The Congressional Review Act offers a divided Republican caucus the opportunity to gut regulations.

The U.S. Congress is back and the U.S. House of Representatives is already roiling, as exemplified by the lobbyists and pundits who trail members and staff through the halls and into their offices. Republicans are already desperate to regain momentum after tripping out of the starting gate, even astride their newly minted control of both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue—a “trifecta” in Washington lexicon.

The first order of business was to elect a speaker. Despite an endorsement from President Donald J. Trump, Representative Mike Johnson (R-La.) squeaked through with just the right number of votes after failing on the first roll call, hustling off the floor, and dropping presidential phone calls on the most malleable dissenters. After the departures of Matt Gaetz, a former Florida Representative, Representative Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.), and Representative Michael Waltz (R-Fla.), the Republicans will hold the majority by two members. Johnson cannot afford to lose a single Republican unless Democrats are willing to help. He has already received a letter from eleven far right leaders of the House Freedom Caucus demanding that he deliver President Trump’s agenda without pandering to Democrats.

President Trump, for his part, has demanded that Johnson move “one big, beautiful bill” through the reconciliation process, which allows passage by simple majority in the Senate and would sidestep the 60-vote filibuster rule. President Trump’s proposed bill includes the extension and expansion of tax cuts for corporations and the super wealthy, new energy commitments to prioritize fossil fuels, and tougher immigration and deportation policies. President Trump also wants Congress to deal quickly with the debt ceiling.

Many backroom negotiations are inevitable, and the idea that a massive legislative package will be easier to pass could run into the reality that members will want innumerable concessions to take tough votes. The process will bog down, and Republicans must find something else to do.

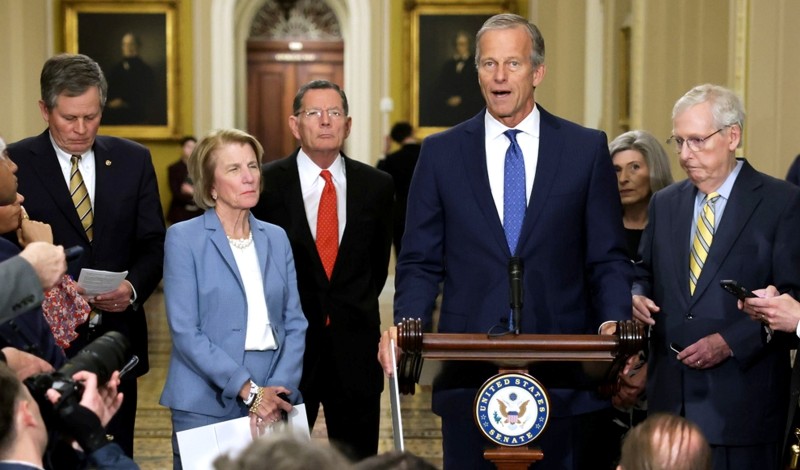

Senator Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has already fingered the most promising possibility—killing Biden Administration rules under the Congressional Review Act (CRA). The CRA allows narrow majorities in Congress to pass “resolutions of disapproval” for recently issued final rules.

Like reconciliation, it sidesteps the filibuster. Senate debate is limited to no more than 10 hours, which are evenly divided between a resolution’s supporters and opponents. Once a rule has been successfully repealed, the issuing agency cannot replace it with a new rule that is “in substantially the same form.” What this “salt the earth” provision means in practice is the subject of considerable debate, but it has frightened agencies from addressing crucial topics.

The CRA is a potent vehicle for creating the illusion of legislative productivity in an otherwise dysfunctional Congress. The last time Republicans had a trifecta, Congress repealed 14 rules by mid-May 2016. Rule repeals accounted for almost half of the legislation sent to President Trump’s desk during the first 100 days of his first term. To further grease the skids, the CRA defuses other procedural trip wires, including committee-of-jurisdiction markups, floor vote calendars, and conference committees.

But the real gimmick of the CRA, as these situations reveal, is its so-called “lookback provisions.” These provisions allow a new Congress to reach back and repeal rules issued late during the previous administration. That is because the CRA is supposed to provide both chambers exactly 60 legislative days to review a rule—a period that in practice translates to several months’ worth of calendar days. Under this accounting, the most recent lookback period began sometime in mid-August of last year. For those rules released late enough that the 118th Congress did not have 60 days, the lookback provisions transport them into the 119th resetting the 60-day review clock.

