The Loper Bright decision leaves hundreds of pivotal health care regulations subject to litigation.

This past June, the U.S. Supreme Court shifted the ground under regulators by repealing Chevron deference to agencies in Loper Bright v. Raimondo and tasking courts with determining the “best reading” of statutes. Health care—one of the most technically regulated industries—will undoubtedly feel the impact, but how exactly?

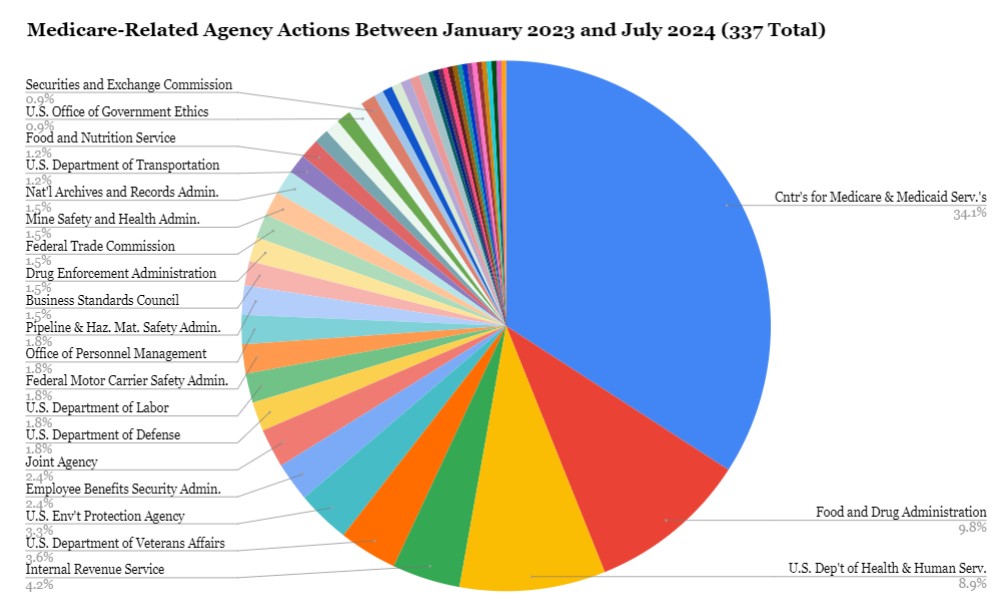

To understand better, we drilled down into 18 months of regulatory activity. By searching “Medicare” on Regulations.gov for the period between January 2023 and June 2024, we uncovered 341 individual agency actions—nearly one-third of which were final rules. When we broadened the search to “health,” we found 26,152 agency actions, 2,000 of which were final rules. Looking deeper at these rules reveals how the health care administrative state is now vulnerable.

First, health care regulation demands coordination and technical expertise. Although much health care commentary has focused on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, our “Medicare” search revealed more than 20 agencies and offices whose regulations relate to Medicare. As the chart below shows, some agencies are outside the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), such as the Department of Education, Department of Labor, Federal Aviation Administration, and Securities Exchange Commission. Eight regulations are coordinated by multiple agencies. This complexity will make it hard for the agencies to figure out how to Loper Bright-proof their work to the extent it might be feasible to do so.

Second, health care regulation often implicates multiple statutes and executive orders, which can further complicate deciphering a best interpretation. For example, in one proposed Medicare health technology rule last year, HHS cited at least three statutes and more than five Executive Orders. Rulemaking that builds on immense complexity requires facility with the statutory and administrative context that agencies know best.

Finally, our review shows three ways that health care regulation routinely addresses challenges that led to Chevron deference in the first place. Certain high-profile health care regulations were inevitably going to be reviewed by courts, such as those interpreting the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) antidiscrimination provision. But following Loper Bright, courts will second guess the routine work of agencies—defining statutory terms, interpreting unclear statutory language, and regulating in a quickly evolving field.

As in other fields, health regulations interpret terms undefined by Congress. Under Chevron, undefined terms were understood as a gap that Congress left for the agencies. In health care, those words often have technical context. For example, the ACA created “short-term, limited duration” health insurance” (STLDI) as a temporary form of coverage, exempted from the law’s consumer protections. But Congress did not define STLDI, and agencies interpreted it in the context of the ACA as a whole. In 2016, an Obama Administration regulation interpreted STLDI as a maximum period of three months. In 2018, the Trump Administration redefined it as an initial coverage term of up to 364 days that could be extended to cover 36 months in total. In 2024, the Biden Administration reinterpreted it as three months, with no longer than four months including renewals, reasoning that the duration was “faithful to Congress’s intent” and needed to “address the changes in the legal landscape and market conditions from 2018 to 2024.”

Some see Loper Bright as beneficially putting an end to such vacillation, but there are costs as well. The idea that there is a singular best meaning is naïve, and the assertion in Loper Bright that a static interpretation is preferred thwarts learning and refinement, or correction of regulatory missteps.

Regulations commonly address instances when Congress’s intended meaning is unclear—intentionally or not. Consider one Medicare statute provision with billions of dollars on the line: the formula used to calculate extra payments to hospitals that treat a large share of low-income patients, called disproportionate share hospitals. The statutory language is convoluted, and regulations interpreting it are routinely litigated. When the Supreme Court considered Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ interpretation of one aspect of the formula in Becerra v. Empire Health Foundation in 2021, the Justices poked fun at its indecipherability in oral argument, and Justice Breyer quipped that he was “baffled.”

The Court ultimately upheld HHS’s interpretation without relying on Chevron, but the arguments in this case draw attention to the absurdity of leaving to courts the tasks of interpreting technical, unclear, and contextual statutory language. Ambiguities remain regarding the disproportionate share formula. Our search uncovered additional final rules interpreting parts of the formula in 2023, and another phrase of the disproportionate share formula will return to the Supreme Court for examination this year in Advocate Christ Medical Center v. Becerra. These are the kinds of cases in which, if agencies are interpreting reasonably, courts should yield.

Perhaps the most vulnerable health regulations interpret statutes that have become unclear over time with industry advances—a common phenomenon in health care. For example, in April 2024, FDA issued a final rule involving the regulation of laboratory-developed tests, which are in vitro diagnostic products (IVDs) designed, manufactured, and used within a single clinical laboratory for purposes such as predicting cancer risk and aiding in diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease. More specifically, FDA deemed IVDs manufactured by laboratories devices under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, regulating them for safety and efficacy similarly to other IVDs under FDA’s jurisdiction. The widespread use and complexity of IVDs, let alone laboratory manufactured IVDs, was unanticipated when the Medical Device Amendments of 1976 were enacted, making it impossible to know whether Congress intended that they be regulated as devices.

In Loper Bright, the Court encourages Congress to legislate with greater clarity. Yet, the complexity and evolution of health care make it especially difficult to do so, even assuming the political landscape might allow consensus.

Although we can only speculate about the exact effects of Loper Bright, agencies’ work to promote health will be harder than ever. Health regulation is vast, technically complicated, and requires coordination and technical expertise. Matters of health are politically, morally, and economically contentious. Four of the top ten largest U.S. corporations operate in health care. They will be motivated to challenge regulations, and they will have plenty of opportunities for challenge, considering the volume and complexity of regulations over the course of the average year.