Gigi Sohn explains how regulatory policy can promote net neutrality and narrow the digital divide.

In a recent discussion with The Regulatory Review, Gigi Sohn, former counselor to Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Chair Tom Wheeler, offers her thoughts on how regulation can improve consumer access to affordable and reliable internet.

Although access to affordable internet service has been a persistent problem since the internet transformed society in the early 2000s, the COVID-19 pandemic showed just how harmful lack of access can be. Employees were forced to work remotely and school children needed to attend class virtually while millions of Americans lacked the reliable internet service needed to make digital access possible.

In her discussion with us, Sohn describes how the “digital divide” and other barriers contribute to internet inaccessibility, especially for low-income and rural communities. She also offers solutions, including using regulation to expand consumer access.

Prior to serving as counselor to FCC Chair Wheeler, Sohn co-founded and served as president and CEO of Public Knowledge, a non-profit public interest group that promotes affordable access to communication tools and open internet while defending internet users’ rights. After her time at Public Knowledge, she served as special counsel for external affairs at the FCC.

Since working at the FCC, she has served as a fellow at Open Society Foundations and Mozilla Foundation, a distinguished fellow at Georgetown Law Institute for Technology Law & Policy, and a senior fellow and public advocate at Benton Institute for Broadband & Society. In October 2021, President Biden nominated Sohn to serve as an FCC commissioner.

A graduate of University of Pennsylvania’s law school, Sohn was the 2022–23 recipient of the Penn Carey Law Alumni Society’s Louis H. Pollak Award, presented each year to an alumnus of the law school who has advanced justice through service.

In addition to continuing to serve as a Benton Fellow, Sohn is currently the executive director at the American Association for Public Broadband (AAPB), a non-profit organization committed to supporting municipal broadband networks and helping build a public broadband network in the United States.

The Regulatory Review is pleased to share the following interview with Gigi Sohn.

The Regulatory Review: Why is it important for everyday consumers to have the ability to choose their broadband networks?

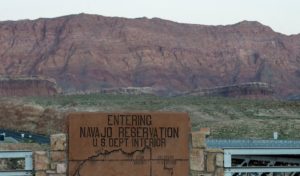

Sohn: First, let me emphasize why it’s important to be connected to broadband in the first place. Today, one cannot be a full participant in our society, our economy, our education system, our health care system, or our democracy, if he or she doesn’t have robust broadband internet access. Competition among broadband providers breeds choice, which means better, faster service at lower prices. But the broadband competition picture in the U.S. is not pretty. According to the FCC’s latest report, 58 percent of census blocks in this country have either one or zero broadband providers at the moderate speed of at least 100 megabits downstream and 20 megabits upstream, and 98 percent of the country has access to either zero or one provider at gigabit speeds. The situation is worse in rural areas and tribal lands.

TRR: Much of your work has centered around closing the digital divide by increasing access to broadband connectivity. How do you define the problem of the digital divide and why is it important?

Sohn: The digital divide is the result of multiple gaps, including connectivity, which tends to be a problem more in rural areas and tribal lands—although there are some urban communities that have connectivity so old and poor that it doesn’t meet the FCC’s outdated definition of broadband. The other gaps are affordability, access to devices, and digital literacy—that is, how to use a computer, how to use the internet, and how to overcome hesitation about both. You can’t solve a problem unless you understand it fully, and if policymakers and others believe that the sole answer to closing the digital divide is to build new networks, then this country will find itself with a divide that persists for many years to come. It’s not enough to have access to a network if you can’t afford it, don’t have a device to use it with, or don’t know how to use it.

TRR: The AAPB supports community-owned broadband networks. How can community-owned broadband networks help close the digital divide?

Sohn: Large, for-profit broadband network providers like Comcast and AT&T have one goal—to make the greatest return on their investment. And that’s fine—that’s capitalism. But it also means that certain households and communities either don’t get service or don’t get adequate service because providing service in those areas doesn’t maximize profits. That’s why many rural and tribal communities and some of the nation’s poorest neighborhoods have either no connectivity or inadequate connectivity at prices equal to or more than what wealthier neighborhoods pay for robust broadband. Community-owned networks have an entirely different goal—to ensure that every household in a community is connected with fast broadband at an affordable price. Some communities may be well-served by larger providers, but many others are not, and those communities should have the freedom to choose the network that best serves their residents’ needs.

TRR: The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) required that internet providers seeking a grant to connect underserved communities provide a letter of credit for 25 percent of the grant in order to qualify under the federal Broadband Equity Access and Deployment (BEAD) program. How, if at all, did this letter of credit requirement affect the federal government’s ability to close the digital divide? Why was the requirement changed?

Sohn: Let me expand a bit on your question. Not only did an applicant for a BEAD grant need to provide a letter of credit for 25 percent of the grant before it even applied for the grant, the applicant needed to provide matching funds of 25 percent of the project’s cost. Small, minority and female-owned and community broadband providers do not have that amount of capital to put up before they receive a dime to deploy new networks. To the extent that these smaller broadband providers are key to serving those parts of the country that larger providers are not interested in serving, modifying the letter of credit requirement was critical to closing the digital divide. In September, AAPB was one of 300 signatories to a letter asking NTIA and the U.S. Department of Commerce to allow for alternatives to the letter of credit requirement.

