Revamping the regulation of legal services might be a first step toward overhauling criminal justice.

Once upon a time, the law forbade parties from waiving the right to a jury in most criminal and civil lawsuits. But populations grew, circumstances changed, and social norms evolved. Laws proliferated to address new problems, such as illicit discrimination, illegal working conditions, environmental damage, and corporate fraud. Procedural rights arose to meet new standards of fairness like the right to counsel for criminal defendants. Caseloads increased dramatically, and the pace of trials slowed.

The legal system needed to adapt—and it did. Parties were permitted to waive the jury. New laws and practices facilitated plea bargaining and civil settlements, making disputes rarely resolved by trials. Many disputes bypassed public courts and came to be resolved instead in private arbitration held sometimes online. Court systems developed technologies that sped up paperwork and allowed detailed monitoring of case processing for each judge. In short, justice systems across the United States became vastly more efficient.

That story of change could be one of salutary innovation. Yet, as Professor Benjamin H. Barton and Judge Stephanos Bibas persuasively describe in their inspired and necessary new book, Rebooting Justice, all is far from well in the nation’s civil and criminal justice systems.

Barton and Bibas make the case that the dramatic transformations of American justice have been insufficient and, in some respects, ill-conceived—sometimes due to unintended consequences. In this brief response to their work, I will focus on their criticisms of and proposals for the criminal justice system, which the authors condemn as even less innovative than the nation’s system of civil justice.

One problem, Barton and Bibas argue, is that the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Gideon v. Wainwright has not lived up to its promise of assuring every criminal defendant effective representation from a skilled lawyer—which is a failing of the political system. Gideon depends on legislatures adequately funding defense lawyers, and it is now clear that many will not.

A familiar, unhelpful response of critics is simply that they ought to. But Barton and Bibas accept the political reality that funding from legislatures is unlikely; instead, they look for realistic—if perhaps second-best—solutions. Two of their key ideas are controversial but meritorious.

First, they would “bow to reality” and cut back Gideon’s scope, so that defendants would no longer have a right to counsel if charged only with an offense punishable by less than six months in jail, the same line that defines the right to a jury trial. That proposal is potentially a big deal: There are many times more petty offenses than serious felonies in U.S. courts.

Second, they target the definition of “unauthorized practice of law,” which gives lawyers a monopoly over providing legal services. And this monopoly is why legal services provision looks so different from the provision of medical services. Regulation of medical practice permits not only doctors, but a range of other skilled, licensed professionals—nurses, nurse-practitioners, physicians’ assistants, and the like—who provide important services at lower cost. But the legal services market has no equivalents.

Certifying skilled nonlawyers to provide certain services ought to bring down prices, putting them within reach of people unable to afford lawyers. On the civil side, for example, paralegals could draft wills, or special advocates could handle bankruptcy or debt collection cases. Criminal courts could introduce new kinds of certifications for “criminal defense advocates,” trained in three semesters’ worth of law school instead of six and at much less cost, who could represent people charged with certain kinds of offenses—perhaps only misdemeanors, perhaps more serious charges as well.

The United Kingdom and Ireland already have taken a step in this direction: Unrepresented parties can have a nonlawyer “McKenzie Friend” assist them in court. Charities have arisen to provide people with experienced McKenzie Friends, and one can even hire a McKenzie Friend for a fee. Scotland allows “lay representatives” to speak in court on behalf of parties and conduct litigation.

Barton and Bibas reframe the paucity of available legal assistance as a problem of regulation rather than public funding, which does not make reform easy. But the different hurdles posed by this regulatory problem might be easier to overcome than funding shortfalls. Instead of lobbying legislatures to fund unpopular programs, the challenge is lawyers’ vested interests in preventing reforms that would open them to competition.

This argument for increasing competition in the legal services market ought to be winnable. The medical profession provides a model, and this kind of reform should bring new buyers into the market—those unable now to hire lawyers but who could retain lower-cost paraprofessionals.

The standard argument against this path is the risk that nonlawyers will provide poor quality services. Given the present dire quality of indigent criminal defense and paucity of civil legal services, lawyers pressing this objection hardly stand on firm ground. A more plausible worry is one that Barton and Bibas’s optimism leads them to overlook.

They foresee a “grand bargain”: With money saved by not providing lawyers for petty criminal charges, and paying just for para-lawyer defense advocates in others, governments can increase defense funding where it is really needed—serious felony cases.

In a better world, that idea makes perfect sense. But legislatures have given us no reason to think that, when they find a way to reduce criminal justice costs, they will divert the savings to other, inadequately funded parts of the system. It seems unlikely that legislatures will be more amenable to increased funding for the defense of serious offenders simply because they can cut funding in other line items of criminal court budgets.

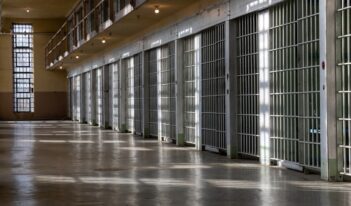

The legal system arguably has been here before. The criminal justice system became immensely more efficient in the last generation through plea bargaining. But where have the savings gone? If any of it stayed in the criminal justice system, rather than going to tax cuts or other public spending, the best answer is that it was shifted to fund more prosecutions and prison space.

This note of pessimism aside, Barton and Bibas have provided an agenda-changing guidebook for future discussions of civil and criminal justice reform. The promise of technological innovations they identify is sorely missing from criminal justice discussions. They have much to say on how changes in court procedures and judges’ roles could improve justice in a system short on lawyers—and how reducing lawyers’ roles can sometimes improve things.

Across a range of settings, they demonstrate how to approach familiar problems from remarkably fresh premises and perspectives. Accessible to general readers and policy makers, Rebooting Justice is also a substantial contribution to legal scholarship. If we, scholars, do our jobs well, it will change the debate for some years to come.

This essay is part of an eight-part series, entitled Revamping the American Justice System.