Science is vital for effective risk governance but so too is public engagement.

For every eight fatal victims of COVID-19 worldwide, one is Brazilian.

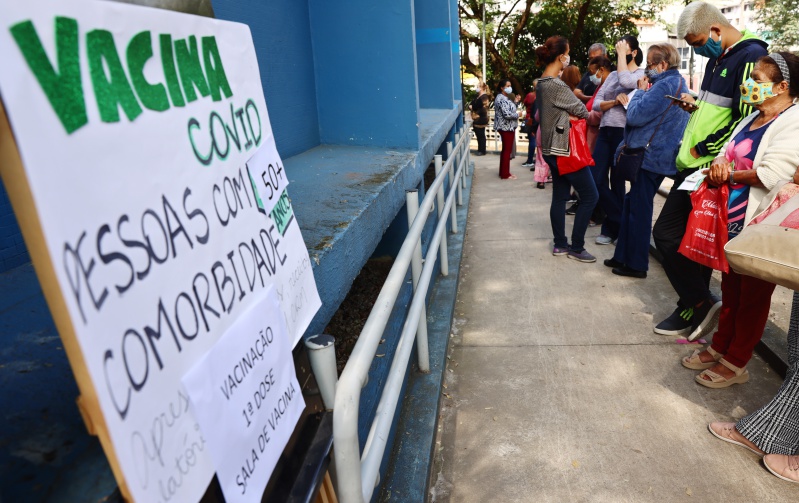

Brazil is second in the world in total deaths from COVID-19, behind only the United States. In the United States, however, the death curve has been falling as more of its population is vaccinated, while Brazil still suffers from a lack of vaccines.

Brazil’s ability to combat the deadly virus is hampered by extreme political and social polarization. At the same time that many governors and mayors have imposed protective restrictions on economic activities, President Jair Bolsonaro claims that the real threat comes from the economic disruption that the pandemic can cause. He has mocked the efficacy of vaccines and ignored the use of masks when appearing in several large public events. And he is not alone. Throughout Brazil’s major cities, “it is easy to find maskless crowds walking the streets, conversing in close quarters.”

In Brazil, as elsewhere in the world, a key question arises: How can regulatory remedies aimed at combatting public health risks such as COVID-19 be made more effective? The answer depends only in part on scientific expertise. It is also vital to promote greater public engagement in the regulatory process so as to reinforce the legitimacy of risk regulation and thereby promote greater compliance with rules aimed at promoting public health.

Since the 1990s, risk regulation has emerged as a new paradigm alongside traditional economic regulation. Indeed, the proliferation of risks produced by technological progress has resulted in a redefinition of the responsibilities of economic actors, civil society, and especially government, which in many countries has become the ultimate risk manager.

As noted by legal scholar Cary Coglianese of the University of Pennsylvania, “the level of deterrence provided by tort liability will often prove to be much lower than is socially desirable,” which makes regulation “necessary to supplement, or even replace, common law liability.” In this context, regulation has become increasingly shaped by the risks generated by certain activities.

According to regulatory scholar Julia Black of the London School of Economics and Political Science, “risk plays four main roles in regulation: providing an object of regulation; justifying regulation; constituting and framing regulatory organizations and regulatory procedures; and framing accountability relationships.” Ultimately, regulation “can be seen as being inherently about the control of risks,” which makes it possible to link together two prevailing academic ideas about the emergence of both a risk society and a regulatory state.

Dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic can be considered a case of risk regulation. According to legal scholar Alberto Alemanno of HEC Paris, COVID-19 reveals “the difficult interplay between science and politics, as well as between democracy and evidence-based public policy, when responding to risk through risk management.” It also shows, according to Alemanno, “the need to factor in people’s perceptions of risk and responses to it, especially when communicating about it.”

In Brazil, the COVID-19 pandemic has placed science at the center of public debate, with differing views about its importance as a factor that legitimizes the government as a risk manager. For example, Law No. 13,979, enacted in 2020 at the beginning of the pandemic in Brazil, allowed government authorities to adopt a series of invasive and restrictive measures, including compulsory vaccination, as long as these measures are based “on scientific evidence,” among other factors.

The Brazilian Supreme Court, in reviewing the constitutionality of Law No. 13979, decided that compulsory vaccination cannot mean forced vaccination, as any individual must be able to refuse to be vaccinated. Nonetheless, the government can implement indirect measures, such as restrictions on the exercise of certain activities or the frequency of certain places, provided that such restrictions are based “on scientific evidence.”

Focusing on the science, however, may not be enough to provide policymakers with a stable basis for risk decision-making. The risk regulation literature makes clear that, historically, scientific risk assessment has had its critics. Moreover, as Cary Coglianese has observed, risk assessment is different from risk management: “While risk assessment is … conventionally understood to be predominantly (but not exclusively) a scientific undertaking, risk management decisions, including the selection of regulatory standards, require making value judgments that extend beyond the scope of science.”

Despite the extreme importance of science in the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic, its limitations can be identified in some situations. For example, the World Health Organization, which is supposed to coordinate the global response and produce a common scientific basis for the risks surrounding COVID-19, was severely criticized for its slow performance at the beginning of the pandemic, and these criticisms have the potential to undermine the WHO’s scientific character. The experience with COVID-19 suggests that regulators must focus on considerations other than just science when governing risks.

How lay people think about and respond to risk is particularly important. Only by understanding the ways that the public processes risk information can regulators and other officials expect to improve the communication of risks. As psychologist Paul Slovic of the University of Oregon argues, “those who promote and regulate health and safety need to understand how people think about and respond to risk. Without such understanding, well-intended policies may be ineffective.”

The psychological approach to risk seeks to assess the different cognitive perceptions and preferences related to risks, demonstrating that individuals display biases in their behavior when faced with different risks. Slovic argues that “many of the qualitative risk characteristics are correlated with each other, across a wide range of hazards.” For instance, “hazards judged to be ‘voluntary’ tend also to be judged as ‘controllable,’” though “hazards whose adverse effects are delayed tend to be seen as posing risks that are not well known.”

Slovic concludes that lay people’s basic conceptualization of risk “reflects legitimate concerns that are typically omitted from expert risk assessments,” which requires that both communication and risk management “are structured as a two-way process,” in which each side—expert and public—“has something valid to contribute. Each side must respect the insights and intelligence of the other.”

It should be clear that to improve the efficacy of regulatory remedies, no one doubts that science is needed to identify and assess the nature of the risks surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic. Science, though, has its limitations too. Any successful effort to combat the COVID-19 pandemic necessitates that regulators also understand how the public perceives, assesses, and responds to risk. The limits of science become even more evident in situations, such as with the initial stage of a pandemic, where scientific data are scarce but the demand for answers is great.

Brazilian policymakers and regulators should consider combining the use of science with efforts to promote public participation and accountability. A risk governance model targeted at COVID-19 needs to promote greater public engagement, which has the potential to reinforce the legitimacy of the risk regulation regime and, consequently, generate greater adherence to behavioral guidelines aimed at tackling the COVID-19 pandemic. One starting point along these lines would be for the several national, state, and municipal committees created to combat COVID-19 to provide greater openness to civil society.