Scholar shows that regulatory bodies use arrests as informational proxies—but that this use has its costs.

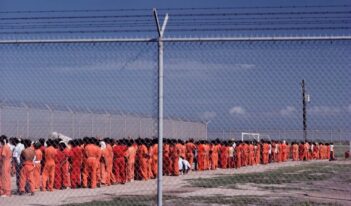

Approximately one in three U.S. adults will be arrested by the age of 23.

This striking statistic shows that the arrest process is a common experience for many Americans. An arrest is the first step into the criminal justice system and can ultimately lead to a conviction.

But arrests also have an adverse impact outside of the criminal justice context. Even if an arrest does not result in a conviction, actors outside the criminal justice system can still access and disseminate arrest information. Such dissemination results in profound regulatory consequences, argues Eisha Jain, a professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

An arrest itself is enough to trigger a regulatory decision from a noncriminal justice entity. Regulatory bodies use arrest information to monitor and track individuals. Jain examines how some officials use arrest information to inform enforcement actions—focusing on immigration officials, public housing authorities, licensing bodies, and child custody services.

For immigration purposes, enforcement officials use arrests as a screening tool. Local police and federal law enforcement share arrest information with each other. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement then uses this information as “a proxy for its own removal policies,” explains Jain. If the agency decides that an arrested noncitizen fits into a removal priority category, immigration officials can assume custody of the individual. Although examining arrest information is a convenient method for screening individuals, Jain warns that the link between criminality and unauthorized immigration is tenuous.

In the public housing context, officials rely on arrests to signal a tenant’s potential breach of contract. Because public housing has limited capacity, housing officials use arrest reports to monitor the premises and anticipate lease violations. Public housing tenants are at risk of eviction if any household member or guest engages in criminal activity—even if the tenant did not know, or did not have reason to know, about the activity. Jain highlights that eviction decisions based on a single arrest can affect the entire household, and it is difficult for tenants to contest unverified arrest reports in court.

Similar to public housing officials, employers and professional licensing bodies can use arrest information to monitor individuals. Law enforcement officials even notify some employers when arresting one of the latter’s employees. Although this notification does not contain the factual basis for the arrest, licensing authorities and employers have wide discretion on how to address the arrest. Jain suggests that, without proper oversight, this discretion can result in unpaid work suspensions for workers who are nonthreatening or who were wrongfully arrested.

In child protective and foster care services, an arrest notification can signal potential risk to a child. But unintended consequences may arise, says Jain. For child protection cases, an arrest that does not proceed in the criminal justice system may nonetheless cause local law enforcement to involve child protective services unnecessarily. In foster care situations, some states require background checks for adult and even juvenile household members. The arrest of a household member could jeopardize the entire family’s placement status. In both instances of social services, the use of arrests can severely disrupt families.

In many circumstances, regulatory entities interact with one another to use arrest information. On the one hand, agencies cooperate with each other to achieve their respective goals. For instance, immigration and criminal law officials share an interest in mitigating security risks, and prosecutors can wield potential eviction or deportation actions as leverage in plea negotiations.

On the other hand, the use of arrest information by regulatory officials may conflict with the aims of criminal justice. The circulation of such information to noncriminal justice actors can diminish the community’s trust in the police. When information about a person’s arrest does not include the full story of the incident, but officials still use such data to justify regulatory action, officials amplify this distrust. Examples include crime victims who face adverse outcomes due to reporting, and individuals that law enforcement officers unlawfully arrest.

One option to prevent the broad use of arrest information would be for regulatory officials to maintain administrative discretion in how they use such information. Although this individualized discretion is important, Jain argues it should not be the only solution. The use of administrative discretion lacks consistency, clarity, and timeliness. It also intensifies some inherent problems of the criminal justice system, such as the disparate impact on racial minorities who are more likely to be arrested, and an officer’s sometimes misguided decision to make an arrest.

Instead of increased discretion, Jain focuses on greater oversight and transparency in the use of arrest information. For example, she proposes restrictions on arrest sharing. Some policy options include automatic expungement of non-convictions and limits on sharing arrest records.

Jain also urges other actors, either from inside or outside the criminal law system, to address the use of arrests as regulatory tools. For example, criminal defense attorneys should advise clients on how arrests can lead to noncriminal social ramifications. Moreover, prosecutors could evaluate and dismiss improper arrests early on, and then inform other regulatory actors that the prosecutor will drop the charges. Jain also suggests that an independent third party should evaluate the reliability of the arrest information and identify unintended policy outcomes.

Because arrests are imperfect indicators of risk, Jain concludes that officials need to reevaluate how they use arrest information for regulatory decisions.