U.S. immigration office proposes a rule to address problems with the immigration court system.

Are immigration judges like Cinderella—that is, mistreated stepchildren who feel overworked and unsupported by their superiors within the U.S. Department of Justice?

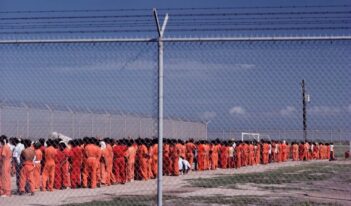

Some immigration judges think so. But they argue that a proverbial glass slipper cannot solve the challenges facing U.S. immigration courts, where 650 judges nationwide must navigate a current backlog of nearly 2 million cases.

The Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR)—a component of the Justice Department that adjudicates immigration cases—recently attempted to tackle the problem.

EOIR proposed a rule that would reinstate judicial control over case management that the Trump Administration eliminated. The rule would also seek to streamline the immigration appeals process.

According to immigration scholars, several factors contribute to the current backlog of cases in the nation’s immigration courts. These factors include increased interior and border enforcement, a surge in Central American migrants seeking refuge from gang violence, and a partial shutdown of immigration courts during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to these factors, some critics attribute part of the backlog to the Trump Administration. Less than a week before President Donald J. Trump left office, EOIR finalized a rule that critics claimed took docket control away from judges.

The rule sped up briefing schedules to the detriment of due process, and it impeded access to counsel for noncitizens with cases before immigration courts or before the Board of Immigration Appeals, an administrative agency that hears appeals from immigration court rulings.

The rule reduced judges’ discretion over their dockets to the extent that administrative closure was effectively eliminated. The practice of administrative closure allowed immigration judges to remove certain cases from their active docket temporarily, such as cases involving noncitizens awaiting visa decisions that may affect deportation proceedings.

The Trump Administration claimed that limiting judges’ discretion to pause cases would make immigration courts more efficient. Data scientists, however, have found that administrative closure reduces backlogs because judges can prioritize cases involving noncitizens who pose security risks or have been convicted of crimes.

Federal courts stopped the Trump-era rule a few months after it was finalized.

Through its recently proposed rule, the Biden Administration’s EOIR seeks to restore certain immigration court procedures that were in place before the Trump Administration. For example, the proposed rule would reinstitute and codify administrative closure.

The Biden Administration’s proposed rule would also reverse two Trump-era changes to the Board of Immigration Appeals’ briefing schedule, which dictates when parties to a case must submit certain legal documents. First, the Trump-era rule mandated simultaneous briefings, which required all noncitizens to submit their briefs at the same time as government attorneys.

Immigrants’ rights advocates argue that simultaneous briefings disadvantage noncitizens by requiring them to defend themselves before reviewing the government’s case.

The Biden Administration’s proposed rule would allow consecutive briefing schedules for non-detained immigrants—that is, individuals not in the custody of U.S. immigration authorities. Simultaneous briefing schedules would remain for detained immigrants.

Second, the Trump Administration’s rule reduced the maximum extension time for briefing schedules from 90 days to 14 days. Advocates contended that the 14-day limit on extensions hurt noncitizens who needed more time to find a lawyer.

In its new proposed rule, the Biden Administration’s EOIR stopped short of restoring the 90-day limit but proposed that the Board of Immigration Appeals should have discretion to manage extension requests on a case-by-case basis.

Stakeholders have mixed reactions to the proposed rule.

The American Immigration Council anticipates that, if finalized, this rule would help immigration judges preserve docket control and improve procedural safeguards for noncitizens.

Nevertheless, many immigration lawyers maintain that the proposed rule does not address the immigration court system’s structural flaws.

Retired immigration judge Dana Leigh Marks, for example, insists that protecting immigration courts from political interference requires removing them from a law enforcement agency. She urges the U.S. Congress to establish an independent court system under Article I of the U.S. Constitution, a position endorsed by the American Bar Association.

To help judges triage priority cases, some scholars recommend that EOIR create specialized dockets organized by subject matter, such as status adjustment or asylum.

Other scholars argue that assigning law clerks and support staff to immigration judges would improve accuracy in adjudication. Nicholas Bednar of the University of Minnesota Law School suggests that understaffed immigration judges, facing pressure to complete cases, are more likely to take “procedural shortcuts,” such as spending too little time reviewing cases, scheduling too many hearings per day, or shortening hearing lengths. These shortcuts, Bednar argues, violate noncitizens’ due process rights and lead judges to overlook evidence that may support granting deportation relief.

By contrast, when provided with one law clerk, an immigration judge was about 5 percent less likely to deport a noncitizen and over 4 percent more likely to grant asylum, Bednar found.

As drafted, the proposed rule may not deliver fairytale reforms to the immigration court system. But officials at EOIR hope that by empowering immigration judges to use discretion in docket management, the federal government can reduce case backlogs and lower the risk that efficiency comes at the expense of fairness.

EOIR will accept comments on the proposed rule until November 7, 2023.