Richard Lazarus discusses the implications of a shift in the Supreme Court’s attitude toward environmental regulations.

In a recent conversation with The Regulatory Review, Richard Lazarus, the Charles Stebbins Fairchild Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, reflects on the Supreme Court’s past and present attitude toward evaluating environmental regulations. Lazarus provides a path forward for agencies to address pollution and climate change in the wake of one of the most consequential Supreme Court terms for environmental protection.

Lazarus is a prominent scholar on environmental law, constitutional law, and the Supreme Court. He is the author of multiple books, including The Rule of Five: Making Climate History at the Supreme Court, which delves into the history of a monumental environmental law case, Massachusetts v. EPA, and the power of effective legal advocacy. His recent research has evaluated the Court’s environmental jurisprudence and how different Supreme Court justices approach environmental cases.

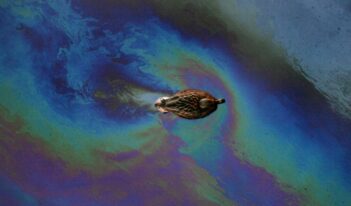

Lazarus graduated from Harvard Law School in 1979 and joined the school’s faculty in 2011. Previously, he served on the faculties of Indiana Maurer School of Law, Washington University in St. Louis School of Law, and Georgetown Law, where he founded the Supreme Court Institute. Lazarus has represented the United States, state and local governments, and environmental groups in the Supreme Court in 40 cases and presented oral arguments in 14 cases. He also served as the executive director for the President’s Commission investigating the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2011.

The Regulatory Review is pleased to share the following interview with Professor Richard Lazarus.

The Regulatory Review: As an environmental law scholar, you’ve written extensively about the Supreme Court’s environmental legacy. How has the current Roberts Court differed from earlier Courts concerning environmental regulation?

Today, the Roberts Court not only differs greatly from earlier Courts, but it bears little resemblance to the Roberts Court in October 2005, when the Chief Justice first joined the Court. Although the Court was then, like today, decidedly conservative, the controlling vote of Justice Kennedy was decidedly pragmatic, resulting in major wins for environmentalists in cases such as Massachusetts v. EPA and EPA v. EME Homer LLC and the avoidance of major losses in cases such as Rapanos v. United States. The current Court is far more conservative. And there is no reason to think any of those cases would be decided in the same manner by today’s Roberts Court. I have described these evolutionary trends at the Court more fully in a forthcoming article.

TRR: Last year, you argued that the Court’s decision in Sackett v. EPA served as a “judicial destruction” of the Clean Water Act. What did the Court decide in that case, and how does it reflect the Court’s current attitude toward environmental regulations?

The Court ruled in Sackett that the geographic scope of the Clean Water Act is limited only to those “waters” that are “relatively permanent, standing, or continuously flowing bodies of water ‘forming geographic features’ that are described in ordinary parlance as ‘streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes.’” As applied to wetlands, the Court further concluded that the Act applied only to those that are “indistinguishably part of a body of water that itself constitutes ‘waters’” as defined in the Clean Water Act.

The ruling dramatically reduces the decades-long understanding of the geographic scope of the Act. It undermines the statute’s ability to achieve its critically important purpose to protect the physical, biological, and chemical integrity of the nation’s waters. The ruling underscores the Court’s mechanical and reflexive willingness to rely on strict textual interpretation without regard to the essential context and purpose of one of the nation’s most important pollution control laws.

TRR: You recently characterized the Supreme Court’s decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo to overturn Chevron deference as a “convulsive shock to the legal system.” Can you explain why?

Those words were actually those of Solicitor General Prelogar in her unsuccessful effort to persuade the Court in Loper Bright not to overrule Chevron. For four decades, the Court’s Chevron ruling set forth the well-settled test governing the extent to which courts should—or should not—defer to federal agency interpretations of the statutes they administered. Legal conservatives, including Justice Scalia himself, originally championed Chevron, apparently so long as it legitimized the efforts of federal agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), to reduce the regulatory burden on industry.