I’m delighted to report that on November 1, 2023, NTIA provided guidance that allows for alternatives to the 25 percent letter of credit requirement. These changes are directly attributable to the advocacy of AAPB and many other public interest organizations, broadband providers of all sizes, state broadband officials, and members of Congress.

TRR: The Biden Administration committed $42 billion to aid in closing the digital divide. How do you recommend the Administration allocate these funds to further its goal?

Sohn: Just to clarify—over the past two and a half years, Congress has committed over $75 billion to aid in closing the digital divide. $42.5 billion of that amount is for the BEAD program, which will pay for new high-speed networks to be built in unserved and underserved areas of the U.S. By law, the BEAD money is to be allocated to the states, and NTIA allocated the precise amounts to the states in June. So my recommendation at this juncture would be that the states allocate the money in a manner that ensures that broadband providers of all kinds—whether they be commercial, community-based, co-ops, large or small—receive funding. The process to allocate the money must not tip the scales in favor of the largest, richest providers.

TRR: Do you have any other recommendations for ways to expand broadband access throughout the United States?

Sohn: I have a lot of ideas, but I’ll discuss three. First, Congress must save the Affordable Connectivity Program, which is a $30 a month broadband subsidy for low-income households, or a $75 a month subsidy for tribal lands and “high cost” areas. Over 21 million U.S. households benefit from it, and it is due to run out of money in April 2024. In addition to aiding the poor, the Affordable Connectivity Program has become a significant source of revenue for large and small broadband providers and will help to make the BEAD dollars go much further. If Congress puts more money into the program for a year or two, that will give the FCC time to make the subsidy permanent as part of its Universal Service Fund, which, among other things, supports connectivity to libraries and K-12 schools as well as rural health facilities.

Second, Congress should pass a law preempting the 17 states that either prohibit or place onerous restrictions on community-owned broadband networks. Short of that, the states should repeal those laws—Colorado repealed its restrictions several months ago, for example. Limiting the growth of community networks ultimately harms a state’s economy, education, and health care systems, and drives businesses out while discouraging young residents from moving in.

Third, the FCC, NTIA, and the states should work to promote broadband competition. The FCC has taken some steps to limit exclusive deals between owners of multiple dwelling units such as apartments and condos, but it can and should do more. It can also require incumbent providers to make their networks available for resale by competitors. The White House, NTIA, and states should promote “open access” broadband systems that allow for multiple broadband providers to use common infrastructure and market their services to the public. In some cities in Utah and Idaho, for example, residents have a choice of 10 or more providers. In Ammon, Idaho, one of those providers offers a high-speed service for just $10 a month.

TRR: Net neutrality has been another focus of your work. Notably, you worked for the FCC under the Obama Administration when it successfully issued a rule that promoted net neutrality. What exactly is net neutrality? What is the current status of net neutrality regulation?

Sohn: Net neutrality is the principle that the entity that controls the broadband pipe to your home should not act as a gatekeeper and favor or disfavor certain content, applications, and services on the internet. Broadband providers can slow down or speed up certain traffic or subject certain content and services to a limitation on data, but not others. It should be the user, not the provider, who chooses winners and losers on the internet.

For net neutrality rules to be legal, the FCC must have the ability to exercise regulatory authority over broadband as a general matter. In 2015, when I was at the FCC, we reinstated that authority by classifying broadband as a “telecommunications service” subject to Title II of the Communications Act of 1934. This placed the net neutrality rules we adopted on the firmest legal footing, and allowed the FCC to protect broadband users from, for example, privacy and data protection violations, price gouging, and fraudulent billing. It also gave the FCC greater power to protect public safety and network security.

Currently, the FCC has no authority to regulate broadband or adopt net neutrality rules because the FCC, under the Trump Administration, repealed those requirements in December 2017. Last month, the FCC proposed a rule that would reinstate the 2015 net neutrality rules and the FCC’s authority under Title II.

TRR: What should the future of net neutrality regulation look like?

Sohn: The 2015 rules are over eight years old, which is light years in internet years; business practices and consumer uses of the internet have changed a lot during that time. As a general matter, then, I would be cautious about specifying exactly what future rules should look like before seeing the record in the new FCC proceeding. I wrote a paper for the Day One Project suggesting some changes that might be made to the 2015 rules, but even that was already three years ago. I think what is most important is for the FCC to hew to the core principles for telecommunications services embodied in Sections 201 and 202 the Communications Act of 1934: openness, non-discrimination, and just and reasonable prices, terms, and conditions.

I will go out on a limb and suggest two things that the FCC is proposing to do that it should not do. The first is that the FCC should not preempt state laws and regulations that provide even greater protection for consumers and competition than the rules the FCC ultimately adopts. For example, the FCC is proposing to reinstate the 2015 net neutrality rules, but California passed a net neutrality law in 2018 that is stronger than the 2015 rules.

The second thing the FCC should not do is forbear—or not apply—the section of the Communications Act that would apply the Universal Service Fund fee to broadband providers. The Communications Act permits the FCC to refrain from applying parts of the law that would not be in the public interest. Not applying the Universal Service Fund fee to broadband providers will make it far more difficult for the FCC to save the broadband subsidy in the Affordable Connectivity Program.

The Sunday Spotlight is a recurring feature of The Regulatory Review that periodically shares conversations with leaders and thinkers in the field of regulation and, in doing so, shines a light on important regulatory topics and ideas.