Scholar calls for reform of schools’ surveillance systems to protect students’ rights to free speech and privacy.

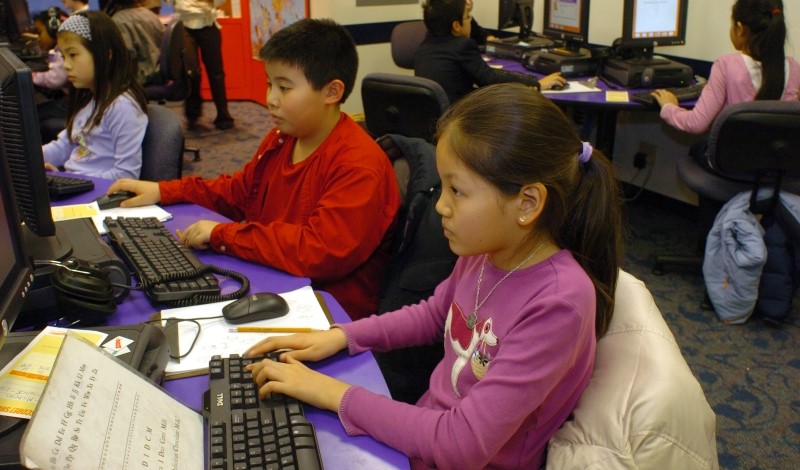

Amid mass school shootings in the United States, the public has called for better measures to ensure students’ safety. Many schools have responded by installing surveillance technologies on campus, such as security cameras, and on school computer systems, such as monitoring and facial recognition software.

But the excessive use of surveillance technologies harms students more than it helps, argues Danielle Keats Citron, a professor at the University of Virginia Law School. In a recent article, she proposes regulatory reforms that would better help public school students feel safe while still allowing for freedom of expression.

With the advent of online monitoring software, educational institutions’ surveillance is no longer limited to school grounds. Schools also employ continuous surveillance systems that track and analyze students’ online activities. For example, Gaggle, a company that provides surveillance services to schools, uses algorithms to identify content that might indicate safety threats on school-provided devices.

Schools employ monitoring software for two purposes: to block students’ access to content that schools find objectionable and to scan students’ online activities—such as emails, chats, search history, and downloaded content—for potential safety threats.

Although Citron recognizes that schools must protect against threats, she argues that students cannot thrive when they know they are on constant watch.

She highlights the profound costs to students’ intimate privacy—the ability to control information concerning one’s own bodies, health, sex, and close relationships. Citron explains that schools must protect students’ intimate privacy because children and adolescents undergo significant personal growth through social interactions and learning—activities that now increasingly take place online. Continuous online monitoring, however, denies students the space they need to explore and learn about themselves, Citron claims.

In addition, Citron argues that school surveillance systems undermine students’ ability to communicate and exchange ideas.

She asserts that these systems harm students as listeners and consumers of information because these systems tend to over-block, filtering websites containing important educational materials, including news sites or sites with information about students’ identity development, such as resources for LGBTQ youth. At the same time, these systems harm students’ ability to express themselves because students tend to censor their activities to avoid attracting suspicion or disciplinary action, Citron explains.

Importantly, Citron notes that marginalized groups disproportionately suffer the negative consequences of school online surveillance. One study revealed that students with learning differences or disabilities are more likely than their peers to suppress their thoughts online because they know they are being monitored. Another report found that surveillance systems have the potential of outing transgender students who may not be open about their identity and are often at the greatest risk of suicide.

Although schools justify their practice for safety reasons, the lack of supporting evidence of the effectiveness of online surveillance systems refutes this justification, Citron argues. Empirical research has shown algorithms cannot reliably detect self-harm, bullying, or threats because algorithms cannot assess the context of online activity adequately. Moreover, reports show that company content moderators lack expertise in social safety or mental health in school settings.

Not only do the surveillance systems fail to protect vulnerable students, they also endanger them, Citron argues. For example, in the wake of Dobbs v. Women’s Health Organization—the U.S. Supreme Court decision that overturned the constitutional right to abortion—students risk discipline and criminalization if their online searches suggest that they have pursued or obtained an abortion in violation of state law. Citron also warns that surveillance systems put transgender students at risk in states that prohibit gender-affirming health care.

Citron observes that the lack of meaningful regulation of school surveillance and student privacy is the root of the problem.

At the federal level, school administrators often cite the Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA), which requires schools receiving internet access at a federally discounted rate to enforce an “internet safety policy” that includes “monitoring the online activities of minors,” as the ground for their surveillance practice. At the state level, although some states introduce student privacy laws, they fail to provide protections against school surveillance of students’ online activities, Citron explains.

In light of how current surveillance systems prevent schools from delivering their educational mission, Citron proposes several paths to reform CIPA. Observing that the Biden Administration’s AI Bill of Rights states that “continuous surveillance and monitoring should not be used in education,” Citron argues that the U.S. Congress should revise CIPA to clarify that the “monitoring” provision does not require tracking students’ online activity.

Alternatively, Citron proposes that Congress could revise CIPA to allow schools receiving federally discounted rates to adopt surveillance technologies only if they provide evidence that the surveillance technologies are effective and designed to minimize harm to students’ privacy.

Knowing that federal discounts are at stake, schools would have strong incentives to get proof from surveillance companies and examine evidence that these systems do not threaten students’ privacy, claims Citron. She argues that this approach would make surveillance companies more responsible for their product design since they would bear the burden to prove the effectiveness and safety of their product.

In addition to reforming CIPA, Citron proposes that state lawmakers should require transparency and oversight over schools’ surveillance projects. Specifically, noting that the contracting process for acquiring surveillance technologies is highly opaque, Citron highlights the importance of requiring schools to provide opportunities for students’ input before signing a contract with a surveillance company. Citron also recommends that state lawmakers require schools to disclose the extent to which students are under monitoring and to outline the measures schools adopt to protect students’ privacy.

Citron concludes by cautioning against seeking an easy solution for what she sees as a hard problem. Students’ mental health, as well as concerns over bullying and violence, are hard problems that schools are desperate to solve. But resorting to continuous student surveillance—effective as it may seem—is not the solution, Citron argues. In a time where rampant false and inaccurate information undermines knowledge and democracy, schools must foster an open environment for students to express themselves so that they can develop critical citizenship skills, Citron urges.