Scholar critiques the movement to have regulators adopt business management strategies.

At a campaign fundraiser, former presidential candidate Ron DeSantis pledged to “start slitting throats on day one” to purge federal bureaucrats out of the “deep state.”

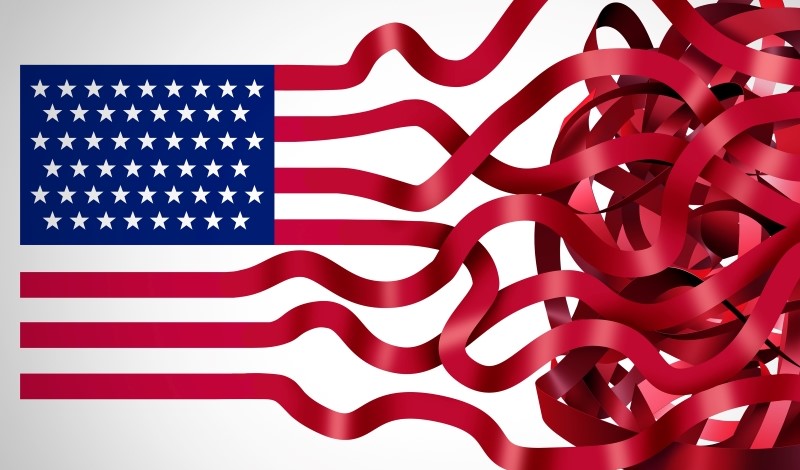

Some politicians and scholars argue that we can defeat the ineffective, biased regulators they describe by inserting business management techniques into regulatory practice—a concept known as regulatory managerialism.

One scholar, however, argues that regulatory managerialism fosters anti-administrative sentiments and perpetuates a form of “gaslighting.” In a recent article, law professor Jodi L. Short explains that business tools and techniques often lose their effectiveness when applied in the regulatory context. By ignoring this reality, Short contends that regulatory managerialism imitates classic gaslighting techniques by setting regulators up for failure and undermining their work.

Gaslighting “is an insidious form of manipulation and psychological control.” Victims of gaslighting are fed false information that leads them to second-guess themselves, their memories, and even recent events. Although this concept is normally associated with intimate relationships, Short claims that gaslighting tactics can target entire populations.

Regulatory managerialism mirrors common gaslighting techniques by delegitimizing regulators and reinforcing false narratives about “inept and overbearing” regulation, according to Short. She argues that regulatory managerialism deliberately sets up regulators for inevitable failure—a classic gaslighting tactic.

When they demand that regulators employ business strategies in their practice, advocates of regulatory managerialism fail to recognize the inherent differences between business and government, argues Short. Due to these differences, business strategies lose important functionalities when applied in the regulatory domain.

For instance, outsourcing is a common strategy used in business to lower labor costs, save time, and help workers concentrate on more important business activities. But Short contends that outsourcing government functions to private entities does not work effectively. She warns that, compared to private actors, the government faces heightened scrutiny over its actions, and any failure by third parties could have substantial reputational repercussions for the public agencies that retain them.

To mitigate this risk, regulators would need to monitor and assess the outsourced services, which then eliminates any potential efficiencies, contends Short. She argues that regulatory managerialism ignores these “substantial and potentially catastrophic costs” that make outsourcing untenable in the regulatory context.

Furthermore, Short explains that regulatory agencies face unique legal, political, and social constraints that restrain their ability to implement managerial strategies. For instance, business managers can define and target a specific customer segment they want to serve. This flexibility allows businesses to ignore hard-to-serve customers and to focus on addressing the specific needs of their most profitable customers, claims Short.

Regulators, however, operate under statutes, which govern who they must serve and the services they must provide. Regulators are often required to formulate policies for a large and diverse population and, therefore, business strategies centered on satisfying “customers” are inapplicable to them, Short argues.

In addition, businesses operate in an environment where failure is perceived as natural and even beneficial to innovation and entrepreneurship. Short explains that this environment affords firms and their workers the freedom to experiment and employ novel strategies.

In the regulatory context, failure is viewed very differently, contends Short. She claims that regulators and the public regard government failure as “shameful, to be avoided if at all possible, and potentially disqualifying of the entire government enterprise.”

Under these constraints, regulators are limited in how they can apply business tools—inhibiting their effectiveness and leading to inevitable failures, according to Short.

Short contends that these failures are then used to belittle and delegitimize regulators, employing another common gaslighting tactic. She explains that these attacks not only undermine regulators’ work as public servants but also distort their own sense of purpose, leaving them to question whether their efforts are merely contributing to a “hopeless cause.”

Short illustrates her argument by reference to the first campaign and presidency of former President Donald Trump, who openly criticized regulators and vowed to “remove bureaucrats who only know how to kill jobs.”

Many of his statements specifically targeted the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Following this anti-administrative rhetoric, over 1200 policy experts and scientists left EPA. This mass exodus had a ripple effect within EPA—severely delaying important regulations, harming enforcement activities, and negatively impacting staff morale, Short argues.

Short sees that the EPA case contains a warning about the harmful effects that gaslighting can have on public attitudes about government and on regulatory agencies’ staffing. She urges agency leaders to take proactive steps to mitigate these effects.

Short specifically suggests that agencies reaffirm their commitment to public goals over corporate interests. Regulatory leaders should highlight the important distinctions between government and business and reassert their duty to protect freedom, justice, and social well-being, states Short.

By redefining their roles and missions, regulatory agencies can renew their purpose among both the public and regulators themselves. Short argues that this will manage the public’s expectations and empower regulators.

Short also recommends that agencies do more to communicate their achievements to the public to combat negative narratives about regulation. She argues that gaslighting has deflected attention from significant regulatory successes. She suggests that agencies should engage in more routine and robust public communication about their achievements and enlist third parties, such as researchers or public interest groups, in disseminating positive information to the public.

By promoting their progress and achievements, regulators can transform how the public views regulators, contends Short. She sees such a transformation as important because agencies are needed to respond to complex issues such as climate change and emerging technologies. Regulatory managerialism, however, will only continue to hinder agencies’ effectiveness and reinforce tactics that gaslight the public, she concludes.