Expert examines the regulatory challenges of robotic policing.

The year is 2086. An artificial intelligence program monitors the feeds from security cameras placed around the city. Swarms of police drones fly through the air conducting surveillance on suspicious individuals. Autonomous police vehicles patrol the neighborhoods, and, when necessary, disable and detain dangerous suspects.

This scene may seem like a page taken straight from the screenplay of a Hollywood blockbuster like RoboCop or Blade Runner—more science fiction than a realistic depiction of the future. However, Elizabeth Joh, Professor of Law at University of California, Davis, School of Law, argues in a recent paper that a future where the police use artificially intelligent machines capable of using force against humans is not only possible, but also probable. And the potentially far-reaching ramifications of police robotics, Joh states, raise “questions about what sort of limits and regulations should be imposed on robotic policing.”

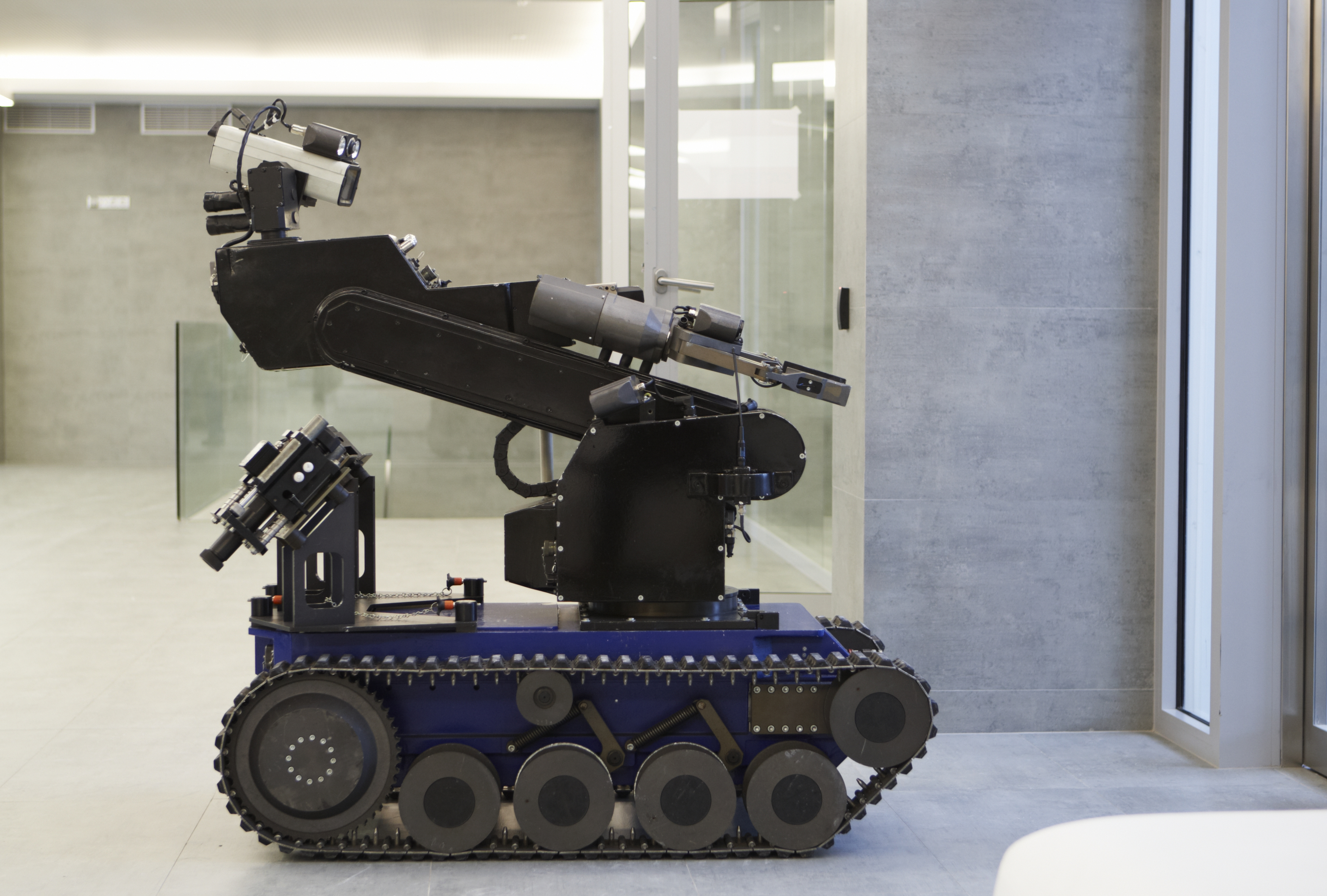

Police use of robots came to the forefront of regulatory and policy debates in the United States shortly after the tragic Dallas shooting in July 2016. The standoff between the police and one of the suspects of the shooting spree ended after the police reportedly used a bomb disposal robot to deliver and detonate explosives where the gunman took shelter. This move, which The Washington Post called “potentially unprecedented,” sparked a national debate about police use of remote-controlled devices and the legality of their deployment as a delivery mechanism for lethal force.

For instance, Seth Stoughton, Assistant Professor of Law at the University of South Carolina School of Law, reportedly said that, although the Dallas Police Department’s decision might raise some new issues, it was not particularly novel from a legal perspective. “The circumstances that justify lethal force justify lethal force in essentially every form,” he reportedly stated. “Once lethal force is justified and appropriate, the method of delivery—I doubt it’s legally relevant.”

Joh, on the other hand, contends that robots represent the “next leap” in how police perform their jobs, especially when considering the possibility of wholly autonomous robotic policing. She argues that this change will accordingly come with important regulatory questions: How much should police delegate decisions about the use of force to robots? How heavily should robots be armed? Under what circumstances should a robot be able to use force?

