The ongoing Google antitrust trial could shape the future role of big data in digital markets and artificial intelligence.

The ongoing United States v. Google antitrust trial in Washington D.C. raises complex and challenging questions about the role of big data in online markets. To the U.S. Department of Justice, big data amount to a significant and durable entry barrier in online markets. To Google, this characterization is overstated and misrepresents the role that data play in digital competition.

The evidence presented so far by the Justice Department in its antitrust case is worth looking at more closely. It is possible then to anticipate rebuttal arguments Google will likely make about its access to and use of big data. The task for U.S. District Judge Amit Mehta will ultimately be to decide where the weight of the evidence lies on the issue in his final opinion after the trial. Whatever the judge decides, debate over the role of big data in competition is likely to continue in connection with rapidly emerging artificial intelligence (AI) technologies.

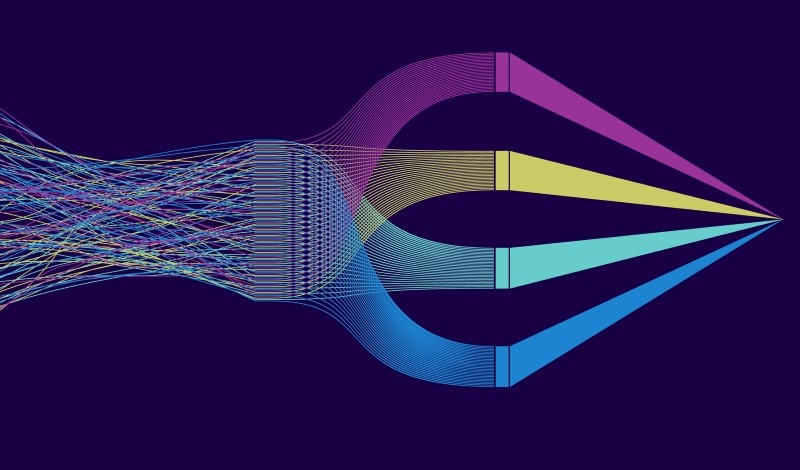

Although the term “big data” has only been part of the vernacular for little over a decade, it plays an increasingly consequential role in debates about digital markets. According to a 2016 Federal Trade Commission report, the term “refers to a confluence of factors, including the nearly ubiquitous collection of consumer data from a variety of sources, the plummeting cost of data storage, and powerful new capabilities to analyze data to draw connections and make inferences and predictions.” Big data play a particularly important role in digital advertising, which is the primary monetization model for many internet platforms.

A common rubric for thinking about big data relies on the “three Vs”: the volume, velocity, and variety of data, each of which is growing at a rapid rate as technological advances permit the analysis and use of this data in ways that were not possible previously. “Volume” refers to the vast quantity of data that can be gathered and analyzed effectively. The costs of collecting and storing data continue to drop dramatically. And the ability to access millions of data points increases the predictive power of consumer data analysis.

“Velocity” is the speed with which companies can accumulate, analyze, and use this new data. Technological improvements allow companies to harness the predictive power of data more quickly than ever before, sometimes instantaneously. And “variety” refers to the breadth of data that companies can analyze effectively. Advances across all of these three Vs, when combined, have ushered in the era of big data, the consequences of which we are grappling with across myriad public policy silos, including data privacy, security, and antitrust.

Although big data intersect with public policy in a number of ways, the role that data play in the antitrust context is under particular scrutiny in the ongoing Google trial. In its complaint, the Justice Department alleges that Google has monopolized the market for online general search and the related search advertising market.

It is no secret that Google has a persistently high market share in general search; its market share hovers around 90 percent and has done so for a decade or more. This high market share, however, is not in itself an antitrust violation. To prevail at trial, the Justice Department must also provide evidence that Google has taken action to maintain its monopoly through unlawful conduct.

The principal argument the Justice Department makes concerning Google’s conduct is that the company has unlawfully maintained its search monopoly through exclusive dealing arrangements with a host of companies, including Apple. Under a multi-billion-dollar contract, Google pays to be the default search engine on Apple iPhones and other devices. The Justice Department argues that these defaults are powerful and serve to foreclose competition from other search engines, including Microsoft’s Bing and DuckDuckGo.

Critically, Google’s defaults mean that substantially all search queries and data are exclusive to Google and give the company an unfair big data advantage over competitors. According to the Justice Department, this big data advantage creates a flywheel effect through which greater exposure to consumers leads to more data, which Google then uses to refine search results that attract more advertisers to use Google over its competitors. In turn, these revenues from advertisers enable Google to outbid for exclusive contracts, and so the flywheel continues to turn.

Big data come into play, according to the Justice Department’s argument, because of its role in the flywheel of building and reinforcing the scale needed to compete in the market for online search. The Justice Department’s complaint has noted that:

Scale is of critical importance to competition among general search engines for consumers and search advertisers. Google has long recognized that without adequate scale its rivals cannot compete. Greater scale improves the quality of a general search engine’s algorithms, expands the audience reach of a search advertising business, and generates greater revenue and profits.

The complaint also emphasizes that scale allows firms to generate enough revenue to recoup large upfront investments.

The CEOs of both Microsoft and DuckDuckGo recently provided testimony at the trial in support of the Justice Department’s case. They echoed the Justice Department’s arguments about how big data and the flywheel effect diminish their ability to compete with Google’s search engine.

Although Google has yet to present its rebuttal evidence, it is safe to assume that its defense with respect to scale and big data will rely on at least the following core arguments: that many types of data are readily available and replicable; that multiple entities, such as data brokers, can often collect and use the same set of data without foreclosure concerns; and that even big data can quickly become obsolete.

These arguments undermine the Justice Department’s notion that Google’s exclusive dealing gives the company a unique and unassailable competitive advantage. The arguments also beg the question, however, as to why Google pays billions to Apple to be the default search engine on iPhones if indeed there is no apparent advantage to Google in doing so. This and other questions will be front of mind for Judge Mehta as he weighs the evidence before him in the coming months.

How the judge in the Google case views data and the role they play in online markets will be important not only for Google, but also for future antitrust cases in digital markets. The precedent may also matter to how judges view nascent and future technologies that rely on big data to develop AI.

As the Microsoft CEO testified at the Google trial, AI depends on ever larger datasets to train on, making AI the next frontier for big data. As AI is integrated into search engines, this raises the question of whether Google’s existing big data advantage could serve to reinforce its existing monopoly. In his testimony at the Google trial, Microsoft’s CEO suggested that competing with Google’s data advantage will “become even harder in the AI age.”

Whatever precedent is set in the Google antitrust case could also prove instructive in how legislators in Congress think about big data’s role in digital markets. This is particularly timely as Congress is currently weighing legislation focused on the appropriate role of government in AI.

In the 1990s, Congress took a laissez-faire approach to the then-nascent internet and adopted a hands-off approach to legislation. Today, Congress has already adopted a different posture with respect to AI. Earlier this year, U.S. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) unveiled a legislative framework for AI, which mainly focuses on the privacy, national security, and copyright implications of the technology.

Although today the debate around the competition implications of big data may be central to the Google litigation, we might expect in the future to hear more such debate outside the courtroom as Congress considers big data’s role in competition over AI.