Madeleine Bee, a senior chemical regulation and food safety consultant, discusses recent “forever chemical” legislation in California.

In a discussion with The Regulatory Review, a senior chemical regulation and food safety consultant Madeleine Bee offers her thoughts on recent changes to the regulation of chemical substances in California, emerging issues in food technology, and the evolving role of science in the lawmaking process.

In September 2023, the California legislature passed a bill that would have banned the use of polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in household and industrial cleaners. Although PFAS are used in cleaning products to aid in functions such as aerosolization, they have been attributed to adverse health effects and are known to remain present in the environment for long periods of time. The bill banning the use of PFAS was vetoed by the California Governor, but it would have extended to many products that Californians interact with daily such as hair care, automotive maintenance, and cleaning supplies. Due to California’s large population size relative to the U.S., a ban on PFAS was projected to impact national supply chains.

According to Bee, states should adopt new standards of chemical measurement to improve tests for the presence of dangerous chemicals. She supports California’s efforts to revise these standards and believes that higher bars for compliance will ensure safer products for consumers.

Bee received her doctorate in food science and technology from Cornell University in 2020 and is currently working as a senior scientist with the engineering consulting firm, Exponent. She is a member of the Institute of Food Technologies and the American Chemical Society.

The Regulatory Review is pleased to share the following interview with Madeleine Bee.

The Regulatory Review: In a recent article of yours on the regulation of polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), you discuss the bills passed by California’s legislature that target these chemicals. What are PFAS? How do they affect the environment?

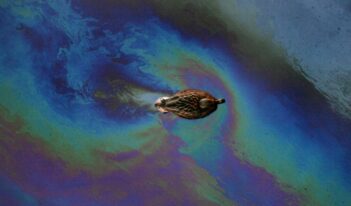

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a diverse class of over 14,000 chemicals primarily defined by the presence of carbon-fluorine bonds within a chemical structure. Manufacturers use these substances across industrial and commercial applications to enhance products such as paints, textiles, adhesives, sealers, foams, medical devices, lubricants, upholsteries, and carpets. PFAS are used in many of these products for their water-resistant, oil-resistant, and fire/heat-resistant properties. Because of these resilient characteristics, when certain PFAS are introduced into the environment, such as water or soil, they can remain for long periods of time. This is how PFAS earned the nickname “forever chemicals.”

TRR: What exactly would the California legislation on household and industrial cleaning products have done about PFAS?

California Assembly Bill 727 would have banned the intentional addition of PFAS in household and industrial cleaning products. The bill also would have set limits for the unintentional presence of PFAS that may come from contamination or other unknown sources. This language of the bill resembles previous PFAS-related bills that California has passed on cosmetics, menstrual products, children’s products, food packaging, and textiles. This means that manufacturers of these products would not have been able to use in their formulation PFAS-containing ingredients—specifically, any chemical with a single, fully-fluorinated carbon atom.

TRR: Do you see other states following California’s lead and trying to ban PFAS altogether?

California has historically led the way in many environmental regulations, but with PFAS there is a growing trend of state-level regulation. Some states, such as Washington, are following California’s product-focused approach. Other states, including Maine, have instituted reporting requirements for manufacturers and importers that use PFAS in their products, with bans going into effect later to give companies time to phase out these substances. I expect we will continue to see PFAS regulations at the state-level following these examples.

TRR: Outside of PFAS, what other regulatory issues do you believe should receive more attention nationally?

I personally find the regulation of alternative proteins and cell-cultivated meats to be an interesting area, given the novelty of these products and cross-agency collaboration required to bring them to market. The U.S. Department of Agriculture just approved the first cell-cultivated chicken product earlier this year through a joint regulatory framework with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), since both agencies have jurisdiction over these products. I am curious to follow any regulatory challenges that come up as other similar products are developed!

TRR: In your work, what challenges do you see lawyers or legislators confronting when trying to regulate issues with a large scientific component? Do you have suggestions for improving the way that science is treated or incorporated into regulatory policymaking?

To regulate emerging chemicals of concern, chemists need to be able to accurately measure the presence and quantity of those chemicals. How can you regulate something if you’re not sure it’s even there? This often presents a considerable challenge because of the novelty of these issues as standard analysis methods have not yet been developed, tested, and published by the appropriate agencies. This gap leaves lawyers, lawmakers, and regulators with data of varying quality. We are seeing small steps in the right direction with some recent regulations, such as the recent California PFAS bill discussed above. That bill included language around analytical validation and documented quality control procedures, which would have ensured that regulators had access to higher quality data that they could use to evaluate compliance.

TRR: You have an extensive background working with the chemistry of wine making. What kind of regulatory issues have you encountered when testing for odorants in wine? Does wine-making need more or better regulation?

Just as food additives are heavily regulated by FDA, there are many regulations pertaining to the labeling, contents, and additives for wines, which are issued at both the federal level by the Alcohol and Tobacco, Tax and Trade Bureau and by state-level boards. My first research project working with wine was measuring a quality indicator called volatile acidity, which is perceived as the smell of vinegar. Although this aroma is produced naturally by yeast during alcoholic fermentation and poses no threat to human health, it is still regulated in most wine-producing countries. The quality is generally considered a “fault” even at compliant concentrations, depending on the wine. Fortunately, there are few regulatory issues around wine aroma, just consumer preferences.

TRR: Our last question is a bit off-topic from regulation, but would you have any tips or recommendations for readers when it comes to selecting wines for their personal consumption?

The key to finding wine you enjoy is to be able to describe wines you have enjoyed previously. If you can remember a region, grape variety, or flavor that you tried and enjoyed, my advice is to go to your local specialty wine store and talk to the staff. They not only have more detailed wine knowledge, but they know the available products well. If you can give them some descriptors of what you liked previously and what you are looking for, they will be able to recommend similar wines or something new you might enjoy. To learn more about your preferences, try attending tastings at these shops or wineries where you do not have to commit to purchasing a whole bottle before you try.