Critically, the lookback provisions also serve to bypass the CRA’s major Achilles’ heel—the U.S. Constitution’s Presentment Clause. CRA resolutions, like all legislation, require a presidential signature to take effect. But no president in their right mind would sign a law repealing one of her own rules. So as soon as a trifecta is achieved and control shifts to the other party, the previous administration’s regulatory accomplishments can be repealed with minimal muss and fuss. That was just the situation in which President Trump and company found themselves in January 2017, and just the situation in which they find themselves now.

As this piece goes to press in late January, a list of resolutions is becoming available. Most of these resolutions deal with regulatory actions focused on immigration or environmental protection. If the experience of President Trump’s first term is any guide, these modest initial numbers will multiply quickly and could easily expand to several dozen entries. How resolutions rise to the top of the heap and are approved by votes of both bodies, is rarely revealed but undoubtedly involves some mixture of the strength of the lobby supporting them, White House preferences, and the clout of the member listed as primary sponsor.

Early memos from high-profile law firms promote several controversial candidates. If Democrats remain united and even one or two Republicans in purple districts peel off, this effort may prove far less successful. But if President Trump works with congressional Republicans and the narrow House majority holds, we could see major damage to the rules that the Biden Administration issued late in the term.

For example, one of the startling developments of the 2024 campaign was the International Brotherhood of Teamsters’ decision not to endorse either candidate, although several locals broke from the union’s national leadership and supported Vice President Kamala Harris. This development prompted some pundits to predict “a dramatic change” in labor policy under a new Trump Administration. With due respect, we think this shift is highly unlikely.

Congressional Republicans have a few choices if they are looking to veto rules that help working people. For example, a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services rule subject to the CRA would raise the salaries of Head Start teachers and improve their working conditions. Its repeal could be the first step in eliminating the program, as suggested by the far-right’s Project 2025. Head Start extends access to pre-school for more than 500,000 low-income children, promoting “school readiness” through health, educational, nutritional, and social services. Created in 1965 under President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, it has ensured the future success of millions of children. The program empowers women economically because it allows them to pursue educational or career goals as they raise children.

The U.S. Department of Labor finalized a second rule in mid-December. It blocks efforts by coal mine owners and operators to shift their responsibility for paying benefits to miners suffering from black lung disease back to the federal government through the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, which is supported by an excise tax on coal tonnage and is billions of dollars in debt. Black lung disease is avoidable if coal owners suppress coal dust and silica within the mine. Many industry members attempt to evade regulations to prevent black lung, and since 1968 76,000 coal miners have died.

Turning to another favorite target, the CRA could be used against several rules the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued this past fall that the oil and gas industries and red state local governments will try to push onto the chopping block.

Methane is released into the air from a variety of sources, including facilities that produce oil and natural gas. As a greenhouse gas, it is 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide and causes about one-third of the climate change produced by human emissions. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 required a rule to curb methane emissions by imposing fees on inefficient onshore and offshore oil and natural gas producers. Most Americans sense that something is very wrong with the climate as drought, floods, and wildfires multiply. If rules such as this one are swept from the books and emissions continue, such conditions will become much worse.

Last but not least is a rule that requires the replacement of lead drinking water pipes. Based on extensive scientific research, the Center for Disease Control advises that no level of lead exposure is safe. Exposures at very low levels can cause neurodevelopmental problems in children under six and cause or exacerbate heart disease in adults. The nation has made progress in reducing lead in drinking water delivery systems but still has a long way to go. But because such systems are typically owned by local governments and distrust of science is rampant, resistance to the rule has spread.

Many Americans distrust government until they need it. Ironically, and fortunately, our expectations that government will respond to a crisis—fatal illnesses caused by working conditions, bad educational opportunities for children, the threats posed by climate change, or dangerous pollution—are sky high. Such responses cost money, take time, and need law to back them up. The CRA is a legislative “smash and grab”—designed to wipe the law off the books so easily that political backlash is almost impossible.

CRA resolutions have been rejected in the past. In 2017, Senator John McCain famously cast the deciding vote to block a resolution that would have repealed a U.S. Department of Interior rule meant to limit methane emissions from oil and gas development on public lands. Similarly, victories are within reach in the House, where the GOP majority is razor thin and party unity is fragile. The CRA should be repealed, but in the meantime specific rules can be saved.