Scholar argues that right-of-publicity claims can protect individuals from facial recognition companies.

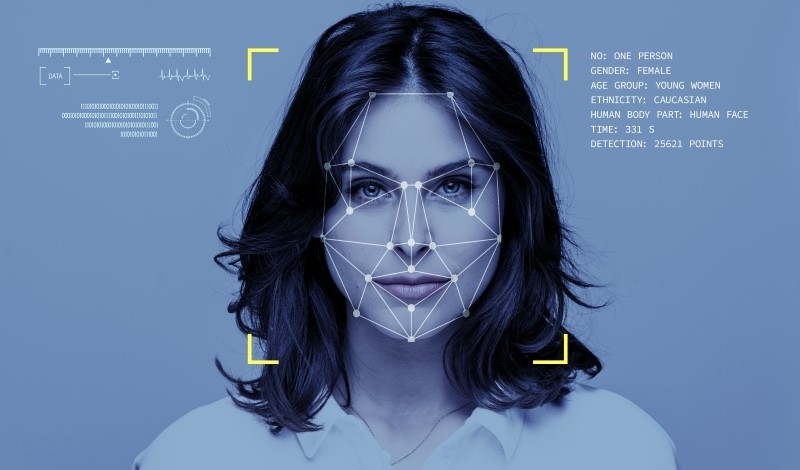

For the machine-learning algorithms that power modern facial recognition technology, practice nearly makes perfect: A recent study found this technology to be over 99.5 percent accurate. This near perfection, however, is only made possible by billions of social media users, whose uploaded images and videos are used without their consent by the companies behind these algorithms.

In a forthcoming article, Jason Schultz, a professor at the New York University School of Law, argues that existing legal frameworks under copyright law and the First Amendment fail to protect individuals from having their personal images appropriated by facial recognition technology companies.

Schultz proposes that social media users instead pursue claims under a rarely used legal doctrine known as the “right of publicity.” That doctrine protects individuals’ rights against having their photos or likenesses exploited for commercial purposes without their consent.

Schultz notes that the right of publicity protects individuals better than copyright law, which focuses only on the economic harm caused by the copier’s use of an original image. By contrast, the right of publicity also recognizes an individual’s loss of dignity, control, and autonomy.

In addition, Schultz explains how courts in the past have been concerned that right-of-publicity claims might interfere with the First Amendment rights of reporters or artists to describe or depict matters of public interest. Schultz emphasizes that these concerns do not apply to facial recognition software companies, because they use people’s images and likenesses “under the veil of corporate secrecy,” rather than to further creative pursuits or promote public affairs.

Scholtz cautions that what it takes to win a right-of-publicity case varies from state to state. Still, he identifies four common elements of the most successful right-of-publicity claims. These elements include (1) a defendant company’s use of the individual’s identity (2) in an appropriative way that is for the company’s commercial benefit (3) in a manner the individual has not consented to and (4) that results in injury to the individual. Schultz contends that all of these elements are met by facial recognition companies’ appropriation of personal images to train machine-learning systems.

As to the first element—use of an individual’s identity—Schultz notes that facial recognition software companies make use of individual’s photos in multiple ways. Not only do these companies display people’s images when the software has identified them, they also use them to train their facial recognition software and improve accuracy.

Schultz also argues that companies can use a person’s identity in violation of the right-of-publicity even without using their actual image. Schultz notes that courts have found right-of-publicity violations in the past when advertisements used identifiable characteristics of celebrities without their consent, such as when a Samsung ad featured a robotic game show host modeled after Wheel of Fortune co-host Vanna White. Because the ad used identifying characteristics unique to White, although it did not use her name or precise image, the court in that case held that Samsung’s use of the robot still violated White’s right-of-publicity.

Schultz contends that a right-of-publicity claim against facial recognition companies could succeed on similar grounds. The companies are using that person’s identity because the machine-learning software has created a “faceprint” of the person’s identifying characteristics. The software then uses this “faceprint” to help make identifications when presented with a previously unseen image of a person.

Schultz explains that the second element of a right-of-publicity claim, the appropriation of an individual’s identity for commercial benefit, can be easily satisfied because the appropriative use of other’s images is at the heart of a facial recognition company’s business. Schultz notes that one company has even stated that its goal is to have multiple photos of every person in the world in its database. As a result, the value of a facial recognition company’s database of images increases the closer it gets to completion of a full set, similar to a collection of trading cards.

With regard to the third element— lack of consent—Schultz explains that facial recognition companies did not always rely on their modern practice of large-scale image appropriation. Instead, Schultz notes that early facial recognition innovators in the 1960s conducted photoshoots, with participants consenting to the subsequent use of their images to develop facial recognition systems. Decades later, the arrival of free search engines holding millions of photos enabled a shift to the modern, consent-free approach.

Finally, Schultz also claims that facial recognition software companies meet the fourth element of a right-of-publicity claim, harm to individuals, because of the emotional trauma and indignity created by individuals’ knowledge of this unpermitted commercial use. Schultz notes that the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that individuals making a right-of-publicity claim can recover for any unfair commercial benefit the defendant has received—even if the complaining individual had never planned on profiting themselves from their likeness. Schultz predicts that this approach could be effective in states such as California, where the right-of-publicity statute prohibits the non-consensual use of a person’s likeness “in any manner, on or in products, merchandise, or goods.”

Ultimately, Schultz argues that facial recognition companies must consider new, consent-based approaches to their image gathering. Successful right-of-publicity claims provide a strong basis for encouraging facial recognition companies to adopt these protections, Schultz concludes.