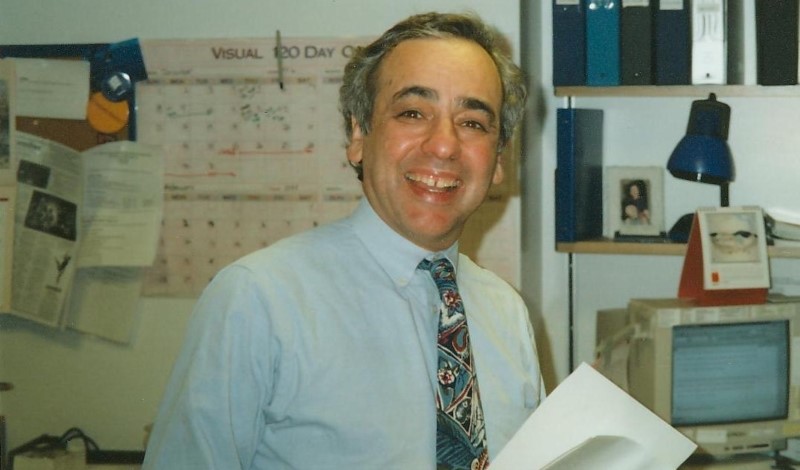

Howard Kunreuther will always be with us through his research and his inspiration.

When I arrived at what became Decision Research to work with Paul Slovic and Sarah Lichtenstein, Paul was already working with Howard Kunreuther on what would become the landmark study of flood and earthquake insurance purchasing behavior. For this reason, I can say that Howard was part of my professional life since I completed graduate school.

It took a while for me to appreciate fully what he and the disaster insurance project were doing. For someone like me, trained in cognitive experimental psychology and math, it was a brave new world: collaborating with economists; conducting population-based surveys; studying complex, ill-formed, real-world decisions, rather than stylized experimental ones that were designed to distinguish theoretical accounts; and trying to inform intricate public policies, like the National Flood Insurance Program.

There were conceptual precursors to the project. In founding decision science, Ward Edwards distinguished expected value, expected utility, and subjective expected utility decision models, based on whether people relied on their own judgment (utilities, subjective probabilities) or an external standard (monetary values, frequentistic probability estimates). Earlier experiments had compared these implications in tightly controlled settings. But Howard and his colleagues were asking homeowners about actual, fateful decisions.

I had a cameo role in the project, designing some stylized experiments and supporting our programmer, Bernie Corrigan, in creating an interactive computer game that simulated farm management, including insurance decisions. Thanks to the generosity of Howard, Paul, and others, I got close enough to the action to learn some lessons that have stuck with me through my career, and which were cornerstones of Howard’s lifework.

Disciplined empathy is at the heart of all decision-making research. We need to listen to people to understand and address their concerns. We need to care about them enough to place those concerns above our professional interests, such as testing or promoting favored theories.

Details matter, especially when asking questions about decisions that matter. We need to understand the technical details of decisions well enough to ask about the choices facing people. These details include disaster probability and severity, insurance coverage, and other specifics, such as insurance deductibles and premiums. We also need to be sure that people understand our questions and they understand our answers well enough to be talking about the same things.

Relationships matter when addressing complex decisions. We need teams with the expertise to pose meaningful questions about current decisions. We also need teams that can envision better options and work for the policy changes needed to make them happen. Like all teams, disaster research teams need the mutual understanding and trust that can only come through sustained interaction.

Teams need a common platform for coordinating their work. That platform must accommodate the contributions of all members and do so transparently enough for them to endorse its products. In deft hands, the subjective “expected utility” formulation of decision science can provide that platform, capturing the options, beliefs, and preferences of all parties.

Embracing these principles allowed the insurance project to identify essential economic and psychological differences between flood and earthquake insurance. Those differences had practical implications for how policies were marketed and regulated. They also had theoretical implications that Howard and his colleagues pursued both by conducting psychological experiments informed by economic considerations and by conducting economic analyses informed by psychological considerations. The current insurability crisis shows how sadly prescient the research was, and how pertinent its methods still are.

Over time, Howard and his colleagues took their hybrid research approach to other domains, including vaccines, climate change, energy conservation, and industrial safety. In each case, the work was good for society—by applying what we knew—and good for science—by identifying what we still needed to learn. In each case, success depended on the intellect and interpersonal skills needed create and sustain effective teams. No one had these skills like Howard did.

When we are lucky, the relationships from successful work teams spill over into our personal lives, so that future work also provides an excuse to get together. Howard was always there, in this way as well. We would meet at Gil White’s Boulder conferences, Society for Risk Analysis meetings, the working groups that Howard created, the Wharton workshops that he convened, and the stray trips that brought us in proximity.

Howard and his family also supported my family. During a year that we spent in Cambridge, England, Howard found an excuse for us to visit IIASA, where he was working to keep East and West from drifting further apart. My children, Maya and Ilya, still remember paddle-boating on the lake. Howard’s first wife, Sylvia, visited us in Cambridge. To this day, we keep crayon stubs and stickers in a wooden box within which she brought us a Sacher Torte. We also have fond memories of meals with his wife of 33 years, Gail, including some when we were lucky enough to be joined by Laura, Joel, and their families.

And Howard is still always there, for those of fortunate enough to have internalized the echo of his voice and energy, posing challenges and inspiring people to join him in meeting them. I can hear and feel that voice and energy, when I reflect on the trajectory of my own work, and in the lives that we have shared.

This essay is part of a series celebrating the life and scholarship of Howard Kunreuther, titled “Commemorating Howard Kunreuther.”