Scholar proposes a new regulatory model to strengthen workers’ bargaining powers.

Developing technologies may replace as many as 300 million full-time jobs. Workers increasingly fear that their job security is just one software update or algorithm away from becoming obsolete.

In a recent article, law professor Cynthia Estlund exposes yet another hidden cost to the rise of technology: workers’ depressed bargaining power. Estlund explains that improvements in automation have diminished U.S. workers’ ability to negotiate better working conditions and higher wages. She argues that states should intervene and use their regulatory power to address this issue. Estlund proposes crafting sector-specific regulations and involving workers in regulatory decision-making—a process she terms “sectoral co-regulation.”

Bargaining power is the ability employees have to negotiate and influence the terms and conditions of their employment. Estlund explains that this power has broad implications on workers’ health, safety, and financial well-being. Without this leverage, workers are more likely to experience lower wages and benefits, unfavorable employment terms, and greater workplace hazards and abuse.

In the United States, employees negotiate wages and working conditions through collective bargaining at their workplace. The federal government has also set national minimum standards on basic terms and conditions of work to protect workers that are unable to bargain collectively.

Workers wield considerable bargaining power when job alternatives are readily available and where their departure would impose significant costs on the employer.

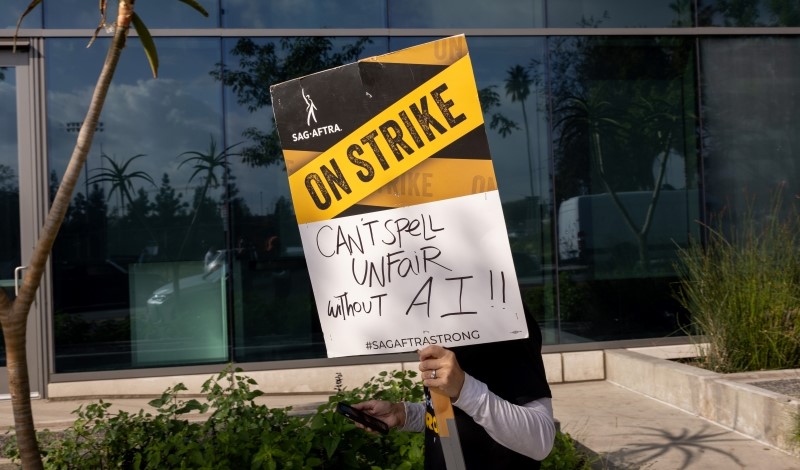

Estlund argues, however, that technological advancements have eroded workers’ leverage because employers can replace workers with technology.

Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and robotics can replicate a wide range of human capabilities that were once considered “uniquely human.” They can complete complex tasks quicker and more accurately than humans, improving firms’ performance and lowering costs.

For example, technology allows firms to contract out specific tasks and to phase out full-time positions. Estlund explains that technology has made searching for suppliers less costly, allowing them to take advantage of cheaper labor costs. Monitoring and communication technologies have also made these relationships more attainable.

Firms have also adopted “just-in-time” scheduling software—a tool that manages labor costs by scheduling employees based on fluctuating consumer demand. This new technology enables firms to replace full-time employees with part-time or temporary workers.

These developments in technology and their effect on workers’ bargaining power call for a restructuring of the how labor standards are bargained for and set in the United States, according to Estlund.

Estlund argues that the system will need to rely more on state regulatory power to raise labor standards. She proposes a new regulatory model—termed “sectoral co-regulation”—in which states would craft regulations based on particular industries with worker input.

To have workers engage in the regulatory process, states should draw on the strengths of collective bargaining and union representation, Estlund proposes. In this “co-regulatory” approach, workers would play an institutionalized role in setting or enforcing labor standards.

Estlund explains that workers’ integration in the regulatory system is essential because of their firsthand knowledge and interest in enforcing and improving workplace rights and labor standards. As a result of workers’ being part of the process, regulators can develop labor standards that are more responsive to workers’ specific needs, argues Estlund.

Estlund points out that a co-regulatory approach would not establish uniform labor standards but would rather set industry-specific standards, which would cover all workers in specific sectors of the economy. Estlund claims that this bargaining model would produce higher and more particularized standards that would not be feasible across all industries.

Some states have already enacted forms of sector-based regulation that involves worker input. For example, a recent California law, enacted by AB 1228, set a $20 minimum wage for fast-food workers and created the Fast Food Council—a regulatory body that can make recommendations for new standards specific to the fast-food sector. The council consists of nine voting members, including two representatives each for fast food employees and employee advocates.

California Governor Gavin Newsom said this law would give “hardworking fast-food workers a stronger voice and seat at the table.”

As technology advances and companies find new ways to leverage technology in their operations, workers’ bargaining power will continue to decline within the existing framework, Estlund argues. But by engaging workers in the regulatory process and setting standards for specific industries, regulators can help workers achieve better wages and working conditions, Estlund concludes.