Scholar argues that FDA should be the sole regulator of cell-cultured meat.

When it comes to the regulation of lab-grown meat, there may be too many cooks in the kitchen. A battle between two federal agencies that both claimed sole authority to regulate cell-cultured meat ended in 2018 as a plan for these agencies to regulate these products jointly. But is this plan the right path forward for the regulation of cultivated meat?

In a recent article, Tammi S. Etheridge of Howard University School of Law argues that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is well equipped to regulate lab-grown or cell-cultured meat independently, and that the 2018 plan issued by FDA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for joint regulation is both unnecessary and inappropriate.

For example, as of November 16, 2022, FDA had Under joint regulation, the producer must now jump through the additional hurdle of seeking USDA approval.

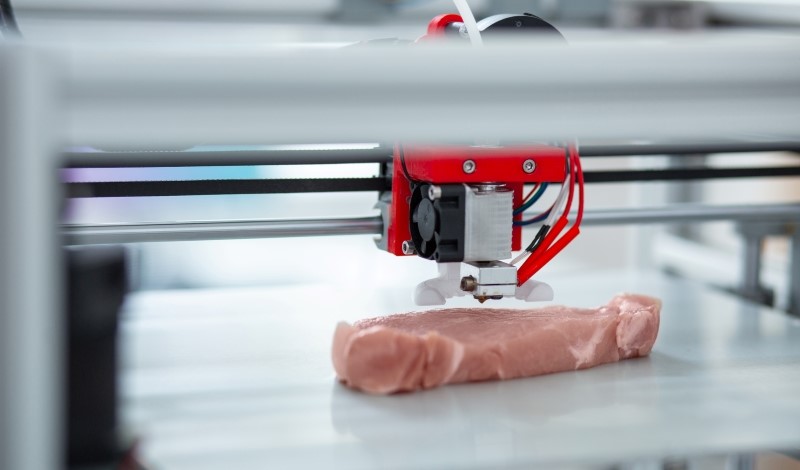

Etheridge first lays out the process of creating cell-cultured meat that FDA and USDA proposed in their joint plan. According to that plan’s first step, scientists would sample tissue from a live cow, extract stem cells from that sample, and place them into a culture of nutrients and hormones. Sampling would occur in an FDA-regulated laboratory, where stem cells could grow into fibers, eventually forming a muscle.

FDA would then oversee cell collection and growth, but would have to report whether harvested cells were suitable for processing into meat to USDA. USDA then would control production, the pre-approval process for meat labeling, and the content of the labels. USDA would also inspect the place where processing happens to ensure proper labeling and safe conditions.

Despite this planned regulatory framework, Etheridge argues that USDA is an inappropriate regulator for cell-cultured meat due to what she sees as its pro-industry bias, lack of applicable expertise, and lack of jurisdiction.

USDA is tasked with maximizing the agricultural industry’s profit and minimizing its losses, according to Etheridge. At the same time, the department also seeks to improve nutritional health. But Etheridge suggests that USDA has long prioritized supporting the agricultural industry over the public’s nutritional health. Etheridge goes one step further, stating that USDA acts as a lobbyist for the livestock lobby.

USDA has expanded the dairy market, for example, in opposition to science supporting that dairy consumption has negative health effects, according to Etheridge. She worries that the same industry support which expanded the dairy market could affect USDA’s regulation by biasing product labeling in favor of industry that could advocate stringent labeling rules that hinder market success for cell-cultured meat producers.

Etheridge asserts that the beef and cattle lobbies would advocate labels that significantly differentiate cell-cultured meat from ordinary meat to protect their share of the meat market. Meanwhile, a Consumer Reports survey found that consumers to show that cell-cultured meat is different than meat without removing the word “meat.” Etheridge explains that USDA would likely prioritize the industry’s input here rather than relying solely on science about cell-cultured meat. Following the industry’s preferences could result in biased labels which turn consumers away from purchasing cell-cultured meat, Etheridge warns.

USDA’s expertise is also largely irrelevant to cell-cultured meat processing, Etheridge argues. USDA ensures that livestock animals are healthy and fit to slaughter and that food is processed under sanitary conditions in meat packing facilities. USDA’s comparative expertise is not in monitoring labs, where cell-cultured meat is created.

Etheridge also cautions that USDA lacks authority to regulate cell-cultured meat. The federal statute USDA would presumably seek to use to regulate cell-cultured meat—the Federal Meat Inspection Act—defines meat food product as made from an animal’s carcass. But cell-cultured meat is derived from cells and falls outside of the statute’s scope, according to Etheridge. USDA considers meat to be muscle from the skeleton of livestock, which also excludes cell-cultured meat.

USDA’s partnership is thus unnecessary to regulate cell-cultured meat, Etheridge argues. She views FDA as a capable and appropriate sole regulator at each step of the process of overseeing the production of lab-grown meat.

Etheridge concedes that USDA will always have authority over cattle before they have their stem cells extracted by scientists. But FDA already inspects facilities that manufacture certain food and drug products and establishes sanitation and safety controls, indicating that it is capable of overseeing the safe manufacturing of cell-cultured meat.

Ultimately, Etheridge argues that FDA has preexisting regulatory processes for other processed foods and drugs that are much more similar to those required for cell-cultured meat than are USDA’s animal-based processes.

A notable difference between USDA inspection and FDA inspection is that USDA conducts real-time inspections by stationing an inspector constantly at a meat manufacturing facility, whereas FDA only conducts periodic inspections of food processing facilities. Etheridge acknowledges that some members of the public may view constant presence more favorably, but she counters that FDA has the authority to inspect a facility at any moment. Because of the constant potential for inspection, facilities currently under FDA regulation are very careful, Etheridge asserts. She does not view this difference as a compromise on safety or quality.

FDA should never have relinquished any oversight authority to USDA, Etheridge concludes. To solve the issue of joint regulation, Etheridge urges either USDA to return authority back to FDA or Congress to grant FDA sole authority over regulating any and all cellular agricultural products. She doing so could ensure that agencies regulating cellular meats allow society to reap the benefits of this new innovation and act in the interest of the people, not the industry.