HIPAA consistently falls behind health and wellness technology, jeopardizing individuals’ data privacy.

Limited by its antecedents and its own genesis, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) has spent a quarter-century playing catch-up with technologies that intersect with health care and wellness.

Prior to the mislabeled HIPAA privacy rule, the common law required confidentiality of health care data. Confidentiality is not privacy; it protects only the disclosure of data, not its collection. In the middle of the 20th century the common law of confidentiality took the stage, not due to some nascent sense that personal health data deserved protection, but because clinical and public health needed persons to disclose health information to facilitate their, respectively, narrow and broad missions.

Those clinical and public health priorities explain much of HIPAA’s structure. For example, HIPAA’s protective aspects frequently are subordinate to its disclosure carve outs. HIPAA’s confidentiality roots not only have limited its reach to protecting against disclosure but also have required a traditional health care relationship, such as between a physician and patient—that is, between the data subject and the data custodian.

In contrast, information technologies today enable far more promiscuous behaviors, with the data subject frequently unaware of the identity of the custodian.

The HIPAA privacy rule is wordy and complicated, bereft of general principles that educate the reader or aid interpretation. It is hardly surprising, then, that over the decades people have misunderstood HIPAA. It has been cited as a legal basis to support all sorts of indefensible positions. Recently, for example, some commentators have taken the ludicrous position that HIPAA makes it unlawful to inquire into a person’s vaccination status!

More broadly, providers have cited the HIPAA privacy rule to justify “information blocking,” aiming to keep what they view as proprietary information within network, to keep health data out of the hands of “big tech,” or—perversely because of HIPAA’s own access rules—refusing patient requests for their own records. Only recently has the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) proposed changes to the rule to improve patient access and coordination of care among providers.

These issues, however, pale in comparison to HIPAA’s greatest limitation. Simply put, HIPAA does not protect all health data. Rather, it places restrictions on the disclosure of some health information by traditional health care providers and health insurers. As more health data are generated outside of traditional health care, HIPAA’s protective impact is shrinking, which places it at a growing disadvantage in a world of digital health.

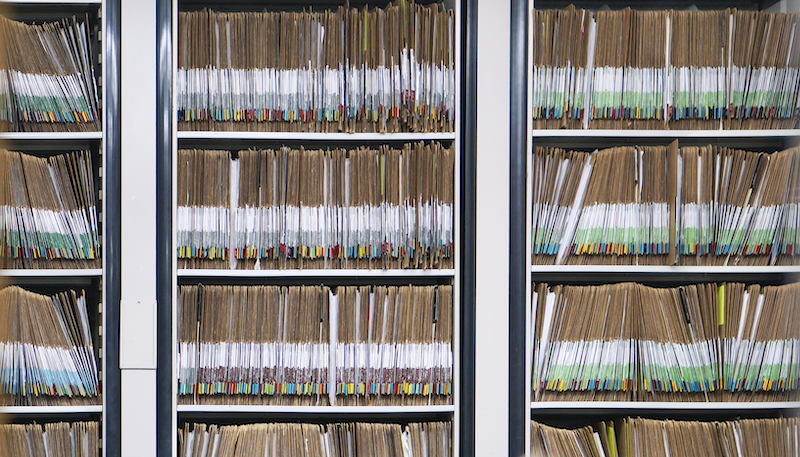

Born into a medical records and reimbursement world that was a grim celebration of filing cabinets stuffed with paper and the staccato rhythm of fax machines, the architects of the HIPAA privacy rule at HHS understood their work to be part of an effort to nudge health care stakeholders toward “administrative simplification,” or more efficient technological communication.

The mandate to create better technological communication comes from Title II of HIPAA, which also provides HHS’s privacy and security rulemaking authority. HHS, however, may not have foreseen the complex race with information technology that unfolded over the last quarter-century, a race that increasingly has seen HIPAA’s impact marginalized.

HIPAA was enacted not long after the creation of the internet, but before the internet became as popular or used for commercial purposes as it is today. Indeed, this was a time when only a small number of providers used any information technologies. HIPAA transaction rules forced health care insurers and providers to adopt e-commerce tools, stuffing electronic “envelopes” with patient information necessary to complete reimbursement and related transactions, while the HIPAA privacy rule provided a legal regime to protect against the disclosure of this newly portable health information.

As providers became more connected and as policymakers began to promote specific technologies, such as electric health records, it became obvious that HIPAA privacy was lagging behind. Soon, and with the financial encouragement of the federal government, the “meaningful use” subsidy program dramatically increased the number of electric health records.

Scholars have spilled much critical ink on the meaningful use program. What is clear, however, is that U.S. health care, willingly or not, quickly became the collector and custodian of billions of patient health data points. Coincident with the subsidy program, a few years after the electronic health records revolution began, the HITECH Act of 2009 reacted with some strengthened HIPAA protections, such as limitations on the sale of protected health information, breach notifications, and more robust enforcement.

While chasing one technology—electronic health data collection—HIPAA was unprepared for the next major revolution—digital health or wellness data being generated outside of the health care system by patient–consumers using apps on phones and wearables, or by the myriad of “smart” devices in homes and automobiles, known collectively as the “internet of things.” The data collectors or custodians of these data are seldom traditional health care providers, insurers, or their business associates. As a result, HIPAA protections simply do not apply to these data.

Meanwhile, corporate America became acutely aware of the value of health data. Individuals and companies building health care artificial intelligence tools or robots require clinical and wellness data to feed their machine-learning algorithms. Other businesses, known as data brokers, sell “scores” based on a person’s financial, physical, and mental health to life insurers, employers, and landlords.

Blocked from direct access to health records by the privacy rule, these data brokers have simply created their own facsimiles of patients’ health records by blending together HIPAA data (“laundered” through public health agencies), patient-curated data, and medically inflected data. They succeeded in creating health-related “big data” in a HIPAA-free zone.

Technology continues to broaden the scope of health care and wellness so an increasing percentage of health and wellness data use will not be subject to HIPAA with its custodians being unregulated or only thinly regulated.

What must seem to be a long laundry list of complaints and criticisms about HIPAA has to be tempered with the acknowledgment that the limited protection against the misuse of health information provided by the HIPAA rules is a positive outlier in U.S. data protection. Consumer data circulating in other domains lack any such substantive protection.

Unfortunately, HIPAA is so uniquely tied to the idiosyncratic structure of U.S. health care that it fails as an exemplar for other domains. And the HIPAA architecture makes it likely that it will continue to struggle to keep up with technologically mediated health care and the commercialization of health data.

The partial rebuttal to this criticism is that the U.S. Congress is obligated to and can provide strong protection for health data circulating outside of traditional health care entities. For example, the HITECH Act authorized the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s health breach notification rule that protects data in user-curated health records.

But Congress has yet to agree on broader consumer data protection akin to what the European Union and the state of California have adopted. As a result, patients continually bombarded by their health providers’ privacy notices may not realize that huge swaths of what they would view as their private health data circulate outside of HIPAA protection.

This essay is part of a six-part series, entitled Reflecting on 25 Years of HIPAA.