19 reporting. The Ministry of Health’s online disclosure of all reported cases has enabled deeper analysis by data scientists and bloggers and gained endorsement from public health experts. When a patient who tested positive for COVID-19 died from liver failure, the government used its Facebook portal to publicly discuss its reasoning for not counting his death—the patient’s advanced liver dysfunction and a series of negative COVID-19 tests premortem. Although under-counting is possible, public disclosures open space for discussion and allow for corrections if needed.

Furthermore, Vietnam’s online network of activists, although still critical of privacy violations and the lack of freedom of speech, have not sounded the alarm on widespread fatalities or cover-ups. With nearly 70 percent of its population online, Vietnam has one of the highest internet penetration rates in the world and is ranked seventh in terms of the number of Facebook users. Political activists have turned to Facebook as a main platform to voice opinions and provide counter-narratives not available in state-controlled media outlets, including in sensitive matters such as police violence over land rights, protests over the South China Sea dispute, and toxic spills causing a devastating environmental disaster. In the current situation, activists are an important, even if silent, source of non-state information that suggests that under-reporting, if present, is unlikely to be substantial.

Conclusion. As we collectively learn from the global efforts to combat the pandemic, Vietnam’s story moves beyond the simple distinction of regime type to challenge us to think more deeply about state capacity within all forms of government.

Vietnam historian Christopher Goscha described the country’s ethos as akin to a mid-empire—once shackled under colonial rules but also proactive in pushing its own geopolitical ambitions. His description is even more apt in the current time. Deemed a favorite “China plus one” destination in the race to diversify global supply chains, Vietnam has already exported half a million hazmat suits to the United States and donated millions of face masks to countries such as Cambodia and those in the European Union. It is the incoming chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations for 2020 and will join the United Nations Security Council as a non-permanent member in 2021. As General Secretary and President Nguyen Phu Trong noted, Vietnam’s performance in combatting COVID-19 is linked to its regional and international standing.

Although Vietnam has done an impressive job managing the crisis, its credibility at home and abroad depends on its continued transparency and, in the long run, facilitation of a robust civil society.

The author thanks Edmund Malesky and Le Nguyen Duy Hau for their comments on this essay.

This essay is part of an ongoing series, entitled Comparing Nations’ Responses to COVID-19.