Scholar explores a new legal basis for regulating street and cyber-harassment.

For many women, a simple walk down the street to the grocery store can put them at risk of sexual harassment: kissing noises, whistling, or verbal taunts hurled in their direction by bystanders or passers-by.

Street harassment—or catcalling—occurs when an individual, most often a man, publicly comments through demeaning looks, words, or gestures on the physical appearance and presence of women they do not know in a public space. Along similar lines, cyber-harassment occurs when an Internet user sends demeaning or threatening messages to cause the recipient emotional distress.

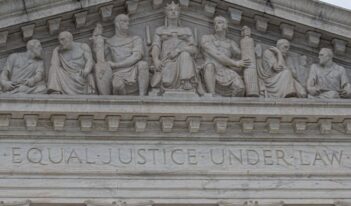

Many scholars have called for laws to penalize those who engage in these types of behaviors, but several barriers exist, including First Amendment speech protections. However, JoAnne Sweeny, a professor at the University of Louisville Brandeis School of Law, argues that a legal concept known as the “captive audience doctrine”—which takes into account the extent to which a person needs to flee, or is “captivated”— is the most viable theory to justify regulating street and cyber-harassment within the bounds of the First Amendment.

Street and cyber-harassment remain widespread. Women and men who have experienced this sort of harassment have reported that it negatively impacts their lives and makes them feel intimidated. With the knowledge that street and cyber-harassment constitute commonplace problems that significantly impact the lives of victims, why has the law not stepped in?

The U.S. Supreme Court has held that the government possesses a “very limited” ability to restrict speech in traditionally public areas, like streets and sidewalks. The Supreme Court also stated that the offensive nature of the expression is also of no importance, and protected under the First Amendment; the listener or viewer generally bears the burden of averting his or her eyes.

Another hurdle to overcome revolves around the issue that any law limiting sex-based harassment or intimidation would arguably be, according to Sweeny, “a content-based prohibition on speech.” Content-based prohibitions on speech limit the subject matter that a person talks about, and courts examine them with a high degree of scrutiny. The Supreme Court has also held that a restriction on speech based on its emotional impact still establishes a content-based prohibition. Similarly, the Supreme Court has generally opposed restricting hateful or offensive speech unless it instills a fear of physical violence in the listener.

To overcome this hurdle, scholars have suggested various ways to regulate street and cyber-harassment while trying not to violate the First Amendment. One scholar suggests that the courts should not give this type of harassment protection under the First Amendment because it constitutes so-called “fighting words”—words that inflict injury upon utterance and tend to be “personally abusive epithets”—which they have traditionally not protected. Sweeny demonstrates the difficulty of this route by noting that much street harassment is masked behind “compliments” rather than “personally abusive epithets,” cyber-harassment encounters do not happen face-to-face where violence can ensue, and women tend to respond with fear rather than violence and are “socialized to not fight back when provoked.”

Another legal scholar suggests that courts should see street harassment as “low value” speech because it is irrelevant, the speaker does not “impart some knowledge, and the government has a legitimate reason to regulate the speech.” Low value speech typically involves commercial or sexually explicit speech, with street harassment falling under the category of sexually explicit speech. Sweeny argues this approach also faces difficulty because sexually explicit speech requires “much more sexual content” than one would typically encounter with street and cyber-harassment, especially since cyber-harassment can range from innocuous greetings to death threats, neither of which represent overtly sexual behavior.

Instead, Sweeny suggests that the government should regulate street and cyber-harassment under the captive audience doctrine. Although a range of speech falls under the protection of the First Amendment, the Supreme Court has recognized that when the “degree of captivity makes it impractical for the unwilling view or auditor to avoid exposure,” the courts can limit speech.

The question of captivity hinges on “whether the person should have to flee to avoid the speech.” When the audience remains in a location because of need and the speech is difficult to avoid—such as a graduation ceremony or college classroom—the Supreme Court has tended to employ the captive audience doctrine. Public spaces such as sidewalks or parks, however, generally tend to be open and incapable of holding a captive audience.

The method of message delivery is also important, as the Supreme Court has historically shown less tolerance for prohibitions on printed messages than verbal ones, with the common lower court reasoning that “a viewer could easily avert their eyes.” The Supreme Court may also consider the message itself when the speech burdens substantial privacy interests.

In arguing for the use of the captive audience doctrine, Sweeny employs the use of a three-part test outlined by constitutional law scholar Marcy Strauss. The test considers the “justification for applying the doctrine,” “the potential burden on the listener in avoiding the speech,” and “the impact on expression.” Sweeny believes that by using these criteria, she can show that a public street or the Internet “create a captive audience.”

If the public street or Internet do in fact create a captive audience, Sweeny argues that this doctrine could be the key to regulating everyday harassment that commonly happens in plain sight.