Federal regulation of domestic and international archaeology comes from a variety of agencies.

“It belongs in a museum!” So says the young Indiana Jones in one of the hit movies from the 1980s after observing the unauthorized excavation of an important artifact.

But the question of who has the right to artifacts found in the United States depends on a number of factors. Government agencies, Native American tribes, and private property owners may all have a claim to artifacts depending on where they were found.

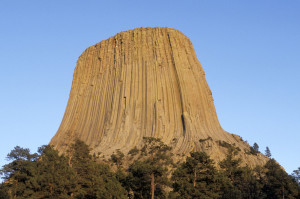

The first and most significant federal law governing archaeology is the Antiquities Act of 1906. This act was the first to establish penalties for illegal excavations, damage, or appropriation of American antiquities. These penalties, however, only apply when the illegal action takes place on land “owned or controlled” by the federal government. The act also authorizes the President to declare historic landmarks as national monuments.

In addition, the Antiquities Act lays out a permitting process for archaeological excavations on government lands. The power to grant a permit lies with the federal agency that has jurisdiction over the lands in question. In most cases, the U.S. Department of the Interior is in control, but for excavations taking place in forest reserves or on military bases, the permitting authority is the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Army, respectively. The act also grants these agencies rulemaking power for historic and archaeological sites within their jurisdictions.

Although the Antiquities Act plays an important role in regulating archeology in the United States, it suffers from weak penalties and lax enforcement. To build on the act and focus further on the protection of archaeological sites, Congress passed the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) in 1979.

The Antiquities Act protects any “object of antiquity” but does not define the term or give examples. ARPA addresses the ambiguity over what is protected by defining the term “archaeological resource” to include “any material remains” of archaeological interest. It also provides numerous examples, such as pottery, weapons, tools, structures, and human remains. ARPA does not consider items under 100 years old, or paleontological items such as fossils, to be “archaeological resources.”

ARPA expands on the Antiquities Act in two other ways. First, it sets forth a more detailed permitting process for archaeological excavations on public lands. Applicants must describe the “time, scope, and location and specific purpose” of their proposed work to the head of the relevant agency. Native American tribes, however, are exempt from these requirements when excavating on their tribal lands.

Second, ARPA expands both the prohibited activities and the penalties laid out in the Antiquities Act. It prohibits trafficking in artifacts excavated illegally under either state or federal law. ARPA also increases the maximum criminal penalty for violations to $10,000 or up to one year in jail, and it imposes even higher penalties for repeat offenders or if the value of the archaeological resources exceeds $500.

ARPA grants rulemaking authority to the secretaries of Interior, Agriculture, and Defense. One of the Interior Department’s major rules provides further details of the permitting process, limiting the recipients of permits to “reputable museums, universities, colleges, or other recognized scientific or educational institutions.” Other regulations outline the process for storing excavated items and arranging exchanges with museums and universities.

The patchwork of laws governing archeological finds in the United States contrasts with the approach taken in other countries where the government asserts that it owns any object excavated within its borders. When it comes to artifacts found in other countries but brought into the United States, the U.S. Department of State’s Cultural Heritage Center oversees customs enforcement under agreements it has reached with these other countries.

The smuggling of antiquities across borders continues to be a serious issue in the art world. Museums in dangerous areas have lost thousands of artifacts to looting and subsequent sales on the black market.

Several groups within the State Department’s Cultural Heritage Center work to counter these threats. The Cultural Property Advisory Committee negotiates with other countries to make bilateral agreements restricting the import and export of antiquities. The Cultural Heritage Coordinating Committee works with diplomats and law enforcement to combat looting and smuggling. The Cultural Antiquities Task Force trains customs officials and law enforcement officers to identify smuggled artifacts and to enforce the laws concerning these items. These various groups also work with other agencies such as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Federal law on antiquities could be changing. In 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Coordinating Oversight, Upgrading and Innovating Technology, and Examiner Reform Act of 2019. The bill focuses on bank security and money laundering but recognizes that archaeological looting has links to financial crimes. It includes a provision that would compel the Secretary of the Treasury to study “the facilitation of money laundering and terror finance through the trade of works of art or antiquities,” a tactic attempted by ISIS and other regimes.

The House bill is currently under consideration in the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs.