Scholars propose avenues to improving the regulation of clean food labels.

“If you can’t pronounce it, don’t eat it.”

This adage, first articulated by author Michael Pollan in a 2008 interview, has since transformed into a prominent diet slogan touted by food bloggers and marketers alike.

Weight loss trends and fad diets abound in modern American popular culture, with the weight management industry boasting $3.8 billion in annual revenue. One such trend—“clean eating”—reflects the values promoted in Pollan’s infamous statement, as it entails the consumption of foods in their less processed and more natural states.

Clean eating has skyrocketed in popularity since the publication of Pollan’s work over a decade ago and now holds the title of the most common diet among U.S. consumers. Industry experts have identified “clean” labels as the most prominent marketing trend of the decade for prepared food manufacturers.

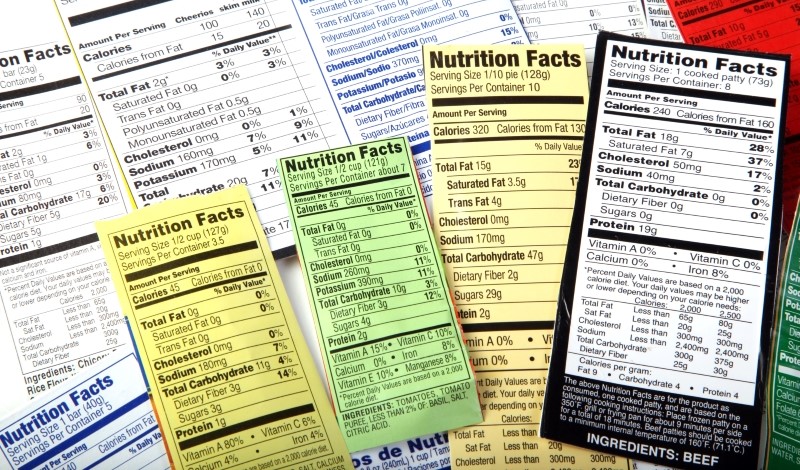

According to an article published in 2021 and written by Nicole Negowetti of Harvard Law School and several coauthors, the clean dietary labels adopted by such food companies can be easily misinterpreted by consumers, especially because manufacturers may apply these labels in an inconsistent manner, in reference to different qualities across different products.

With no shared, industry-wide definition of clean labels, such labels provide too much room for deceptive marketing. Negowetti and her coauthors argue that this “unregulated, undefined landscape” necessitates urgent action by state and federal policymakers to standardize or inhibit the use of clean labels and other associated terminology.

Although clean eating can, in moderation, deliver a nutritious diet focused on vegetables, fruits, beans, grains, and healthy fats, food companies have jumped to profit from the popularity of the trend, often to the detriment of consumers.

The Negowetti team contends that the use of clean labels requires regulatory intervention partly because such labeling may heighten the risk of disordered eating by contributing to the moralization of foods.

In addition, researchers found that clean recipes do not generally provide quantifiable health benefits, meaning that such labels may mislead consumers and distort their ability to make informed health-related decisions, explain Negowetti and her coauthors. For example, clean labels may promote misinformation about the curative effects of certain products, discouraging consumers with health conditions from pursuing empirically supported treatment options instead.

The Negowetti team evaluates various options for regulatory interventions to mitigate these public health concerns.

Under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) holds authority to regulate food labels. It can both require nutrition labeling and constrain the circumstances under which certain claims can be made about the nutrient content of a product.

Negowetti and her coauthors note that the regulation of clean labeling poses a specific challenge because such labels primarily reference what is not present within a product, which means that the labels likely qualify as protected instances of commercial speech that do not contain nutrient content claims.

Negowetti and her coauthors also find it unlikely that FDA would pursue a rulemaking to codify a formal legal definition of clean, partly because such a term is a “moving target,” meaning food manufacturers, if faced with a new rule, would merely pivot to other unregulated terms to achieve the same ends.

FDA could, however, respond to the use of clean labels in the same manner it has responded to the use of “natural” labels: namely, by providing industry guidance on the definition of the word, proposes the Negowetti team.

Such guidance, although not itself legally binding, would establish baseline instructions for preventing the deceptive or misleading use of clean labels. Negowetti and her coauthors suggest that this guidance require companies to disclose ingredients in a manner generally understood by consumers and to clarify why their product is labeled clean.

According to the Negowetti team, FDA should also publish public statements to debunk common myths and misconceptions about food labeled as clean, as this would create a more informed consumer base less likely to be deceived by misleading labels.

In addition, Negowetti and her coauthors recommend FDA diligently monitor the market to police deceptive labeling claims through proper enforcement actions, including the issuance of warning letters to secure voluntary compliance.

FDA’s enforcement actions to date have insufficiently managed the rapid propagation of clean labels, according to the Negowetti team. As such, FDA should exercise more active and responsive regulatory oversight mitigate the associated public health concerns.

Ultimately, the use of clean labeling, through its lack of uniformity in the marketplace, exemplifies the necessity of regulators’ role in moderating marketing claims to manage consumer expectations and protect consumer health interests.