One question that Joh elaborates upon is that of the proper circumstances for the use of force. She explains that, normally, police officers may legally resort to the use of force, even deadly force, when a suspect “poses a threat of serious physical harm, either to officers or to others.” For these types of questions, courts typically look at the specific facts of each situation to see whether the use of force was a reasonable choice from the perspective of an average police officer on the scene. However, Joh emphasizes that in these decisions, courts “tak[e] into account the fallible nature of human judgment in volatile situations with high degrees of stress and emotion.” She notes that, in the context of robotic policing, what would be “reasonable” for a robot in any given situation is ambiguous because autonomous machines do not feel the stress or emotion that might otherwise muddy a human officer’s decision-making process.

Additionally, the permissibility of using force “assumes the perspective of officers who fear for their lives or safety,” Joh states. The use of remote-controlled or autonomous robots blurs this assumption because a threat against a robot does not necessarily constitute a threat to safety. Observing that the law traditionally values life over property, Joh acknowledges that if people treat robots as property, then police robots should not be allowed to defend themselves against human attack, even if the attacker intends to do the robot harm.

However, Joh contends that in the future, robots may occupy a category “that is neither purely property nor human,” giving them further leeway to defend themselves. To support this proposition, she looks, first, to research suggesting that humans tend to treat robots as neither dead nor alive, and, second, to an already-existing debate over whether the government should criminalize cruelty to robots in the same way that it criminalizes cruelty to animals. These discussions suggest that robots may deserve legal protections that extend beyond that of simple property, which would further inform and complicate the regulation of the use of force by robots.

These kinds of questions may seem abstract, but Joh asserts that the federal government is already grappling with many of them in a military context. According to Joh, the military has used robots for nearly a decade in the form of drones in the air and remote-controlled robots on the ground, and is planning for a future where nearly autonomous robots play a central role in warfare.

“What develops first in the military often finds its way to domestic policing,” Joh says. She explains that tactics and technology have trickled down from the military to the police in the form of training and surplus military equipment, and it would not be outside the realm of possibility to expect the same for effective robot technologies initially developed for military purposes.

She further argues that “[e]ven if this use of robots is still just a concept, we can anticipate the kinds of legal and policy challenges that might arise.”

Joh’s paper is published in the UCLA Law Review.