Researchers explore the optimal cost-benefit considerations of medical device cybersecurity risks.

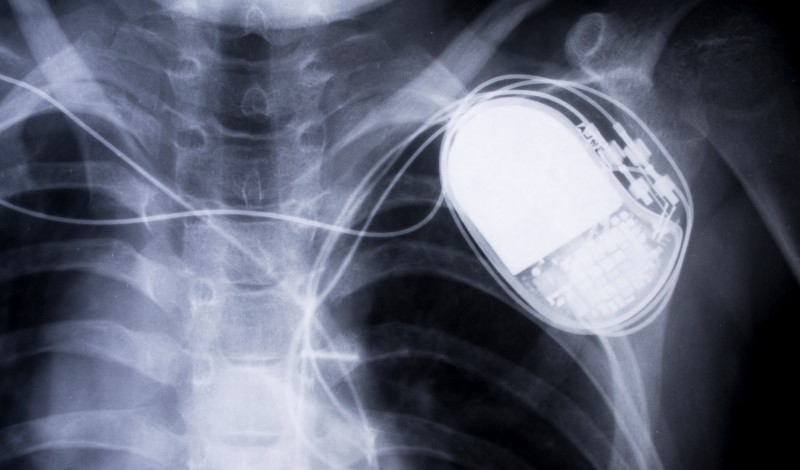

A jolt of electricity strikes the heart and neither love nor nature is behind it. Rather, a hacker has accessed a pacemaker with wireless capability and discharged a deadly surge. This worrisome scenario is but one of many possible risks from cyber-physical devices that are susceptible to cyberattack.

In a recent research paper, Christopher S. Yoo and Bethany Lee at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School urge the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop a new regulatory framework governing cybersecurity risks associated with medical devices.

Yoo and Lee argue that cyber-physical medical devices pose novel challenges to FDA’s traditional approach to evaluating device safety and effectiveness. Unlike other software, cyber-physical devices are embedded in an environment that is unpredictable and unbounded. And unlike traditional hardware devices, risks to patients may stem not just from a malfunction but also from intentional, malicious actors.

Given these factors, it is not possible to eradicate all possible cybersecurity risks for a given device. Instead, Yoo and Lee argue that device developers must establish an optimal level of cybersecurity that is not overly burdensome, costly, or a hindrance to device functionality. But exactly which risks must be mitigated, and which may be considered reasonably acceptable, may remain uncertain to medical device developers in the absence of clear agency guidance on the issue.

FDA has published a series of guidance documents over the last decade focusing on cybersecurity, most recently in 2018. These guidance documents acknowledge that residual risks are unavoidable and that certain acceptance criteria for risks must be established for medical devices to be deemed “trustworthy.”

FDA vaguely defines “trustworthy” medical devices, Yoo and Lee argue, as ones that “(1) are reasonably secure from cybersecurity intrusion and misuse; (2) provide a reasonable level of availability, reliability, and correct operation; (3) are reasonably suited to performing their intended functions; and (4) adhere to generally accepted security procedures.”

What is reasonable is largely up to the manufacturers to decipher when attempting to design safe but innovative products to bring forth for FDA review.

Yoo and Lee explore various methods of cost-benefit analyses that the agency could adopt to fill this regulatory gap. The first hurdle, however, will be convincing FDA that it has the authority to consider non-therapeutic factors, such as increased prices or development costs, at all.

The agency’s authorizing statute, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), tasks it with ensuring device safety and effectiveness by “weighing any probable benefit to health from the use of the device against any probable risk of injury or illness from such use.” Although the statute does not explicitly prohibit economic considerations, as a matter of policy, FDA bases its benefit-risk assessments solely on scientific determinants.

FDA disclaims the possibility of disapproving a device or therapy on the basis of its cost. Yoo and Lee argue, however, that judicial precedent, statutory interpretation, and the agency’s own policies do not preclude economic considerations, even if the agency has yet to act on them.

Judicial precedent in which the U.S. Supreme Court has struck down cost considerations, such as Whitman v. American Trucking Associations, produced carveouts to avoid compliance with rules or standards altogether. In the case of medical device cybersecurity, the cost-benefit analysis would supplement FDA’s “reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness” standard.

Statutory silence and ambiguity in the FDCA also lean toward permissibility, Yoo and Lee argue. They claim that because the FDCA does not overtly rule out consideration of cost, FDA’s decision to read “reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness” to include cost considerations should be granted judicial deference.

In fact, another agency has successfully interpreted silence in its authorizing statute to use a cost-benefit test: the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). The Federal Trade Commission Act explicitly tasks the FTC with “preventing and penalizing unfair and deceptive practices.” In deciding whether conduct is unfair or permissible because it is balanced by “benefits to consumers or competition,” the FTC does consider economic costs.

When translated to medical device cybersecurity, a test similar to that employed by the FTC would assess the costs and benefits of the decision to add or omit a particular cybersecurity safety feature to a given device. The benefits of reduced costs and improved functionality on one hand must outweigh the cost of the increased security risk on the other, according to Yoo and Lee. A cybersecurity feature that offers minimal improvement to safety but at excessive cost would not be necessary for the “reasonable assurance of safety,” they say.

Yoo and Lee explore other methodologies of cost-benefit analysis including the risk-utility calculus used in medical device product liability tort litigation and incremental cost effectiveness ratios common in health care economics contexts. Yoo and Lee recommend, however, that FDA establish a cost-benefit framework resembling the FTC’s unfair conduct evaluation, as it is easiest to administer and provides the most robust legal justification for FDA’s authority to consider economic costs in assessing medical devices.

No matter what path the agency takes, as long as 100 percent cybersecurity remains out of reach, the level of acceptable safety should be determined by some form of cost-benefit test, Yoo and Lee conclude.