Former regulator argues that proposed SEC rules open up new regulation of securities markets.

The mission of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is to protect investors and to define what businesses need to tell the market. Public disclosure of company information forms the standard tool for accomplishing that mission, and the SEC has proposed broader disclosure in less familiar areas, such as climate impact.

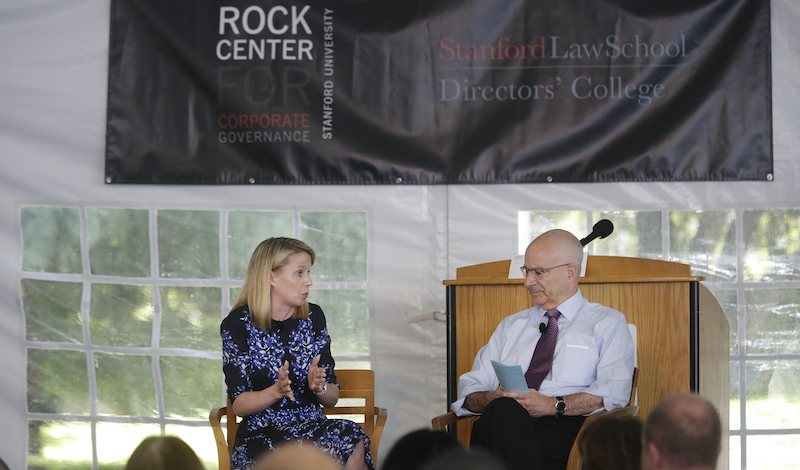

But the SEC might expand beyond traditional disclosure, according to a comment letter by Stanford Law School professor and former SEC commissioner Joseph Grundfest. Grundfest argues that the SEC’s proposed prohibitions on certain contract terms in investment advising go far beyond disclosure and impose substantive regulatory obligations. This development presents multiple problems for the SEC, he argues.

When investors look to pool money into an investment fund, they sign a contract with an investment advisor to manage the fund’s investments and assets. This contract, known as the investment advisory agreement, controls the relationship between the fund’s investors and the fund advisor, such as how the advisor plans to invest the fund’s assets and how the fund will compensate the advisor for its services.

The SEC’s proposed rules would prevent investors and advisors from entering into certain arrangements when creating a private investment fund—a subset of funds that exist outside of most current SEC regulation under the Investment Company Act of 1940. For example, the rules would ban certain fee arrangements, agreements to limit liability for advisor services, and loans from private fund clients.

Grundfest notes that the investors likely to be affected by this rule would be sophisticated investors who know what to expect when negotiating an investment advisory agreement, even though one of the goals of SEC regulation is to protect unsophisticated investors. So these investors—who put money into venture capital firms, private equity funds, and hedge funds—would receive greater protections than unsophisticated investors, which Grundfest argues would create “internal contradictions” between the levels of protections for different kinds of investors.

As an example of how the rules would set up such contradictions, Grundfest uses the prohibition of contract terms that allow indemnification for “a breach of fiduciary duty, willful misfeasance, bad faith, negligence, or recklessness.” Grundfest asserts that U.S. state and federal law allow indemnification and let sophisticated investors take greater risks than unsophisticated investors. Some foreign jurisdictions also allow waiver of certain protections for “sufficiently sophisticated investors,” so the SEC could create a glaring break with market rules already set up by state legislatures, the U.S. Congress, and foreign nations.

Grundfest also argues that the proposed rules only limit the options available to these investors instead of protecting them from harm, moving the SEC into the business of regulating the substance of investment. Grundfest worries that this expansion will transform the identity of the SEC into a “merit regulator,” which would represent a departure from the agency’s history and philosophy.

SEC Chair Gary Gensler affirmed that the SEC provides a “core bargain” to investors: investors can take their own risks as long as accurate and complete disclosure informs investment decisions. But Grundfest predicts that a shift to merit-based regulation of contract terms would completely destroy that paradigm by restricting the ability of investors to make their own decisions “with full disclosure and absent fraud.”

Grundfest points out that, if the SEC expands into this role, it would need to manage special interest pressure and choose between different substantive regulations, rather than simply require disclosure. The SEC could also easily descend a slippery slope and start expanding these prohibitions to all investors, Grundfest warns. He argues that the SEC must acknowledge this possible shift and give fair notice to the market if it adopts the proposed rules.

Beyond concerns about the proposed rules and the possible effects on the SEC’s role, Grundfest expresses doubt about the SEC’s stated rationale for the proposed rules. Grundfest contends that “the Commission provides no evidence of market failure” in the market for investment advice and fund management.

The SEC relied on approximately two dozen past enforcement actions from the past two decades to justify the proposed rules, but Grundfest argues that these actions do not provide a sufficient basis for a shift away from disclosure. According to Grundfest, the SEC’s reliance on these enforcement actions appears without context and does not show the significance of advisory agreement terms. By Grundfest’s count, the financial recovery from the cited enforcement actions totaled only 0.16 percent of the SEC’s recoveries across the same time period.

Grundfest recommends withdrawing the proposed rules for reconsideration. He concludes that any similar, future rule needs to address the concerns he raises before becoming final.