Howard’s visionary approach to risk assessment made connections across disciplines from public health to climate change.

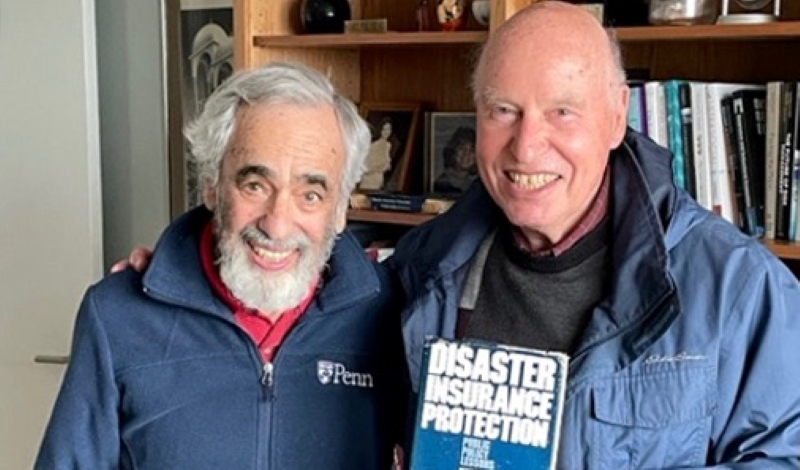

I first met Howard in 1970 at a meeting on natural hazards that was held in Boulder, Colorado, and organized by famed geographer Gilbert White. As the meeting approached, the room buzzed with excitement about the imminent arrival of some guy named Howard. Shortly after the meeting started, Howard burst through the door and immediately joined the discussions, full of ideas delivered enthusiastically in a powerful, deep voice. At the break, he made it a point to greet me warmly and that was the beginning of a scientific collaboration and an equally important friendship that lasted more than 50 years.

We published our first paper together, coauthored with Gilbert White, in 1974. It was a review of work in geography, economics and psychology and was titled “Decision Processes, Rationality, and Adjustment to Natural Hazards.” It covered a lot of ground, blending the then-new psychological work on heuristics and biases with corresponding findings from field observations on flood plains and earthquake zones from studies conducted by White and his students. As we stated in the paper:

It is our belief that the results of many recent laboratory studies merge nicely with the observations of geographers in their field studies, and help provide a more complete understanding of bounded rationality as it impinges upon adjustments to natural hazards.

The last paper Howard and I wrote together was published in 2021, 47 years later. It also addressed behavioral responses to natural disasters—this time from climate change. We called attention to lessons for addressing climate change learned from failures to manage the coronavirus pandemic effectively.

COVID-19 is known to spread exponentially when each infected person infects more than one additional person. The hallmark of exponential growth is that it seems trivial when the numbers of cases are small and it is easiest to manage if we act fast. But exponential growth becomes difficult to contain if we delay. Psychological studies from 1975 showed that most nonscientists did not understand exponential growth and how rapidly it gets out of control. This is what happened with the coronavirus pandemic in its first year, when scientists failed to communicate effectively the dangers posed by the exponential spread of the virus and the U.S.—and most of the world—was slow to act. The lesson from the pandemic and other instances of exponential growth is to act early, before it is too late to stem the explosive growth of the problem. Howard and I pointed out that the same thing was happening with the impacts of global climate change that grow exponentially. Act now, we warned, before it becomes too late.

Howard studied a wide range of risk issues but there were certain persistent themes and issues he never gave up on. He tirelessly worked to make policymakers better able to protect society from natural and technological hazards by helping them understand the ways in which people think about risk and uncertainty. He also recognized that understanding risk behavior must come from systematic, empirical investigations that employ multiple methods of observation and analysis, carried out by multidisciplinary teams. To achieve this multidisciplinary approach, he intentionally included diverse groups of scientists and stakeholders, along with industry and government officials in his work.

In his personal life, Howard was a risk taker, eager to to encourage his friends and colleagues to join him on new paths toward scientific discovery, new ways to collaborate, or even exciting bike rides.

No one but Howard, for example, could have persuaded me to commute to Penn every other week from Oregon to co-teach his decision making course. The commute was crazy, but I loved doing it and basking in Howard’s enthusiasm for engaging bright young students in the exciting world of risk and decision making.

As another example, not long after meeting Howard, I found myself walking alongside him on the hilly streets in San Francisco, knocking on strangers’ doors and asking those brave enough to open them whether or not they had earthquake insurance and why. It was a path I would never have taken myself, but it led to important insights into popular misperceptions about insurance. One common misperception was that most San Francisco residents we interviewed had not thought much about earthquakes. Few were insured against them. Those that were insured had not decided based on any risk or cost calculations—they bought insurance because their friends or neighbors had insurance.

Soon after our door-to-door survey, Howard led a large national survey on insurance decisions. He also advised me on a series of controlled laboratory experiments based on a game where farmers had to decide whether to buy insurance to protect their crops, based on the probability of experiencing a natural disaster and the expected monetary loss. Participants in these laboratory and survey studies did not, in general, worry about low-probability hazards. They preferred to insure against likely events with small losses, rather than against the low probability, high consequence events that insurance is designed to protect us against.

We learned, therefore, that many people think of insurance as an investment. By insuring against smaller, more probable losses, the study participants seemed to view making claims and receiving payments as a necessary return on the premiums paid. Insuring against rare hazards that were less likely to occur seemed to be a waste of money. These findings helped explain consumer disinterest in insuring against catastrophic losses and pointed towards several ways to communicate risk and arouse proper concern about hazards that Howard continued to promote awareness of throughout his long career.

On a more personal note, we all know that Howard had a strong personality with many wonderful qualities. He was a bundle of energy and enthusiasm. He loved to draw his colleagues into working with him. He had no ego. He was interested in others, not himself, and when he talked with them he focused on hearing what they had to say, not telling them about himself. He was friendly and helpful to a fault. When he picked me up at the airport one day, he insisted on carrying my big briefcase for me. “No, Howard,” I said. “I always like to carry it myself.” I then picked up my briefcase and brought it to his car with my other bag. When we pulled into his driveway and opened the trunk of his car, however, there were two briefcases there. Not taking “no” for an answer, Howard had taken someone else’s bag, thinking it was mine. Fortunately, the owner’s name was on it. He was not happy when Howard called and jokingly said “I bet you wondered what happened to your bag.”

Howard Kunreuther worked tirelessly in applying decision science to make the world a safer place. And beyond his important scientific contributions, he brightened the lives of all who were fortunate to know him.

The essay is part of a series celebrating the life and scholarship of Howard Kunreuther, titled “Commemorating Howard Kunreuther.”