But as legal conservatives, including those on the federal bench, increasingly learned that sauce for the goose was sauce for the gander, and Chevron deference could similarly promote judicial deference to tougher agency regulations, they had a quick change of heart. Suddenly, Chevron threatened the separation of powers, and a case that had been a stabilizing force for decades was jettisoned. And, just as the Solicitor General prophesized, industry law firms are already gearing up to challenge agency regulations across the federal government.

TRR: How do you see the Loper Bright decision fitting into the Roberts Court’s environmental legacy?

The ruling reflects, of course, a lack of respect for agency expertise. But more than that. Disturbingly, the reasoning underlying the Court’s repeated rulings against federal agencies leading up to Loper Bright suggests that a majority of justices embrace the extreme Trumpian view that agency career staff represent the deep state run amok and that the courts must accordingly rein them in. The Court’s nonjudicial attitude is little veiled in the harsh rhetoric used in questions the conservative Justices routinely pose to government counsel during oral argument. Completely gone is any notion that reviewing courts should presume the regularity and legitimacy of federal agency action. Indeed, the opposite presumption increasingly seems to be in play.

With that said, notwithstanding its clearly disruptive nature, the Loper Bright ruling includes its own seeds of limitation that may reduce its practical impact over time. The Chief Justice’s majority opinion relies on its construction of the Administrative Procedure Act, rather than strict separation of powers concerns based on the Constitution, and accordingly frees up a future Congress to expressly establish standards of judicial review akin to Chevron deference. In addition, while faulting the Chevron Court for assuming that statutory ambiguity, by itself, implicitly evidences congressional intent that courts defer to agency interpretation, the majority opinion acknowledges that “Congress has often enacted” statutes that expressly delegate to an agency “the authority to give meaning to a particular statutory term.” Even more significantly, the Loper Bright Court then affirmatively cites, in an accompanying footnote, illustrative provisions of the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act that already do just that. The federal environmental laws are riddled with similarly worded statutory provisions.

TRR: What other recent Court decisions have implications for environmental regulations? Are these decisions ones that concern you?

Not surprisingly, yes! The Court’s 2022 decision in West Virginia v. EPA, announcing the “major questions doctrine,” threatens the ability of EPA to address the compelling issue of climate change on a time scale necessary to avoid climate change’s worst consequences. The doctrine creates a test for upholding agency regulations that may, as a practical matter, be hard to meet given Congress’s inability to pass long-overdue national climate legislation.

The Court’s more recent ruling this past Term in Ohio v. EPA, moreover, threatens to upend the longstanding heightened deference courts have properly applied under the arbitrary and capricious standard to agency actions. And finally, the Court’s ruling in Corner Post on the last opinion day before summer recess invites a new wave of lawsuits challenging agency regulations that, because they were issued long ago, had been widely assumed to be time-barred from contemporary challenges.

TRR: Considering the recent Supreme Court decisions you have mentioned, what strategies do you recommend for environmental and natural resource agencies to address pollution and climate change moving forward?

First, those agencies will need to work for judicial deference. They can no longer merely assume it whenever they are interpreting ambiguous statutory language. A reasonable agency interpretation will no longer be sufficient to prevail. Agencies will need to persuade the court either that Congress affirmatively intended to delegate to the agency the discretionary authority to interpret the statute or, regardless of the evidence of such congressional intent, that their interpretation is the best. To accomplish the latter, agencies will need to rely heavily on the factors set forth by the Court 80 years ago in Skidmore v. Swift & Co. to determine what makes an agency’s statutory interpretation persuasive.

Second, the agencies will need to convince courts that a regulation does not trigger the major questions doctrine, requiring clear congressional authorization to validate the regulation. Finally, to the extent feasible, agencies will need to base their regulations on factual and technical assessments rather than legal interpretation.