The government must recognize constitutional property and free speech rights in communications law and policy.

The U.S. Constitution is the foundational source for authorizing all legitimate government activity and is thus the source for restraining illegitimate activity. The realm of communications law and policy, in some instances, is still beset by government regulatory controls—including public utility-like regulation of telecommunications carriers and programming content mandates for broadcasters and cable operators, among other controls—that originally were designed to address 20th century monopoly-like marketplace conditions.

Such government dictates at least strain certain constitutional values, if not violate constitutional requirements.

But the 21st century communications marketplace—which is enabled by digital technologies and internet protocol-based broadband services delivered over wired, wireless, satellite, and hybrid delivery platforms—is vibrant and competitive. As a result, the tension between many regulatory controls on communications services and constitutional requirements is much greater than ever before. Today’s dynamic marketplace calls for a modernized communications law and policy that is consistent not only with technological advances but with a proper understanding of the U.S. Constitution.

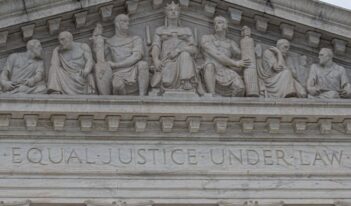

The Constitution embodies foundational principles that the U.S. Congress and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) ought to follow when establishing and administering federal communications law and policy. These principles include protection of private property, freedom of contract, and freedom of speech, as well as support for private enterprise and an open interstate commercial marketplace.

The Constitution’s framers understood that one of the primary purposes of government is to protect rights to keep, use, and acquire property. Different constitutional provisions, including the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, help secure private property rights. As the framers also understood, private property ownership is not only a matter of natural right, but it also encourages productive uses of resources. Property owners are more likely to cultivate and seek the most beneficial uses of property because they own it.

The federal regulation of communications services implicates private property in many ways. For example, now-repealed net neutrality restrictions—that effectively imposed rate controls or required capacity set-asides for carrying traffic that broadband internet service providers might prefer not to carry—deprive those internet service providers of control over their own property. And legacy rules that impose program carriage and other access requirements on cable and satellite operators limit their property rights.

Furthermore, in the framers’ understanding, free speech is a natural right. Indeed, the First Amendment protects freedom of speech from government interference. But it does not authorize government to equalize speech or enable more speech by one party at the expense of another party’s rights. And because communications technologies and services are widely used for distributing speech, they should receive First Amendment free speech protections.

Historically, an inherent tension exists between federal regulation of communications services and the First Amendment rights of providers of those services. Regulation of broadcast and cable services has dictated what broadcast and cable service providers may or may not say, as well as content they are required to carry and the terms of such content. These regulations negate and undermine private editorial decisions.

For example, “must carry” regulation requires cable and satellite operators that offer multichannel video subscription services to carry content not of their own choosing. Those requirements abridge these service providers’ editorial speech rights to determine content programming and channel lineup placement. Previous iterations of net neutrality regulation have also threatened the free speech rights of broadband internet service providers by requiring those providers to carry speech content that they might prefer not to carry.

Although the Constitution does not formally institute or require a particular economic system, the framers’ philosophical commitments to private property rights, reflected in several provisions of the Constitution, serve as essential building blocks to support a free market enterprise that facilitates individual liberty and human flourishing.

Importantly, the framers and later generations’ presumptive favoring of private property ownership has proved congenial to private enterprise, including in the communications services market. Under private sector leadership, broadband internet service providers successfully have deployed wireline and wireless services. For example, between 2011 and 2019, wireless network investment totaled $261 billion. Between 1996 and 2019, capital expenditures by fixed wireline broadband providers totaled over $1.7 trillion.

Government should not seek to compete with private market providers. For example, the U.S. Department of Defense’s recent proposal to enter the commercial 5G wireless market would harm taxpayers. Defense Department market entry could also undermine billions in private capital investment and encourage the government to privilege itself over private sector providers. The government should avoid such entry, absent some demonstrable, compelling national security interest that private sector competition cannot satisfy.

Similar fiscal and policy problems arise from state and local government efforts to own and operate broadband internet networks in competition with private market providers. And as a matter of constitutional federalism, neither Congress nor the FCC should interfere with state laws or state-level safeguards concerning municipal broadband projects.

In addition to the creation of an environment conducive to fostering private enterprise, the framers established a system for uniform federal regulation to ensure an open interstate marketplace. The Constitution’s Commerce Clause grants Congress the power to regulate commerce among the states. Exercise of that authority, in conjunction with the Supremacy Clause, preempts state and local regulations that conflict with nationwide commercial policy objectives. The framers and other early generations of American leaders and jurists recognized federal preemption’s purpose in eliminating state-level protectionist barriers to interstate commerce.

States, however, retain significant constitutionally protected authority within their jurisdictions. States have approval authority over the siting of cell towers, antennas, and other wireless network infrastructure. But federal law even imposes limits here. Wireless networks are channels of interstate commerce, and the Communications Act bars state regulatory actions that effectively prohibit the siting or modification of cell sites. The FCC has enforced those limits, and courts have largely upheld the FCC’s preemptive authority in this area.

Maintaining exclusive federal jurisdiction is critically important for broadband internet access services. Broadband internet networks routinely send and receive data traffic from interstate and foreign websites and hosts. As a practical matter, intrastate aspects of their operations cannot be detected and separated. State regulation of broadband networks therefore unavoidably burdens interstate commerce.

Under the Communications Act, information services—electronic services that, among other functions, generate, process, and store data—are jurisdictionally interstate. The FCC has shared this view going back to at least its 2002 cable modem order. Indeed, the jurisdictional status of today’s information services, which were called enhanced services prior to the Telecommunications Act of 1996, as interstate traces directly back to the FCC’s seminal Computer II decisions in the early 1980s.

The clash between the light-touch, free-market oriented federal policy on interstate information services and state net neutrality laws that purport to impose public utility regulation on those same services is evident.

Congress and the FCC should consider the constitutional backdrop of Commerce Clause and Supremacy Clause jurisprudence and maintain a uniform regulatory policy for broadband internet services. Such an approach—which has been in place since the adoption of the 2017 “Restoring Internet Freedom” order—will promote the investment and innovation that is essential to the creation and implementation of robust private sector internet networks.

Members of Congress swear an oath to uphold the Constitution. Accordingly, they should reject legislation that jeopardizes private property and free speech rights that are foundational to free enterprise and free markets. So too should FCC commissioners and other federal officials—who swear the same constitutional oath—strive to avoid even potential infringement of constitutional rights.