Regulations have not decreased cryptocurrency trading within some U.S. and foreign markets.

Cryptocurrencies may have matured beyond their tulip craze stage and emerged as a durable class of investments. Yet their regulatory treatment remains unsettled.

Cryptocurrency proponents argue that new regulation is often inappropriate for these novel assets secured by technical mechanisms. They further claim that regulation of this developing technology would stymie beneficial innovations. These crypto fans also warn that capital will move away from countries adopting stringent requirements and toward those with more laissez-faire regulatory regimes.

Some regulators echo these concerns. For instance, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission’s Valerie Szczepanik, who leads the agency’s cryptocurrencies working group, reportedly warned that overregulation could “chill the market.”

On the other hand, critics of cryptocurrencies point out the frequency of fraud, illegal activity, and regulatory arbitrage in “wild west” cryptocurrency markets. That cryptocurrencies are not tied to governments and do not require buyers and sellers to know each other’s real names to transact makes them attractive to criminals. At the very least, cryptocurrency trading should be subject to a similar array of regulatory obligations—including anti-money-laundering, tax, sanctions compliance, investor and consumer protection measures—that are imposed on other financial activities, argue the critics.

To determine the optimal regulatory regime for cryptocurrencies, policymakers need to know how markets will react to regulatory action. Although that statement is true for the regulation of any economic activity, the stakes are particularly high concerning cryptocurrencies. If traders do not like the regulatory scheme in a particular jurisdiction, they can simply shift their trading activity to an offshore exchange.

Few of the usual switching costs that discourage regulatory arbitrage are present here—moving an individual trader’s activity offshore involves none of the costs and delays of currency conversion, nor does it involve any of the limitations of capital control that inhibit movement of fiat currencies.

In a new research paper, we examine how markets react to different types of regulatory actions over cryptocurrencies. We identify dozens of major government actions—such as the announcement of new rules, novel enforcement actions, and important court decisions—taken in Japan, China, Russia, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These actions concern money-laundering, investor protection, restrictions on cryptocurrencies’ use for payments, and their tax treatment, among other subjects.

We then pair that information with a commercial dataset containing tick-by-tick volume and price information on 56 exchanges worldwide for the two coins with the highest market capitalizations, Bitcoin and Ethereum. We use these data to conduct a series of volume event studies to identify any in-jurisdiction abnormal trading activity in the countries in our study—that is, traders moving their activity either into or out of exchanges located within the affected jurisdictions—immediately following the regulatory action. We also run models concerning global volume and price.

Surprisingly, these event studies yield almost entirely null results. Across all six major countries with substantial trading activity, dozens of major regulatory actions, and hundreds of model specifications, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that regulatory action—virtually any regulatory action—does not affect in-jurisdiction trading activity. Regulatory determinations that crypto-assets are not currencies, bans on their trading or use, and anti-money-laundering and exchange regulation are associated with abnormal declines in global price in some models but not with abnormal changes in global or in-jurisdiction trading volume.

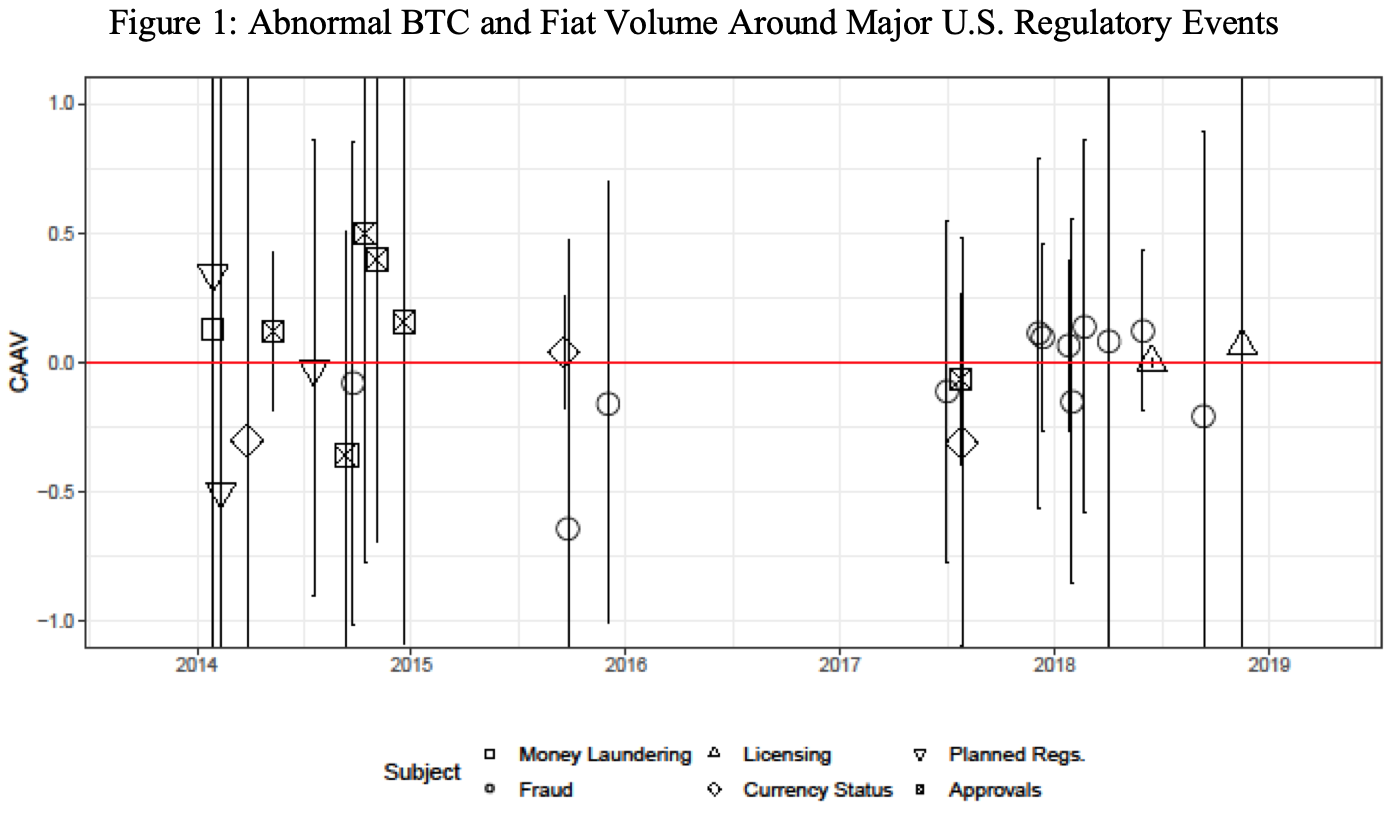

Consider the following timeline of U.S. regulatory events. The figure shows point estimates and 95 percent confidence intervals for cumulative average abnormal volume in U.S.-based Bitcoin and fiat markets around 23 major regulatory events. As the figure shows, the estimates fall far short of statistical significance at conventionally accepted levels. In some cases, the 95 percent confidence intervals extend beyond the figure’s limits, meaning that one cannot reject either the possibility that the regulation in question led to a complete cessation of trading or a greater than 100 percent increase in trading.

These results cast doubt on the concern that regulation will chill economic activity in this sector. We find that “despite the professed antipathy of some cryptocurrency pioneers to regulation, the upsurge in regulatory activity in recent years does not appear to have dampened market activity.” In addition, “we cannot identify any significant shifts in trading activity away from jurisdictions such as the United States where market participants complain about regulatory enforcement and uncertainty, nor toward jurisdictions that have been more welcoming.”

Despite our findings, it is possible that national regulation of cryptocurrencies can still have some effect. One can only draw limited inferences from null results. A few nations have imposed “hard bans” on cryptocurrency trading that impact activity in the country. And concerns about the United States’ classification of tokens as securities has led many initial coin offerings—a tool some cryptocurrency projects use to raise money similar to an initial public offering—to register elsewhere. Exchanges based in the United States, or serving U.S. customers, sometimes avoid listings altogether. But for the cryptocurrencies that dominate trading volumes—Bitcoin and Ethereum—we do not see effects of regulation on in-jurisdiction or global trading volume.

Our null findings should at least cast doubt on the critique that regulation of cryptocurrencies will lead to capital flight. As governments weigh the possibility of increasing regulation on cyber innovations in an effort to serve societal goals, concerns about the ill effects of regulation should not be a first-order consideration.